The only really valid argument I have met against my advocacy of natural feeding of cattle with high-quality roughage has been that of labour costs. Though I believe it reasonable to argue that it is better to grow foodstuffs than to buy them in these days of mechanized harvesting, no one has yet mechanized the feeding of silage, hay, and kale, and I am certainly not mechanically-minded enough to devise any machine that can, for instance, cut silage in the heap and fork it into the cows' manger or even spread it in the field. I have often thought it ought to be possible to adapt the manure loader and spreader to get silage out of the heap or pit and spread it in the field; but no one has yet done it that I know of, so for most of us who believe in bulk feeding of roughage the hard labour and its very high cost have continued.

There is no profit in cash gained by replacing bought concentrates only to pay it out on extra labour; the key to profitable milk production is the growing of better winter keep than you can buy, better for both your pocket and your cattle.

Growing-grass is a much more effective food grazed, than eaten after any known system of conservation. Just as milk is more valuable to the calf when it is suckled direct from the dam, grasses and herbs, or any green crop is more valuable eaten fresh from the soil.

I have found, then, that winter grazing of kale and other crops is not only more nutritious and health-giving to the animal, but more economical to the farmer. And pursuing this principle of reducing the greatest cost in winter feeding—labour—I have found that it is possible for the cow to help herself to all the winter food she needs. This applies not only to the grazing of kale but to the feeding of silage and hay (though of the latter I feed only a little, and that only to calves). My cows now help themselves to everything except the bit of dredge corn which they have while being milked.

My winter feeding system combines the self-feeding of kale and silage and also hay when this is used, all at the same time. The cow merely helps herself to either one or two or all of them as she needs them. My policy has for many years been to allow these bulky foods almost ad lib., to the exclusion or severe limitation of concentrates. But until I devised my combination self-feeding system it has involved a tremendous lot of labour—cutting the kale and silage and carrying it to the cows. Now this labour is completely eliminated. Apart from the winter-born calves which are indoors in the winter, work with the cattle amounts to little more than milking them. The long hours of winter feeding have now been reduced to summer proportions. Even when the cows were yarded at night we have racks which hold a week's supply of silage and oat straw so that no food need be carried to the yarded cattle more often than once a week.

Last winter we made and fed 400 tons of silage at a total cost of only 10s. a ton, and ten acres of kale which cost a total of £57 10s. to grow, and £10 to strip graze. Additionally only 5 tons of a dredge corn mixture were used for 'production ration', at a value of £125 total (at market prices), making, with the addition of wages absorbed by milk production, our winter milk costs only 1s. 3d. per gallon, which included also the cost of feeding all young stock, which after all are part of our milk-production costs. I hesitate to quote this figure for fear it is used as a basis for further cutting the price of milk at the next February price review—but it is only by such drastic cost-cutting that we shall survive as food producers, for milk prices are going down whatever we farmers may say or do. And even heavy fertilizer applications, in an attempt to combat falling prices with increased yields, are now in most cases only at great ultimate cost in soil fertility and merely delay the doom!

Such a low cost of milk production is made possible by ruthless slashing of the two major items of cost in milk production—feeding-stuffs and labour. The saving in labour achieved by the self-service system of silage and kale feeding means that in mid-winter, while milk prices are highest, we have continued summer-grass milk-production costs. The farmer's dream of perpetual summer-grass on to which the cows are turned to get their fill, to return to fill the pail, is now all but a practical reality. The main cost of our winter milk production is making the silage in the summer; and thanks to Mr. Rex Patterson's buckrake and our own careful simplification of the system of making high quality silage without frills, even that item of cost is infinitesimal.

Though silage is at last being accepted as an essential part of low-cost milk production, it has been rather because of the lash of incessant rain than the love of silage as a fodder. British weather has driven the dairy farmer to this system of grass conservation reluctantly. If it weren't for the capital outlay he would probably prefer to make dried grass even though the finished product is, in my experience, a much less valuable food.

This reluctance to make silage results from the very involved and cumbersome methods which have been propagated by commercial interests with concrete silos, cutter-blowers, earthscoops, and various acids and chemicals to sell. No wonder most farmers have considered modern silage-making a costly and laborious way of spoiling good grass. For as often as not these involved aids to silage-making have only enabled the farmer to turn lush clover into inedible manure, the smell of which has caused many a fireside threat of a broken home from a wife whose Parfum d'amour has nothing on the old man's silage-scented breeches steaming beside a roaring fire on a frosty evening!

I am not suggesting that good silage cannot be made in tower silos or even expensively excavated pits, with a £1,000 cutter-chopper-pick-up, or cutter-blower-upper. Of course it can; but at what cost, not only in the making—but in the sweat and toil of cutting out of the pit or silo and carting it to the cows. I don't know how you feel; but though I don't mind a good sweat every day in midsummer when I can throw off everything except my hairy chest, I have no enthusiasm for sweating in a silage pit before spreading the silage for the heifers on the hillside in driving sleet.

1. Mowing a herbal ley ready for silage-making. This is the stage of growth, just before flowering of herbs and grasses at which maximum nutritional value per acre is obtained

2. Buck-raking the above pasture for silage

3. Commencing the silage heap

4. Compressing the heap

All the joy goes out of the very best silage when these points are considered; and what you may consider perfect silage, regardless of cost, becomes a failure if it has to be dug out of a pit and carted to the cows. So it is well worth learning how to do the job in the quickest way with a minimum of labour, machinery and unnecessary wear and tear on tyres and gumboots. That means to make it where the cows can eat it, digest it, and spread the fertility from it; while all you have to do is to call them in to be milked and collect the top winter prices at summer costs.

Textbooks, including sections describing how silage should be made, are numerous—but I've yet to read the book saying how it is made by the man who makes it and feeds it cheaply; so I'll attempt to describe my method, if only for the reason that it is the cheapest and easiest method of conserving summer grass and keeping it at its optimum nutritional health-giving and production value that I know.

In making the silage in the field, water to moisten the grass is not always practicable, and molasses, to sweeten it and set in motion desirable ferments, needs water to dilute it. So, for our field self-service silage clamps, we use neither water nor molasses, nor, of course, any of the recommended acids, salts or other activators.

The site of the heap varies from year to year, so there can be no question of concrete sides or base. And though straw bales might be possible, we don't use them because they make no difference to the amount of waste on the sides of the heap. Waste at top and sides depends entirely on the amount of compression in relation to the maturity of the crop. The coarser or more mature the crop that is being used, the greater the amount of compression needed to avoid side and top wastage. It is possible by the open-sided system to have no waste on the sides if it is built at the sides as carefully as the old stack builders built their haystacks; whereas with concrete or straw-bale walls, the silage always shrinks inwards from them, and moist air between wall and silage, which can never dry, causes decomposition.

Siting of the heap depends on the relationship of the kale crop if it is to be self-fed in conjunction with strip-grazed kale; but ideally it should not be in a corner. The site of the silage heap will become the most fertile area of the field, with fertility radiating from it in diminishing quality. This concentration of fertility ought therefore to be on the poorest portion of the field.

The fertility-building value of a self-service silage clamp is one of those free gifts which comes from thoughtful farming. Compare the cost of getting the same fertility into the field if you cut the silage, cart it to the silo or silage pit in or near the farmyard, feed the silage in the buildings or yard, and carry the manure to the field again to be spread by hand or even tractor-driven manure spreader. How much easier to make and feed the silage on the field where it grows, and to allow the cows to provide the labour and motive power to spread their own manure back to the field that provided it.

In climates where it is possible to milk in the field in winter, this system brings to perfection Mr. Hosier's outdoor bale milking system.

So the heap is sited in a spot from which fertility may radiate, provided easy access to the kale is also possible. I have elaborated in Chapter V the possibilities of this arrangement in building fertility on worn-out land, and maintaining it by a three-course rotation, where, on the same field, it is possible to provide entirely for the cows of grass, silage, kale and corn, building up a vast store of fertility as the corn follows the grazed kale and self-feed silage with its aftermath of self-spread dung. (See Chapter V, Self-feeding for the Soil.)

One final point about the site of the silage heap, which may not be thought of until you have, like me, had to shovel a snowdrift off the silage heap while a sleet-laden gale slices the lobes of your ears! Choose a sheltered spot; for neither cows nor cowman will rejoice in self-service silage under a snowdrift or in the face of a fierce nor'easter. One heap we sited on the wrong side of a hedge produced some wonderful silage; yet in the very worst weather the cows preferred empty stomachs and shelter rather than walk round the corner to eat silage in a snowstorm.

In building the heap the important man is the one (or more) on the heap. It is easy enough to sweep the grass up from the swathe with a buckrake and carry it to the site of the heap, dump it and run over it a few times with the tractor. But the man on the heap has to tease out the lumps of green crop which would cause air pockets to form and decay or mould to fill them during the settling of the heap. He it is who decides where each buck-rake load should be dropped in order to keep the material level and evenly compressed, and he should see that the tractors have passed backward and forward over the heap a sufficient number of times between each layer to ensure adequate compression. But above all he must himself trample tightly the extreme sides of the heap, where it is too perilous for the tractor wheels to pass.

Whenever possible he should occupy the outer edge of the heap while standing to tease out the grass, and frequent trampling up and over the outer sides of the heap are necessary to avoid leaving the sides too springy and loose. All the men on the job should join in this march along the sides at the end of each session at the heap, if waste along the outsides of the heap is to be minimized. Keep the top of the heap flat. If the middle is higher during building than the outside it will result in a poorer compaction of the outer edges.

The right time at which to cut the green crop in order to achieve maximum production from the cows which eat the ultimate silage, is a matter of stage of growth of the crop and month of the year. Theoretically, the stage at which the leaf protein is at its highest is the right one at which to cut, whether the month is May or September. This, in my experience, is just a little too soon for best results. At the stage of highest protein the crop has too high a moisture content to make good silage and much of the value of the grass leaches out from the heap. Protein is not the only criterion in maximum milk production, and even in mid-winter is not necessarily the most important to the cow, as many high-yield advocates believe; though I do recognize the importance of getting as much protein as possible from the silage especially in this method of natural feeding. But the juices which are lost in making silage from too young a growth contain vitamins and digestive enzymes, and I believe some of the yet immeasurable essentials of healthy and abundant production. So I find the ideal stage to cut the crop is just after what the experts consider to be the highest protein stage: that is, just before the grasses flower. At this stage the ley may be cut and carried straight to the silage heap—with no need to wilt it to reduce its moisture content, and no need to add water to raise the moisture content (as would be advisable if the crop is left too long).

And as regards the best month of the year to cut for silage: well, if the growth has reached the ideal mowing stage described above in the months of May or June, that is when the best silage can be made. But just as the importance of protein has been over-exaggerated so has the month of the year. A fertile soil will produce nearly as good a silage in August and early September so far as its milk- or beef-yielding capabilities are concerned, though it is probable that the natural growth impulse of springtime in the early-summer silage may have some special health virtues, the value of which we cannot yet measure.

Our first effort at self-feeding silage was from a surface wedge-shaped clamp. This was made in the field where it was intended to winter the cattle, and if it could also be the field in which the silage crop grew so much the better. This meant that for preference our silage was made from an established ley, which would carry cattle in the winter without serious poaching, or from one due to be broken and cropped again in the following spring, so that poaching does not matter. Alternatively, we take an arable silage crop of oats and vetches from a field immediately adjacent to an old pasture or established ley, so that the cows may help themselves to the silage and lie back on to the pasture.

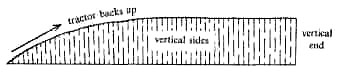

The wedge-shaped clamp was made above ground-level with a sloping ramp up to a vertical end.

The crop is mown in the late evening of the day before it is to be carried—or the early morning of the same day—enough to keep (in our case) two buck-rakes going for the day. The green crop is dropped by the buck-rake on the site chosen for the clamp teased out and levelled by hand labour and the tractor runs over it to compress it. A sloping run-up for the tractor is kept on one end and the other end is built up vertically like the side of a haystack.

This results in a great depth of first-class silage with practically no waste, except at ground-level at the foot of the ramp, and is probably the least wasteful of all systems of silage making.

But the wedge clamp has two serious disadvantages. The first is the danger of a foot slipping and the tractor going back over the end. This happened on a farm near me and the tractor-driver was pinned under the tractor with a broken neck. One of my own men drove over the side by allowing his foot to slip off the clutch when too near the edge; and though he was able to jump to safety the tractor toppled over and went up in flames. The second disadvantage is that with the vertical-ended clamp the area of the self-feeding table available for the cattle is limited—and one end is too high for them to feed from at all.

One of the accepted principles of silage making is that the smaller the area of exposed space in ratio to the cubic capacity of the heap the lower the percentage of waste, so that the higher the heap, the better. But for self-feeding there is a limit to the height of the heap, if the cattle are to be able to help themselves at all times. The settled height of the heap must not be more than the cow can comfortably reach from ground-level. If the height of the heap during making does not exceed 8-10 feet it should settle down to about 6 feet high when finished, which is the limit from which a cow can help herself. And this height-limit means that the heap must either be longer or wider. The greater the length of the heap, the greater the footage of silage from which each cow can eat.

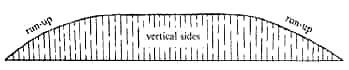

So now we make a shallower, longer mound, still with vertical sides, but a sloping ramp at each end. There is slightly more waste at ground-level each end; but the removal of the cliff-end over which the tractor-driver can dive, and the ability to self-feed from both sides and ends, makes this the most efficient method.

The silage clamp is made above ground-level on the surface of the field, rather like a long stack with vertical sides but with a sloping ramp up either end. With grass, as with oats and vetches, it is mown in the evening of the day before it is to be carried—or the early morning of the same day—cutting enough to keep two buckrakes going for the day. The buckrake sweeps up the green crop from the swathe, carries it to the site chosen for the clamp, and drops it: the tractor runs right over it to compress it. We make the heap not less than two tractor widths—about 15 feet wide which enables us to get best compression. As the heap rises and lengthens, the sloping ends allow the tractor to run with its buckrake of green crop up on end, drop its load, then run down the other end. Each layer is spread by the man on the heap, then the tractor runs backwards and forwards over the heap to compress it. After the first day's work the heap is allowed to heat until it is uncomfortable to the hand, before further material is added; then we work away at it every day.

GROWING THE KALE

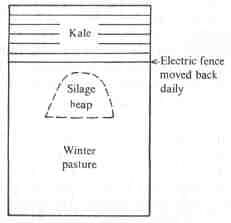

Kale is grown at one end of the pasture upon which the cows are to be wintered, as near as possible to the silage heap from which they are to help themselves, or alternatively in an adjacent field so that the cows may have access to both kale and silage at the same time.

In order to avoid the need to hoe the kale, to get a leafy high-protein crop instead of thick stems and to avoid the fly, we sow the kale in June or July. This also means that adjoining the arable silage heap the kale can occupy the ground from which the oat and vetch crop was cut for silage. This ground should in any case be clean following the weed-smothering effect of the vetches.

Where the kale is taken on an old arable field or a newly broken pasture, we spend as much of the spring and early summer as possible cleaning the land in readiness for the kale. This is done by the repeated use of the disc harrow or rotavator. We then sow the kale—always Thousand-headed which is leafier, more winter-hardy, and of greater feeding value than Marrowstem kale—with the grain drill, at the rate of 5 lb. an acre. This sows in rows approximately 7 in. apart. If we have been able, before sowing, to get the land sufficiently free of weeds, no further work need be done on the kale once it is sown; but if it proves that weeds are still present in numbers or varieties strong enough to compete with the kale, we knock out alternate rows with the 10-in. wide rotary hoe. Normally, however, no work need be done and, with strip grazing to solve the winter-feeding labour costs, kale grown and used in this way becomes a serious competitor with buckrake-built, self-fed silage for the cheapest winter feed for milk production.

Kale and silage fed together—with practically no labour costs—bring the cost of winter milk production just about as low as we are ever likely to get it. The one essential necessary to make these low costs doubly rewarding is to see that the silage is really first-class quality, so that it maintains a high milk yield without the additional cost of concentrates.

THE PROCEDURE FOR SELF-FEEDING

The way the self-feeding is done is to cut a table or ledge all along one side of the silage heap—from which the cows can pull out the silage as they need it. As the cows clear the table of cut silage we cut down a little further so that they don't have to work too hard to pull it out. In this way they can get as much as they want; and a Jersey will eat 100-120 lb. a day on which, if it is good silage, she will produce up to 5 gallons of milk a day in good weather conditions. Larger breeds have been known to eat as much as 125-130 lb. a day. If it is not possible to allow as much as this, then, instead of opening up a flat ledge or table of silage and cutting it loose at the back of the ledge, a sloping face must be left with none of the silage actually cut loose. In this way the cows have to pull out the silage themselves. The steeper the slope on the face the less they are able to pull out; until, with a sheer vertical face, it is impossible for them to get any at all. (See diagrams.)

Cross sections of the silage clamp showing how the quantity of silage a cow can take varies with the angle of the feeding face

During our first year of this system we didn't fence around or across the clamp—and though they occasionally walked up on top of the heap they didn't seem to do much damage. But now we make the heaps long enough to allow the whole herd to feed along one side only, and run the electric fence over the heap just behind the exposed face. This prevents the cows from getting on top of the heap.

5. Self-service silage 1953, when we used the vertical-ended clamp covered with chalk

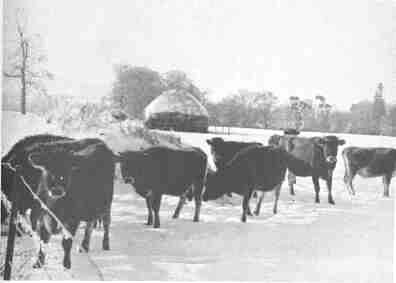

6. The silage heap sometimes has to be shovelled out of a snowdrift—but the Jersey yearlings thrive on it

7. Strip-grazing the kale in field adjoining the silage heap

8. Self-service silage

One disadvantage is the mud that accumulates around the clamp; but bedding down with clean straw solves this problem, though in exceptionally wet weather frequent bedding with straw is needed. There is also a tendency for boss cows to lie down on this straw with bellies full to chew the cud. Bedding a sheltered area of the field a little distance away from the silage heap will encourage them to leave the table when they have finished eating, and make way for the odd heifer or nervous cow that prefers to eat in solitude.

There is room for experiment in portable 'duckboards' or tracks which can be laid alongside the heap to maintain clean conditions underfoot for the cows feeding at the heap. Wire-netting tracks, however strong or fine-meshed, collect mud and trash and aren't really practicable as it is almost impossible to take them up for use elsewhere. Galvanized iron sheets, with slats rivetted across them, are the best temporary floor for this purpose that I have been able to devise. This can, if necessary, be brushed off each day or week, and full cows do not sit down on them and prevent others from feeding. Fixed on small wheels raising them not more than 9-12 inches from ground level, these 'duckboards' become portable with a tractor.

Where the heap can be permanently sited a concrete base for the heap and the cows is the ideal, with drainage or channels into which the dung can be brushed or bulldozed each day.

You may ask: 'What about indigestion—don't they overeat?' Well, there was a tendency for one or two cows to gorge themselves in the first two days of this unlimited silage feeding, but immediately they realized they could help themselves at any time they became reasonable about it. There was also some bullying. The boss cows kept the heifers away. This merely meant that the heifers had to adjust themselves to a rather later breakfast and they came to the heap when the boss cows went away to lie down and chew the cud.

Costs of growing the silage and the kale are as follows:

or £5 15s. an acre.

COST OF KALE FOR STRIP GRAZING £ s. 10 acres cultivation for kale three times rotavated for weed-mulch fallow 40 Kale seed, 5 lb. an acre at 4s. 10 Roll-in at 15s. an acre 7 10 £57 10

or approximately 10s. a ton.

COST OF SILAGE MAKING

(Three men and two tractors and buckrakes make from herbal ley 150 tons weekly.)£ Labour cost 20 Tractor and fuel 15 Proportion of ley costs: 150 tons each year from 12 acres lay costing £16 an acre (see page 35) lasting 4 years equals an acre each year or 48 £73

WINTER MILK COSTS PER GALLON d. Silage and Kale 6.8 Dredge Corn 3.4 Total Food Cost 10.2d. Labour 4.4` Herd Replacements (per gallon) .22 Total cost per gallon

This figure covers total outgoings for winter milk production. A complete costing would require the allocation of interest on capital investment, rent, machinery depreciation, etc. But this analysis is a guide for the purposes of comparison with costings carried out by such centres as Bristol University Economics Department and Wye College. I would suggest that any farmer claiming a cheaper or more efficient system of milk production should join with me in having our winter milk production costed by one of these official and impartial bodies. I am prepared to challenge anyone to produce more milk per acre of land used to feed the cattle, at a lower cost per gallon; and this I believe to be the only true measure of efficient milk production.

Labour costs with this system are of course infinitesmal. The silage face needs cutting about two or three times a week, according to the quantity of silage allowed. The electric fence is moved back on the kale each day—a matter of a few minutes.

With heifers and dry cows, even less frequent cutting of the face of the heap is needed, as they can be left to work rather harder than the cows, pulling out the silage from a much more sheer face.

With 30 cows in milk, one man does all the work of milking and feeding them and all the followers, and has time left to do a few hours' field work during the day. This means that he milks, turns out the cows, washes the sheds and milking machine, feeds the calves with their hand-feed of silage. There is no bucket-feeding to do as they merely suckle nurse cows which come in and out with the milking herd. On the tractor he visits the heifers and dry stock at their silage heap as he goes out for three or four hours' field work each day.

One good man can quite easily milk 50 cows through a milking parlour, do all the feeding by the self-service silage system, and tend naturally suckled calves, and in addition attend to a thousand or two hopper-fed deep-litter hens, filling the hoppers twice a week and collecting the eggs each day.

NEXT