I wonder how many thousands of pounds have been wasted by farmers following 'expert' advice, since the first fertilizer salesman, masquerading as a Ministry of Agriculture advisory officer, inflicted his theoretical knowledge on a farmer?

I often feel glad that I have had the courage to resist most of the advice offered to me, when it has had a recommendation for some commercial by-product of industry wrapped up in it. And, when I have not ignored the advice—and I am ready to listen to advice from any man of practical experience—I have at least passed it through a very fine sieve of sceptical Yorkshire caution. In this way I've garnered a lot of useful knowledge, discovered a lot about the subtle sales-methods of the chemical combines, and saved myself a lot of money which might otherwise have been washed down those tile drains of my fields that were not blocked by my predecessors' losses.

It is generally claimed in orthodox official agricultural circles that it is not possible to establish a good ley without the use at least of phosphatic fertilizers and lime, but preferably plus potassic fertilizers or a 'complete' manure as well. Some experts will admit that a reasonable organic content in the soil might be useful to help in moisture-holding until the ley is established—but by far the greater majority of ley farming experts completely ignore organic matter when advising on the establishment of a good ley. I have searched all the books I know that deal with this subject, and in every case organic manures in the establishment of the ley are mentioned only in a very secondary way.

In every case phosphates are considered absolutely essential, as is lime on acid soils. In all cases, except one, nitrogenous fertilizers are considered important.

In my experience the only essential is organic matter. The use of adequate organic manure, which need not necessarily include animal wastes (though they improve its effectiveness) will, on all soils, ensure the release of all other requirements of the ley. Organic nitrogen, phosphates, potash, even calcium in small but usually adequate quantities, are supplied in the process of decomposition of organic matter.

Synthetic nitrogen is indeed harmful, and in the extent to which it is used the successful establishment of a good clover sward is made more difficult. I am proud to know that my experience in this respect is confirmed by that very honest and well supported ley farming authority, Sir George Stapledon. Writing at the outset of the last war (before the official pressure for the excessive use of nitrogenous fertilizers had begun to rob farmers of their soil fertility, though I am convinced that Sir George was too brave to be intimidated by official government policy), he said in Ley Farming (Faber & Faber): 'All crops respond to nitrogen, but there is a real risk of the soluble nitrogenous manures reacting adversely on sustained soil fertility when applied to land that is out of heart, devoid of humus. . . .

'The risk to be guarded against with nitrogen is that its use will tend to drain the soil of other essential elements and that it will decrease fertility in proportion to its contribution to the bulk of any crop wholly or in major part removed from the farm.

'Thus there is some considerable danger in an over-insistence on top-dressing cereals, and especially wheat, and indeed on an over-insistence on a general use of nitrogen without regard to soil conditions and the wider implications of the manner of soluble nitrogenous fertilizers.'

Sir George Stapledon and I are also in the good company of a greater farmer than either of us, Robert H. Elliot, whose book, Clifton Park System of Farming, in spite of some important limitations and an outdated objection to ryegrass, is still the best basic book on ley farming. In this book he says: 'Landlord's capital mainly consists of soil, and the condition of the soil mainly depends on the amount of humus it contains. About 100 years ago Scottish agricultural capital was on a sound footing, because the system pursued maintained the humus of the soil. It is in an unsound condition now [and this applies to most British and American soil to-day—F. N. T.] because from continuous liming and the use of artificial manures the humus of the soil has immensely declined (hence the numerous complaints of the exhaustion of the soil), and is declining steadily except in those rare cases [very much rarer now!—F. N. T.] where enough farmyard manure can be obtained to keep up the supply of humus.'

'The object of my farming system at Clifton-on-Bowmont is to show how Scottish agriculture may be restored to its originally sound position—not only to replace, but to steadily increase, the humus of the soil, and render the farmer, as he once was, independent of the use of artificial manures. . . . In other words, my farming system is directed to restoring the capital of the landlord to its originally sound and safe position, to lessen the expenditure at present required by the tenant, and place all his crops in a safe position, for contending at once against foreign competition and vicissitudes of climate. . . .'

But there, with Robert Elliot and Sir George Stapledon, alone among ley-farming authors and advocates, insistence on organic matter and the dangers of fertilizers stops. Can anyone imagine any modern chemically-controlled Ministry of Agriculture identifying its objects with those of Robert Elliot, who, let it be admitted, is no opponent of the use of chemicals, for he says 'these may still be used under certain circumstances to a moderate extent'. Yet where is the official adviser who can free himself from commercial ties and, with his Minister's backing, join Robert Elliot in saying 'the object of our advice is to steadily increase the humus of the soil and render the farmer independent of artificial fertilizers'?

Organic matter is the one essential of successful herbal ley establishment and, once established, the herbal ley is itself the best builder of humus, and thus fertility, in the soil, and healthy productivity in the animal.

Ignorance or denial of this fact must be costing the British farmer colossal sums of money in wasted and unnecessary expenditure. For I am quite sure the fact that organic matter is the one and only essential of good ley establishment is not included in the advice of the experts.

The following example of my own experience must be typical of many other farms. Fortunately I had used enough observation in the study and practice of ley farming to know how seriously to take orthodox advice.

Approximately twenty acres of the twenty-eight acres of my field known as Burlons Drove East was seeded down with a herbal ley, in the following manner, in September. The field, being extremely weedy and terribly poor, was summer-fallowed, then sown in July to mustard. It was in such poor heart that the mustard did not make more than about three inches growth before it was disced in during early September. No manures, either organic or inorganic were used. We had no organic manure on the farm (for I was responsible for this seeding before actually taking over the farm on my own, i.e. while I was still at Goosegreen, before moving to Feme, I had the opportunity to crop some of the Feme land and Burlons Drove East was one field thus cropped).

After discing in the small crop of mustard, the herbal ley mixture, as follows, was sown with a seed barrow:

5 lb. S.23 Perennial Ryegrass

5 lb. Commercial Perennial Ryegrass

5 lb. Cocksfoot S.26

2 lb. Chicory

2 lb. Burnett

2 lb. Sheep's Parsley

2 lb. Kidney Vetch

2 lb. S.100 White Clover

1 lb. Alsike

2 lb. American Sweet Clover

2 lb. Lucerne

It was very slow to break ground and went through the winter in a poor thin condition. It was again very slow to start in the spring and it soon became evident that the many weeds, which we hoped the fallow—though a wet one—had destroyed, were gaining control again. I turned the heifers in during April, hoping that they would help to control the weeds and encourage the root development and ultimate establishment of the ingredients of the ley. The weeds grew away from the heifers; they grazed half-heartedly the patches of mainly ryegrass, and to the orthodox eye it was evident that the ley was a failure. In fact when the agricultural committee experts did a survey of the farm in June, that was their verdict.

At that time the ryegrass was about half a crop, there was no clover, a leaf of chicory here and there; but a thick mat of mayweed, thistles and spurrey, all poor-fertility and acidity weeds, covered the whole field. I had a soil-analysis which showed phosphates low, potash normal and pH only 5.5. In other words, on orthodox standards, the ley had failed because I had omitted the orthodox essentials for establishing a pasture —phosphates and lime. It was indeed a pale and sorry sight, and I asked the agricultural committee experts what they advised me to do.

'Well, if you mow what's there, you'll get a bit of hay from the ryegrass to help out your losses and give you a little winter feed. Do that, then plough up the field and give it a summer fallow, ploughing as often as possible through the rest of the summer to try and get rid of the infestation of weeds. Then sow a green crop that can be grazed off with sheep or ploughed in, give a heavy dressing of complete fertilizer with the green crop and re-sow the ley next spring, with sulphate of ammonia to give it a good start.'

'Wouldn't it be robbing an already very poor field to carry this bit of hay off?' I said. 'Maybe,' was the reply, 'but you must use enough fertilizer to make that good.'

In view of the low pH I had already ordered three tons an acre of ground chalk to be spread. What would the additional cost of the committee advice amount to?

£

Plough twenty acres say three times for an

orthodox fallow 80

Seed for greencrop 20

Sowing 10

Complete Fertilizer — £8 an acre 160

Sulphate of Ammonia 40

Lime 60

Re-seeding of ley

Cultivations 30

Herbal ley seed at £8 an acre 160

Sowing 10

Harrowing or rolling in 20

____

£590

Now this must sound, even to orthodox ears, a colossal sum for the establishment of a twenty-acre ley. But it is only fair to say that it must be taken as a somewhat extravagant effort to reclaim a very poor field, and it was assumed no doubt by the advisers that considerable benefit would accrue in the increased production of the ley and subsequent crops, to offset a large proportion of the expenditure on fertilizers. On the other hand, from my point of view, there could be no guarantee of that—and of course it also assumes that there is no cheaper means of getting the ley established and the field into good heart and production.

The fact is, and this is the whole point of this chapter, I turned this apparent failure into one of the best leys in the county, merely by giving it a feed of its own growth, without a penny of expenditure other than wages, fuel and wear and tear on the mowing machine. I did not gather the bit of hay that was growing there—that would have been banditry of my own future from a field so poor. I did not even apply the three tons an acre of ground chalk which was ordered for the field; for at the time chalk was being spread on the rest of the farm, we were mowing this particular field, and I asked the contractor to leave it until later (and the subsequent fine fettle of the ley made me postpone the application indefinitely). I merely mowed the mixture of weeds and ryegrass with the swatheboard off, so that they spread evenly over the ground. What was mown was then left to lie there as a surface mulch. I merely fed back to a very hungry field its own growth, and when there was a second growth through it in August—incidentally when grazing elsewhere was very scarce—I turned all the heifers and dry cattle into it and let them graze it hard. By the end of August it was evident that clovers, chicory and grasses were establishing and spreading rapidly, after the much-needed feed of organic matter and the obvious release of mineral nutrients resulting from the partial decay of the mown weeds and ryegrass.

In September the cattle were moved; and a short growth of clover and chicory, topped off and left to lie again in green high-protein condition, gave a stimulating free kick of nitrogen which clinched the completion of a first-class ley.

With further winter grazing, by March of the following year it was clear that we had a ley that was without superior in Britain. The many visitors, to whom I have not failed to tell the story of the ley that I saved for nothing and kept £600 in my pocket, will confirm my claim to any of the parrots who echo: 'You can't make a good ley without phosphates and lime': who have never tried to make one with adequate organic matter and a mower. And 95 per cent of these visitors who have marvelled at this ley have beeen thoroughly orthodox followers of the poison-powder merchants, including three violently sceptical (but thinking hard when they left my farm) Young Farmers' Clubs, the Agricultural Attache of a great agricultural country who admitted the superiority of my ley but said to a mutual friend later: 'That man's feet make fertility anyhow—he'd farm just as well if he used chemicals—but it might cost him a lot more!'; and many a heavy user of chemicals who wished they had as productive a ley on their farms.

By the time this book is published this ley will be in its third year—but it will still be producing more than any field on similar or better soil conditions in the district. In this, its second year, it supplied over 200 tons of silage, 10 tons of high-protein tripod hay, and most of the grazing for 25 cows, which produced between March and October, with the addition of only 3 tons of dredge corn, £2,800 worth of milk (wholesale prices).

And on analysis, this soil, without addition of a single chemical fertilizer, is no longer phosphate- or calcium-deficient.

On what knowledge or experience did I use the above method of building this ley, instead of taking the expert advice to rip it up and start again at such great cost? For many years I have taken every opportunity, after each grazing of the leys, to top off the surplus grass. Now the orthodox reason for this topping after grazing, quite commonly advised of course, is to stop the seeding stems and encourage a fresh leafy growth. But with the herbal ley, though an important reason for topping off, it is not the most valuable contribution which is made to the subsequent development and production of the ley. For the surplus, after grazing a herbal ley, consists of a considerable proportion of deep-rooting herbs; and these deep-rooting herbs have been down to the subsoil to bring to their stems and leaves a rich supply of minerals, trace-elements and who knows what, which are not available in the top soil to the shallow-rooting ingredients of the orthodox simple mixture of only grasses and clovers.

I soon discovered with the herbal ley, that the benefit resulting from the use of the mower after grazing was obviously far greater than the mere encouragement of leaf growth. It seemed possible that the contribution to soil fertility and the subsequent nutrition of the crop from the feeding-back of this ungrazed surplus was quite considerable. So I decided to develop the practice deliberately as a process of feeding the ley—in other words free fertilizer from the subsoil instead of the usual synthetic top dressing; topping off instead of top dressing. And I found in this way that I could maintain, entirely by utilizing free natural processes, the high production of the ley.

I will explain what happens.

A ley which is grazed mainly by cows, which depend on it almost entirely for the maintenance of their milk output, needs —according to the orthodox soil chemist—phosphates, potash, calcium and nitrogen. It needs—according to me—plant hormones, trace elements, mycelia and fungi, organic acids and a 'stomach-full' of bulky roughage. Additionally I believe optimum growth demands the soil temperature which can only be maintained at an even level by the heat generated from the aerobic bacterial activity which takes place in the presence of decaying organic matter and free air. This means surface organic matter— not ploughed-in organic matter, which cannot do its work below air-level in the soil because of lack of oxygen and atmospheric nitrogen. The optimum temperature for growth and bacterial activity lasts for only a very short period during the summer in soils where the organic content is low, because it is maintained only by external warmth. This explains the wide variations month by month in the soil analyses quoted in Chapter VI on Natural Crop Nutrition. But in a top soil where the level of organic matter continues high—or better still is frequently raised by a surface mulch of short mowings of grasses, clovers and herbs—the variations in the availability of essential nutrients in the top soil is very small, which means that the variation from ideal growing conditions is very small. So that the growing-season of the ley is considerably longer than on the ley managed in the orthodox way: with little or no feeding back of its own growth, but instead frequent bacteria-depressing, temperature-reducing applications of sulphate of ammonia or nitro-chalk. But, the scientist may well ask, what has this to do with the supply of those all-important phosphates? Well, it's the story I've told so often before, of availability. The decay of the mowing mulch releases the organic acids which release the locked-up phosphates. And so, the flow of what I consider an almost unlimited supply of phosphates in most soils (I won't be so dogmatic as to say all soils because I cannot be sure of that, though it may well be), is kept in motion so long as some decaying organic matter is maintained on or near the top soil. I have never known a phosphate problem in a soil where there is ample organic matter; and that need not necessitate the application of compost or farmyard manure, though it may be desirable on seriously overcropped or thin soils. It merely means that some decaying vegetation should be made available on the soil surface—or at deepest in the top three inches—and added to at every reasonably convenient opportunity. All needful phosphates will then be rendered soluble to maintain all the phosphate requirements of the most heavily grazed of pastures. And I have yet to see the soil in which there is insufficient phosphate (albeit insoluble and temporarily unavailable until the acids of decay dissolve it) for this to be done. If any doubter can show me such a soil, I will show him how to grow on it a first-class clover-thick pasture, without an ounce of basic slag, superphosphate, sulphate of ammonia or any other soluble chemical.

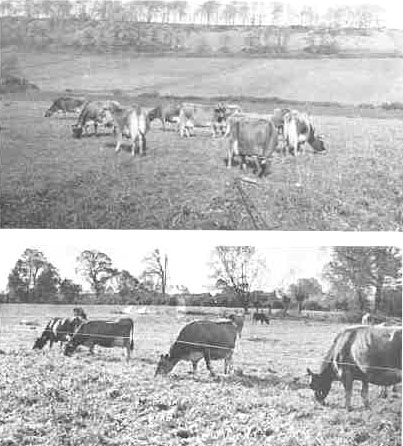

16. Grazing the 'fertility pastures' in electrically-fenced paddocks

17. Waiting to be let into the electrically-fenced paddocks, in the passage between nine paddocks in an eighteen-acre field

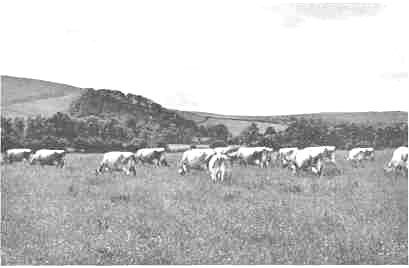

18. The author's herd; heads down to fertility pastures. Note the capacious udders and big bellies to utilize high-quality natural food

19. Some of the herd crossing a recently topped-off paddock

I shall describe in the next chapter another way in which I did this on land which the most reasonable and moderate of expert opinion considered impossible without applying phosphates in some inorganic form.

As far as the potash needs of the ley are concerned, that is never a problem on the fully stocked and properly grazed pasture. Animal dung and urine, in combination with nature's best potash manufacturer, the earthworm, will maintain a potash level in all soils, higher than the maximum needs of any pasture or subsequent arable crop in a sensible rotation. Potash deficiencies are only created by the unbalancing effect of the excessive use of soluble nitrogenous fertilizers. In turn the attempt to correct this artificially-created potash deficiency by the use of inorganic potassic manures, immediately upsets the magnesium balance in the soil, and a worse deficiency for the dairy farmer resulting in the mysterious collapse of his cows shortly after calving. No dairy farmer need worry about potash deficiency; but if he is persuaded to use potassic supers, or sulphate of potash or any other soluble potassic fertilizer, he had better be prepared for the far bigger headache of magnesium deficiency in his cattle.

Faced with either a potash or magnesium deficiency, and quick results are needed, apply seaweed fertilizer which is entirely organic and specially rich in these two elements. If the necessary passage of time required for a natural adjustment— by methods described earlier—can be allowed, no purchased manure of any kind need be used. Incidentally, seaweed fertilizer is the answer to any trace-element deficiency which needs immediate solution. Use it on the ley as a top-dressing in conjunction with a natural seaweed mineral mixture provided ad lib. in troughs for the cows. Synthetic trace-elements or mineral mixtures can be very dangerous, for though a trace-element is essential to life in natural context and infinitesimal proportions it becomes lethal when taken in the smallest synthetic excess. Provided in natural organic form it cannot possibly do any harm. The only really natural form is in the leaves of the deep-rooting ingredients of the herbal ley; or, until the herbal leys are well established by feeding powdered mixture of dried seaweeds and mineral rich herbs. If you use either or both these natural sources of trace-elements you need never fear 'grass staggers' in your cattle or sheep.

NEXT