Chapter 12

'THERE'S ONLY ONE DISEASE

OF ANIMALS . . . .'

I left university with the deep bewilderment about animal diseases, which I imagine is common to all agricultural and veterinary students. The only certain thing about animal diseases seemed to be man's inability to prevent or cure most of them. It was not until I had experienced these diseases in my own herd and started at the beginning in my attempt to eliminate and prevent them, instead of accepting the diseases and treating them as inevitable, that I discovered the root cause of most of them. Until in fact I discovered that there is only one disease of animals and its name is man!

The solution was then simple. If I could get the animals back to a life as nearly as economically practicable to what it was before man perverted them to his own use, and provide them as fully as possible with all the requirements of health available under natural conditions, it was reasonable to assume that health would be restored and maintained.

That in fact has been my experience, and in this section of the book I publish the treatments evolved from this assumption, which have been proved effective when used by farmers themselves on their own cattle in all parts of the world.

But first let me give you some of my experiences which led to the discovery of the simple natural cures for diseases which have hitherto seemed incurable by the involved methods of orthodox veterinary science. I have previously written about the diseases which drained my resources and nearly ruined two herds of cattle; how artificial manures were dispensed with entirely and how manuring entirely by natural means and feeding my cattle mainly on organically grown food and herbs, I restored my herd and my farm to health and abundance from the stage when 75 per cent of my animals were suffering from contagious abortion, sterility, tuberculosis and mastitis.

I spent large sums of money on vaccination and the orthodox veterinary treatment of sterility, and the only result was increasing disease. Some cows aborted their calves as often as three times after being vaccinated, and one after another the cows were declared by the veterinary surgeon to be useless and incapable of further breeding after he had applied a succession of orthodox treatments and failed. He told me that I should never be safe from these diseases until I adopted a system of regular vaccination of all my cattle as they reached the age of six months; I must also fatten and sell the sterile animals and tuberculosis reactors. In spite of pressure, I resisted all this advice, largely because I had not the capital to replace the 'useless' animals which I was advised to dispose of, and partly because I was in any case becoming convinced that we had been tackling disease from the wrong end.

When 25 per cent of my cattle continued normal and healthy lives in the midst of millions of bacteria of all kinds, I became convinced that the much-maligned bacteria were not the primary factor in the cause of disease. After many years' working on that assumption, with the gradual elimination of so-called contagious diseases from my farm, although I am regularly taking diseased animals in for treatment, I have reached the conclusion that bacteria are not only not the main cause of disease, or abnormality in the body, but Nature's chief means of combating it. What we choose to call harmful bacteria are ineffective or inactive except where the abnormal conditions exist to make their work necessary. If we allow them their natural function, to clear up a diseased condition, and do not continue the malpractices which gave rise to the abnormality, leaving the body entirely free of external sustenance until the cleansing work of the bacteria is done, correcting deficiencies only with natural herbs, and then only introducing the patient to natural food grown with organic manuring, good health is the natural outcome.

In experimenting with that disease of the cow's udder, mastitis, I have taken the discharges of cows suffering from it and applied the virulent bacteria to the udders of healthy cows, with no ill effect whatever to the healthy cow. This is a disease which is said to be spread from one cow to another by invasion of the udder with bacilli. Strict germicidal measures are claimed to be the most effective form of prevention and treatment, yet mastitis is costing the farmer more and more every year.

My own cows suffered most severely with this disease when everything to do with them was almost continuously submerged in disinfectant and when I was using all the orthodox treatments. Every farmer knows that his cows will get mastitis under orthodox methods of management and would continue to do so even were they kept under glass cases. The fact is that this disease is merely a catarrhal condition of the udder, brought about by feeding cows for high yields on foods in which the natural elements, vitamins and plant hormones, essential to proper endocrine functioning, either never existed because the food was grown from a soil dying of chemical poisoning or in other ways deficient, or were removed in the process of manufacture.

For many years now my farm has been manured exclusively by natural means, and the animals fed almost exclusively on naturally grown crops.

Kept under this regime, the sterile animals I was advised to have slaughtered have come back to breeding again and formerly useless cattle have been turned into a valuable pedigree herd, the only cost being hard work and a respect for Nature. Had I taken the veterinary surgeon's advice I should have been ruined.

Encouraged by success with my own animals I advertised for other farmers' rejects, particularly those that had been declared incapable of breeding by veterinary surgeons. Regularly, now, I am curing these cows with which orthodox treatment has failed, and only in cases where physiological defects prevent breeding has cure been impossible.

Similarly with tuberculosis, I have reclaimed reactors which would otherwise have been useless. All my work indicates that tuberculosis can permanently be prevented and, in its early stages, cured on food grown in properly managed soil, provided an adequate diet of mineral-rich herbs is given.

Magnesium deficiency, which is a disease arising from the destruction by potassic manures of a trace element in the soil, has been cured at Goosegreen Farm. One animal suffering from this deficiency lay stretched out as though dead for ten days. By a course of warm water enemas, plain water drinks and no foods until the animal was so emaciated that some sustenance was indicated, then introducing diluted molasses and fresh mineral-rich green food, I got the animal back to health. She has since given me several strong calves, 900 gallons of milk in each of two lactations, in spite of her ten-days coma and fast.

Such were the experiences which led me to experiment extensively with herbal treatments for cattle and other animals. In the study of veterinary herbs, I have had much assistance from Juliette de Bairacli Levy (author of Herbal Handbook for Farm and Stable (Faber), Medicinal Herbs—Their Use in Canine Ailments, and The Cure of Canine Distemper and Hard Pad, etc.), whose successes in the use of veterinary herbs are world renowned.

In the following pages I have set out treatments which I have proven time and time again and which are being carried out by farmers themselves at little cost on their own farms. I have dealt only with diseases with which I have had successful results, and which I know can be treated by farmers themselves. Any disease for which I am unable to offer a simple cure, I have omitted from this book, though this does not mean that such diseases are not capable of treatment by natural means.

The following sections are intended to enable cattle breeders to cope with the more common cattle diseases until such time as they are able to get their farms and their herds established in organic methods of management.

All the treatments assume immediate action at the first sign of abnormality in the animal's condition. Any delay is likely to render the treatment less effective. I deal here only with prevention and treatment. The main diseases and their causes are discussed at greater length in Fertility Farming.

ABORTION

Abortion, or premature expulsion of the foetus, is part of the natural elimination of toxins from an overloaded system, and as such is altogether beneficial to the ultimate health of the animal. The loss of the calf should not be regarded as a disaster, but as a life-saver for the dam, which might otherwise become permanently sterile, and incapable of further useful existence on the farm. As it is, with orthodox treatment, she will probably become at least temporarily sterile and if the bad feeding which caused the toxaemia continues, permanent sterility, or other serious toxic condition is almost certain.

But with enlightened management and organic treatment the act of abortion becomes a healing process in the life of the animal whose subsequent health and productive ability will be wonderfully benefited as a result.

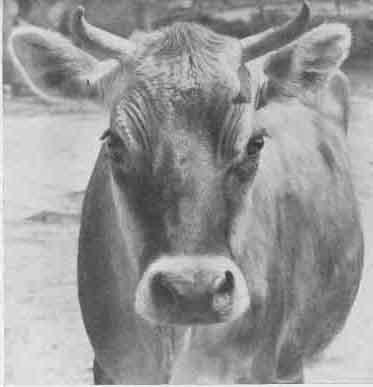

27. Intelligent and dairy-like heads. Polden Summer Storm (Jersey)

28. Intelligent and dairyi-like heads. Pimhill Canty (Ayrshire)

29. Ramsons or Wild Garlic (Allium Ursinum) growing. The most valuable herb in the treatment and prevention of cattle diseases

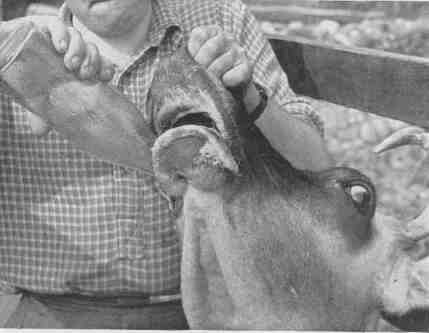

30. Dosing with garlic tablets made from wild garlic

Prevention

Prevention is rarely possible once the obvious symptoms are observed. But provided organic methods are the rule on the farm, it is possible, immediately impending abortion is suspected, to commence treatment which may avert an actual abortion.

As with all toxic conditions, fasting is the immediate necessity. After the first twenty-four hours without food, as it may encourage expulsion of the foetus, it is not possible to give the usual enema, and some form of gentle herbal purgative should be given. The liquid from twelve senna pods soaked overnight in two pints of warm water should be given as a drench on the morning and night of the second day of the fast and repeated on the third day. Alternatively twelve rhubarb-root tablets.

As abortion is basically a catarrhal condition, the best possible cleanser is garlic in some form. If garlic grows wild on the farm, then whole plants should be gathered and fed at the rate of four whole plants daily for two weeks, but commencing with one only on the first day increasing by one each day. If no wild garlic is available, four flaked bulbs of garden garlic may be fed morning and night, similarly commencing with one only the first morning and increasing to a daily ration of four bulbs morning and night. If the cow will not readily take the flaked bulbs, or even the whole garlic plants (which is unlikely as her system will be demanding it), it may be chopped and mixed with a little kale or silage or other appetizing food and a little molasses.

Failing either garlic plant or root, the prepared tablets of whole crushed garlic may be used, giving six tablets in a little water morning and night. The tablets need not dissolve. The water is merely to assist passage of the tablets to the stomach where they will dissolve and achieve digestion slowly, at the same time penetrating the whole system and purifying the unclean places.

During the fast the animal should be kept in and allowed access to ample clean water, which should not be from a tap if possible. Spring, stream or well water is preferable for an animal in normal health, and even more so for a sick animal, as it contains vital elements not present in the dead chlorinated water of the Rural District Council.

The fast should be continued for a week or until signs of impending abortion are passed. At the end of three days if there is no worsening of the condition molasses should be fed, commencing with a pint on the first day increasing by one pint daily up to two pints morning and night. This should be given as a drench diluted in warm water to a consistency which makes it capable of being poured from a bottle. The genuine cane molasses should be used.

If after a week the animal appears to be happy and normal, organically grown green food may be introduced in small quantities, gradually increasing to normal rations of twenty or thirty pounds of good kale, and at the end of the second week a small bran mash—3-4 lb. of bran—may be given with added molasses.

Treatment After Abortion

If, in spite of all preventive efforts, the animal aborts, or if, as so often happens, abortion has taken place without the warnings having been observed, then the only treatment is one that takes advantage of the natural cleansing process which has been commenced, to take the opportunity of getting the animal back to a condition of normal health in which she may enjoy healthy pregnancy in the future.

Immediate action for the cow should be to provide, if possible, the natural stimulus of a calf. If a young calf is available this should be put to suckle the cow at once. This will help to stimulate the normal hormone secretions which have a cleansing effect on the uterus, and which are responsible for milk flow and udder health. The calf should be left with the cow day and night and allowed to suckle at will. If the cow does not take readily to the calf she must be trained by holding three times a day until the calf may be left to help itself. The suckling calf is by far the best treatment for any abnormal calving or udder troubles, as it calls forth the endocrine secretions of the ductless glands—called hormones—which play a major part in the maintenance of health in the organs of reproduction and milk production, and adjust the abnormalities which artificial treatment may have caused.

Then, after a week or two of suckling the treatment for sterility should be followed (see page 134).

ACETONAEMIA

Of recent years, coinciding with the more widespread adoption of forcing methods of feeding cattle for milk, the complaint known as acetonaemia has become much more frequent. There are few high-yielding herds practising modern methods of 'steaming-up' and high protein feeding, which do not have regular cases of this disease.

Acetonaemia is closely related to the high feeding which precedes calving in the attempt to build up a heavy yielding cow, and more especially in the even more common forcing with high protein foods, of a cow which after calving shows heavy milking potentialities and is consequently fed to the very maximum of her production.

I have only had two cases in my own herd; the first we lost through inexperience, in spite of early veterinary treatment of an orthodox nature, the second, which I cured myself. Both were animals which calved down, giving exceptionally high yields of milk, in support of which I was tempted to feed high protein foods to excess. Like most cattle breeders, in those days the higher the potential yield of a cow the higher I tried to force it.

But I have treated a number of cases for other people, and am hearing of an increasing number of cattle which farmers are treating themselves by an early adoption of the simple treatment set out below.

The cow goes off her food and her breath has an odour of acetone, a sweet but sickly smell like peardrops, indicating an attempt on the part of the system to remove excess acetone from the blood stream. The danger period is some two or three weeks after calving, when the results of excessive protein feeding have had an opportunity to take effect.

Prevention

The best prevention, as with milk fever, is a considerable lowering or even a complete withholding of concentrate feeding for two weeks before and after calving. Certainly where a cow is known to have a tendency to acetonaemia or milk fever, protein foods should be reduced to the lowest level for the weeks before and after calving. In the summer when grass growth is lush, the cow should be taken off the best leys and put on to a poor pasture or brought into a loose-box and given hay and bran mashes, until it is seen that she is well over the strain of calving. Then she may gradually be introduced to the production ration which will build up the yield slowly to what may be assumed to be the normal productive capacity of the animal.

Treatment

Acetonaemia is due to an excessive intake of protein and can therefore to some extent be adjusted by the use of a concentrated carbohydrate treatment, but the immediate essential is to encourage natural elimination and the self-correction of the protein unbalance by the animal herself. This can be done by immediate fasting, followed by the feeding of a mineral-rich low-protein gruel made with molasses and powdered treebarks, until such time as the breath once more smells normal, and the animal shows interest in bran mash and a little hay.

During the fast the vitamin value of green food may be obtained without the overstimulating effect of the protein in grass and other green foods, by the use of extracts of grasses and herbs. Leaf plasma tablets are now available which contain the extracts of grasses, nettles, cleavers and other herbs and these may be used to maintain the resistance of the animal during a fast. Four tablets morning and night is the appropriate dose in most cases.

During a fast of longer than two days I have found it necessary to give rectal enemas, for once the intestines are empty and no solid food is being taken by the cow, peristaltic action ceases, and any poisons which are discharged into the intestines are in danger of being reabsorbed if they are not removed by means of the enema. Once solid food is being taken again, and the dung is being passed in a normal consistency, enemas may cease.

The first food may be in the form of small bran mashes and then a little hay. Though in most fasting cases green food is the best introduction to food, in the case of acetonaemia it is well to avoid even the protein of green food until the digestive system has had an opportunity of settling down again. After a few days of bran mashes (five pounds of bran morning and night, and a handful of hay midday) kale or cabbage may be introduced slowly. But any tendency to be disinterested in food should be the sign for a resumption of the fasting and enemas, for this will be a sure sign that the fast was broken before the cow was ready.

ACTINOMYCOSIS OR WOODEN TONGUE

Actinomycosis is the name given to a growth which develops generally in the throat or mouth of the animal, especially the base of the tongue or the side or under portion of the jaw, but which may also be found in other parts of the body. The name actinomycosis derives from the belief that it is caused by a ray fungus and is based on the Greek translation of the words ray fungus.

The real cause of the trouble is a deficiency, particularly of iodine and other trace elements, resulting in the fungus growth, which if not checked may prevent the animal from eating or chewing its cud.

Fortunately the onset of the disease is slow, and it may therefore be eliminated by a slow correction of the deficiencies, in conjunction with a cleansing treatment designed to tone up the animal's system to encourage the quick assimilation of its natural health requirements, and the self absorption of the offending fungal growth.

Prevention

The best prevention is a diet rich in organic minerals and trace elements, obtained by feeding on home-grown foods grown on organically manured soil, and particularly on pastures which contain a high proportion of deep-rooting herbs. A case of actinomycosis is extremely rare on cattle living mainly on the produce of herbal leys; I have never heard of such a case and I doubt if herbal leys of long standing in which the roots of the herbs have had ample opportunity to penetrate to the source of trace elements absent in the topsoil, would ever permit such a disease. There is no doubt that the herbal ley is the best preventive of this as well as many other diseases.

But as an additional safeguard, and in cases where the herbal ley is not established, the feeding of small quantities of seaweed powder or the new seaweed foods will provide all the minerals and trace elements necessary to prevent this and other deficiency diseases.

Treatment

Where the growth has commenced, treatment should first of all aim at allowing the system to adjust itself to the process of eliminating the foreign matter which it has localized at the seat of the growth. This is done by a two-day fast on molasses and water only, with strong doses of garlic. This is then followed by a slow building up of the iodine content of the system by means of a blend of the medicinal seaweeds such as Irish moss, Iceland moss, sea holly and bladder-wrack.

On the first and second days of the fast give one pint only of molasses diluted in warm water to enable it to be poured down the throat of the animal and administered as two drenches morning and night. Six garlic tablets should be added morning and night to the molasses drench.

On the evening of the second day give the same drench but with the addition of two tablespoonfuls of seaweed powder. This should continue to be given morning and night for a further four or five days, or until the growth appears to be diminishing. The molasses may be gradually increased to two pints daily as the fast proceeds, and at the end of a week the animal may be introduced to green food of some kind, slowly increasing it to a normal daily ration for maintenance purposes.

Even when a cure is effected it is wise to continue a daily inclusion of one dessertspoonful of the seaweed powder or the inclusion of 10 per cent of seaweed cubes in the ration, to prevent the recurrence of wooden tongue.

BLOWN, BLOAT, OR HOVEN

Blown, which is also known as bloat or hoven, is the condition in which gases collect in the first stomach of the cow and if not stopped may cause distention of the stomach to the extent of asphyxiation and death.

The trouble is generally at its most prevalent during early spring or summer when the cattle first go to graze lush leys or pastures, and the orthodox explanation is that an excessive ingestation of green food, particularly clover, is the cause. But all curative and preventive measures which have worked on this assumption have so far failed.

Though clover is an important factor it is, I believe, a secondary factor. It is not necessary for the cow to overeat to become blown. The danger is from the production of gases in the stomach and not from gorging. A cow will normally stop eating when her stomach is full. With Blown, gases are produced causing the stomach to distend long before the stomach is full of food. I have investigated internally many animals which have died from this trouble and find that in practically every case there has been some undigested stale concentrate food present in the stomach, and though only a minute quantity, it has been sufficient in combination with the clover, to start fermentation and the rapid production of gases. Most of the blown victims I have examined have been comparatively heavy milkers consuming large quantities of production ration—unnatural food which is not only difficult to digest but lacks the vitamins and minerals which aid digestion. It has been found that the production ration is rarely completely digested until a long spell of spring grazing has provided the necessary digestive tone to enable it to clear up arrears in the stomach. The result is that during the early part of the summer, while undigested food still remains in the system, the risk of blown is great. As the summer advances the risk becomes progressively less, not because the cow eats less clover, or eats less quickly, but because the accumulations of the winter have been disposed of, and nothing remains to set up fermentation. Later in the summer and early in the autumn the danger increases again as the concentrated production, ration is increased and digestion becomes more difficult.

Prevention

If before the cow is put to grass, the stomach is completely emptied of stale food there will be nothing to cause fermentation. Fast the cows for twenty-four hours, especially if there is a known tendency to blowing, and if you can get hold of some charcoal in pieces about the size of a sixpence, or in tablet form, give four to six pieces to each animal. Charcoal is a wonderful thing for absorbing stomach gases and preventing fermentation.

The long-term prevention, which I have found to have a most remarkable effect in eliminating blowing in my own herd, is to see that all the pastures contain a high proportion of herbs and deep-rooting grasses. Late-flowering or broad red clovers should be kept to a minimum, not more than a total of three pounds per acre, where blowing is feared. The herbal ley has a remarkable effect in providing the minerals essential to efficient digestion, and also the coarser grazing which suits the stomach of the cow. Divide the leys into paddocks and graze the cows continuously at the rate of ten or twelve to the acre, rather than 'on and off'.

Treatment

When a cow becomes blown, the immediate treatment after confining her without food, is to give a pint of linseed oil, and if you have them, four charcoal tablets, repeating them every half-hour until the trouble has gone. Keep the animal on the move to assist the movement of gas, and to prevent her from lying down.

Where the distention of the stomach is causing obvious discomfort and appears likely to increase, the stomach should at once be pierced with a trocar and canular, or if this instrument is not available, an ordinary penknife. The point at which to pierce should be the highest point of the distended stomach, midway between the last rib and the hip bone—approximately a hand span from each to the highest point of the distention. Jab the knife or instrument sharply in to its full extent and move it about to ease the passage of gas.

Another means of getting gases to move is to make a twisted rope of hay or straw and push it as far as possible down the back of the cow's mouth, though preventing it from going down her throat. Some of her own dung thrust into the cow's mouth will encourage her to chew in an attempt to be rid of it, and this, in addition to the rope down the mouth, will encourage the escape of gases. Additionally insert a rubber tube, the thin milk tube of a milking machine is ideal, into the anus as far as possible and keep this moving to assist the escape of gas and dung from the rear end.

Once an animal has been blown she must have at least a twenty-four hour fast before she is put to grass again. A large quantity of charcoal in some form will help to clear up remaining gases and fermenting foods during the fast.

CALF SCOUR

The immediate treatment, on the first sign of scour of any kind, is cessation of all food and the dosing with two garlic tablets.

Prevention

Where white scour appears in calves it is generally a result of wrong feeding, usually too high a proportion of protein in the food, or too much milk. Bacteria are quite secondary and are again Nature's means of dealing with dietary abnormality. Prevent by controlling milk intake to 5 or 6 lb. daily from a foster mother.

Treatment

Fast the calf for twenty-four hours on cold water only, and if the scour then appears to have diminished, reintroduce fresh whole milk diluted with equal parts of warm water. If the calf is sucking a cow, reintroduce small feeds of not more than three minutes' duration four times a day, preceded with a bottle of 1-1/2 pints cold water given as a drench, making certain the calf does not receive more than a maximum of six pints of milk during the day. Generally, with a calf that is sucking a cow, a half-gallon is sufficient, though with bucket feeding one gallon a day should be given, when the calf is once more in normal health.

If the scout is still bad after a twenty-four-hour fast, continue the fast a further day, allowing cold water only. If the scour then still persists, gentle warm water enemas of four pints, twice daily, are applied, reintroducing the calf to diluted milk after a maximum of two days' fasting which, with enemas, is sufficient to eliminate the scour completely.

HUSK OR HOOSE AND WORMS

Calves and young animals suffering from a husky cough in the late summer or early autumn may be suspected of Husk or Hoose caused by the lung worm. The eggs of the worm are picked up from the grass of dew or rain-washed pastures, hatch out in the lung and pass into the bronchial tubes from where they are coughed out to the ground again to continue their life cycle.

Prevention

Once the worms have gained a hold in grazing heifers, it is extremely difficult by any treatment, organic or chemical, to eradicate them. Great care should therefore be taken with young stock during late summer and early autumn. All young stock should be kept off permanent pastures or old leys (which carry many more eggs than the young ley) while the grass is wet, for the eggs are found in the dew-drops or raindrops on the blades of grasses and the leaves of clover. Where there is any risk of husk, bring younger cattle in on dewy or rainy nights in late summer and autumn. If the slightest husky cough is suspected, avoid further trouble by housing the group of cattle in which the cough is found, especially if the weather is showery. The only solution to the problem, which is often serious on old grassland, is to plough up the fields and sow them all down to young leys. In conjunction with ground limestone applications, this will get rid of the worms for many years. But even when this is done it is wise to keep the younger stock on the younger pastures.

Treatment

If the cough is taken early and the animals removed from pastures at once, fasting and drenching the system with garlic will eliminate the worms effectively and with considerable benefit to the general health of the animal. But if coughing is at all frequent and has reached the stage of prolonged and frequent bouts of coughing, there is little hope of completely clearing the trouble, and though the animal may live for months or even years, she will always fail to thrive and may eventually die from parasitic pneumonia. In early cases, confine the animal in a clean warm building, with ample ventilation, and withhold food of any kind. Even water should be omitted, if convenient. A heavy dose of garlic should be given—at least 15 tablets in a little water, and the garlic should be repeated every four hours during the fast which should last two days. At the end of the fast give the animal dry food only, hay and home-grown meal and 8 garlic tablets daily for a week, or until the cough seems to have gone. The aim is to keep the system thoroughly loaded with garlic, which not only eliminates the worms or their larvae, but also clears out the mucus in which they live.

Generous feeding should follow the fast in order to build up the natural resistance to parasitic attack in the future, and to throw off any worms which may still remain.

WORMS

For intestinal worms, the treatment is the same as for Husk except that green food and bran mashes should replace dry food for a week following the fast.

JOHNE'S DISEASE

The widespread incidence of Johne's disease among cattle coincided with the practice of feeding the calf on milk substitute, the general use of manufactured cattle foods of all kinds and the consequent deteriorating digestion of the animal. Far from being caused by a mysterious virus, (which is the usual explanation of any trouble for which there is no obvious cause), and for which there is no orthodox cure, Johne's disease really starts at calfhood with a weakening of the whole digestive system. Later in life, no doubt after a year or two of concentrated foods the cow suffers from incompletely digested food remaining in the intestines and setting up fermentation. If allowed to continue, this breaks down the mucous membrane of the intestines, and eventually the walls of the intestine. The corrugations which form on the walls of the intestine are an attempt on the part of the system naturally to localize the toxic wastes. Incomplete digestion causes, in the early stages an excessive appetite, but the continued intake of food to be added to the fermenting wastes already present, merely aggravates the condition and as the fermentation develops and inflammation of the mucous membrane sets in, loss of appetite follows with ultimate emaciation and death.

Prevention

The simple prevention of Johne's disease is a diet of natural foods, and if there is no alternative to the limited feeding of concentrated prepared foods then occasional fasting is necessary to enable the system to eliminate the residues of unnatural food which are never completely digested or absorbed by the body.

It is essential that the diet should contain a high proportion of fresh organically grown foods rich in vitamins, trace elements, and plant hormones, all of which are essential to complete digestion. It is probably the absence of these prerequisites of good digestion from the food ingested, rather than the concentrated nature of the manufactured food itself, which is the real cause of the trouble. For it is not until the animal has had many months of unnatural food that she starts to scour—the first sign that the digestion is impaired. The feeding of food which does not supply the vital elements necessary to healthy digestion and assimilation and which in any case is difficult to digest by the bovine stomach designed for bulky foods, has a cumulative effect which the animal system eventually fails to cope with and the cow herself at last refuses food, when however, it is too late.

A herd which is naturally reared from birth—with calves suckled on cows an essential part of that rearing, (for nothing impairs the digestion more effectively than gruels and calf cake at an early age, though it may not become apparent until cowhood)— which is fed on organically grown bulky food with a high proportion of fresh grass or its nearest winter equivalent silage, tripodded hay, and kale, supplemented where necessary with herbs and organic minerals such as seaweed in some form, will never suffer from Johne's disease. But even in a herd so managed, any animal showing the first sign of digestive trouble, with scouring, should be fasted at once for at least twenty-four hours, or until normal again. This will eliminate any possibility of an accumulation of the causes of intestinal fermentation or inflammation.

Treatment

If for any reason Johne's disease has developed—provided the mucous membrane of the intestine is still sound and there is no sign of blood in the dung, it is possible to save the animal by keeping the whole alimentary tract free of food until it is quite clear of fermenting wastes. This may mean fasting the animal for one or two weeks, in which case daily enemas should be given with dosage of garlic, 6 tablets morning and night. After a week of complete fasting the animal may be given a gruel of powdered fenugreek seed with the addition of powdered treebarks available from veterinary herbal firms.

A two-pint gruel may be prepared by using a dessertspoonful of powdered fenugreek seed and a dessertspoonful of a powdered tree-barks blend (slippery American (red) elm and English elm barks), stirred into a smooth paste with an equal quantity of cane molasses, diluted with warm water. The powdered treebarks are available from herbalists. If a blend is not available, pure slippery elm bark will do—not slippery elm food, which is often diluted with flour.

This will form a soothing jelly-like gruel which will act as an internal poultice and assist the healing of the alimentary tract and at the same time provide an easily digested nutritive food.

The animal will live for weeks on this gruel—but after a week some solid green food may be tried if the dung appears to be of normal consistency. If the dung from this solid food continues to be passed in normal condition the animal may be assumed to be cured and the quantity of green food then gradually increased to normal. If diarrhoea again results then the fast on gruel should be continued for a further week—and so on until the animal is found to be able to deal with solid food.

The garlic should be continued daily indefinitely as an assistance to the elimination of mucus and the general purification of the blood stream. And a mineral rich diet from herbal leys and/or the addition to the diet of seaweed powder, is essential to the continued avoidance of Johne's disease.

JOINT-ILL

Joint-ill is not so frequent among calves as among foals. But it is a disease of calves, in which abscesses or thickenings form at the joints. Because of the frequent occurrence of an abscess at the navel or umbilicus, preceding or coinciding with the thickening of a joint of the leg or shoulder, it is believed that this disease is caused by germs which enter the tody through the navel of the young animal at or shortly after the birth. Having had experience of joint-ill following the strictest possible precautions against infection through the navel, on farms where the calf is born in the cleanest possible conditions, and the navel disinfected immediately after birth, I do not accept this explanation as the primary cause. In my experience the disease is the result of a toxic condition in the dam, probably due to some deficiency in her feeding, the effects of which the calf's system attempts immediately to eliminate at birth. The calf thus develops an accumulation of pus at the navel, the only open point of discharge, and if elimination at this point fails, an accumulation at the joints follows. This joint swelling often occurs in adult animals suffering from similar toxic accumulations and is a common means employed by the system to localize poisons with a view to their ultimate elimination.

If the animal can be fasted immediately there is any sign of an abscess and supplied with the deficiency a speedy reduction of the swelling takes place. Usually, however, the swelling is not noticed until it has gained a considerable growth and with the very young animal it is then not possible to fast long enough to effect a speedy cure.

Prevention

I have found that this trouble responds to treatment with iodine in some form. This indicates that iodine deficiency is one of the causes. The most obvious preventative then is to see that the dam has an adequate supply of iodine in the diet during pregnancy. This is best supplied by the richest known source of organic iodine, seaweed, fed in powder or cube form, or as a long-term preventative, via the soil in the form of a top dressing of raw seaweed or compost made from or including seaweed.

Treatment

Immediately there is any sign of abnormality at the navel or any swelling at the joints of the knee, hocks, hips or shoulders, fast the calf on honey and water (a teaspoonful of honey in a pint of water three times a day). The fast should last for twenty-four hours if the trouble is caught at its commencement, or for two days if there is any considerable swelling. When milk is resumed continue with honey and water with addition of one teaspoonful seaweed powder morning and night.

During treatment the calf should have 2 garlic tablets morning and night and, if there is no evidence of normal dunging, 4 tablets of rhubarb root each night until the dung is normal. Alternatively, as an aid to intestinal movement, the liquid from the soaking for twelve hours, of 4 senna pods in a cupful of water, should be given as a drench.

MASTITIS

Mastitis is a catarrhal discharge thrown off by the cow's system at the point of greatest strain, and is the result of systemic toxaemia brought on by one of two factors. Either a diet which is not equal in its contents of the natural vitamins and plant hormones (which are the pre-requisites of the natural cleansing processes of healthy body secretions) to the output demands upon the cow; so the process breaks down; toxic catarrh replaces the natural hormone secretions of the mucous membrane of the udder. Or an excess of unnatural feeding causes the accumulation of toxic matter in various parts of the body which must be discharged in various ways, by mastitis, big knee, influenza or pneumonia, leucorrhoea (whites) or abortion, all of which result in a catarrhal discharge from one or other part of the body. In either case, if the excessive or inadequate feeding is continued, the trouble becomes chronic.

Prevention

If a period of fasting with frequent stripping and other efforts to eliminate mucus until the discharge ceases, is followed by a completely natural diet, devoid of artificial foods, and composed primarily of green foods, roots, hay, straw and silage, the trouble will clear itself, and in the process the cow will become healthier in every other respect. She may not give quite so much milk each lactation, but at least she will have many more healthy lactations, and any progeny she may bear will be one step nearer perfect health than she was herself.

Mechanical injury is, of course, another matter which cannot be expected to respond to natural treatment quite so quickly as mastitis caused by systemic toxaemia. Mastitis resulting from mechanical injury is usually the aftermath of bad machine milking or a blow from another cow. This is how the milking machine is wrongly blamed for udder trouble. In my experience, a milking machine cannot cause, or spread, udder trouble when properly used.

The fallacy that the machine spreads the disease may be discounted in the properly managed herd, for as I have previously stated, a healthy udder will not contract mastitis even when in contact with virulent bacteria. The bacteria cannot develop in the udder unless there is catarrhal material to be consumed.

Treatment

On first signs of abnormality in the milk or udder, stop all food and allow water only, until the milk becomes normal. Give a strong dose of garlic in some form and repeat it morning and night for a week or more. Two whole garlic plants chopped up and made into a ball with a little molasses and bran or 4 tablets of garlic fortified with the herb fenugreek. Milk out the affected quarter as often as possible, at least four times daily, but hourly if possible, or allow a calf to suckle it, making sure that it draws the affected quarter.

If there is any sign of inflammation in the udder apply alternate hot and cold fomentations, with massage, three times daily to the affected quarter or quarters until the inflammation goes, and during treatment finish off with a cold-water hose turned on to the udder and over the loins, for ten minutes, thoroughly soaking the region of the pelvis and udder. This stimulates a quick exchange of blood and speeds natural purification.

Work on the assumption that the mastitis is a catarrhal discharge resulting either from overfeeding, or feeding on a diet which is deficient in the vitamins and plant hormones essential to milk production. Fast the animal to give the body an opportunity to eliminate this catarrhal discharge naturally and assist this elimination by milking out the discharge as often as possible.

Continue the fast for as long as three days, giving a daily enema after the first day—after which if the milk is still not normal, a pint of cane molasses may be given diluted in warm water as a drench—divided into three doses daily for a further two days, but still without food. Continue the purifying garlic morning and night.

If the mastitis is caught soon enough such a long fast should not be necessary. Twenty-four hours is generally long enough if the animal has no food whatsoever.

When discharge has ceased, resume feeding with green food only— green food grown on composted land without any chemical manures. Continue feeding for a further week entirely on green food, without any concentrated food. She may then gradually be brought back to production ration—but not to excess.

The orthodox treatment is to suppress the discharge by means of penicillin or sulphonamides but unless the catarrh which causes the trouble is eliminated it will recur.

In addition to the feeding of natural food, rich in herbs providing the necessary minerals and plant hormones, a weekly dose of garlic, 4 whole plants or 6 tablets and a daily dessertspoonful of seaweed powder are excellent preventive measures.

31. Natural treatment for cattle diseases. The garlic douche and enema should be given when an animal is fasting

32. Giving a rectal enema

MILK FEVER

Milk fever, though not strictly a fever, for there is rarely a high temperature, is commonly known as 'dropping after calving', though its technical name is parturient apoplexy. The symptoms are a restlessness, at any time from a few hours after calving up to four weeks or so after calving, in which the cow starts by raising first one hind leg and then the other in a paddling fashion and eventually collapses. She lies down and repeatedly turns her head back to her ribs. As the condition develops she will throw her head and the whole of her body back to the ground and may reach the stage of a coma, when if not attended to she will die.

Milk fever, perhaps more than any other disease, is the obvious result of over-exploitation of the cow. It is rarely found in poor milking cows and beef cattle, being confined almost entirely to dairy breeds and the heavier milking animals of those breeds. Further support of this theory is the fact that heifers never succumb to milk fever, and it is not until the cow has suffered two or three lactations of exploitation that she suffers. The third calving is usually the earliest time for milk fever.

It is caused by the strain on the system of the double stimulus of parturition and high protein feeding on the flow of milk. With a heavy milking cow the stimulus of calving on the flow of milk is already great. To add the additional stimulus of high feeding is too much for the cow, the flush of milk is so sudden and drains the blood stream and the ductless glands of all the requirements of milk production—various minerals, calcium and hormones—that the rest of the body almost ceases to function, and the cow collapses.

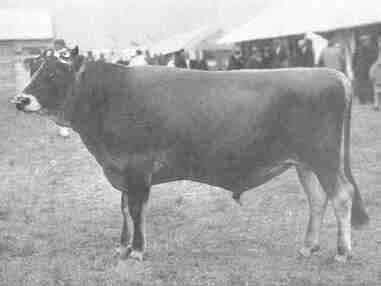

33. The Jersey bull

34. The Jersey cow

Prevention

Knowing that the cause is over-stimulation of the milk secretion, the prevention is simple and obvious—to reduce in all cases, and to cut out completely in cows known to have a tendency to milk fever, all foods likely to stimulate the flow of milk two weeks before calving. Feed in the ration during pregnancy a mineral-rich supplement which will build up the mineral reserves of the blood stream and the supply of hormones and in general bring the whole metabolism of the body to a high pitch of efficiency. The danger in high feeding is not so much the overfeeding of the animal, as the inefficiency of the cow's metabolism to cope with the diet. A diet rich in minerals and plant hormones is known to be beneficial to the animal metabolism. This may be achieved by the use of seaweed on the land and in the diet. Channel Island cattle are particularly prone to milk fever away from the Channel Islands, and the obvious explanation is the change from a soil heavily dressed with seaweed from which the cow derives the requirements of a highly efficient metabolism (this I think also explains the higher fat and solids content of milk in the Channel Islands) to soils which never get even as much as a smell of the sea, and in most cases precious little organic matter of any kind.

In addition to the use of seaweed wherever possible, organic manuring and the use of deep-rooting herbs in the pastures will contribute greatly to improved metabolism and the prevention of milk fever.

Treatment

Having fed the cow to the point of milk fever, or having bought one just after someone else has 'steamed-up' it, and she goes down with milk fever, it is too late to be certain that seaweed powder will act quickly enough, though there is no doubt it will help. So milk out the udder and inflate it with the apparatus which you should have had in readiness beforehand, and which is available from veterinary equipment suppliers.

The equipment consists of a teat syphon and filter chamber which filters the air which is blown through it into each quarter through the teat, after the udder has been thoroughly washed and milked out. The effect of this inflation of the udder is to prevent any further flow of milk into the udder and stop the drain of hormones and minerals from the blood stream to the udder. This enables the cow's system to adjust itself slowly to the demands which heavy milk production are putting upon it. The cow should also have a dose of two table-spoonfuls of seaweed powder in molasses and warm water (two table-spoonfuls of molasses) every three hours until she is up and walking about again. Into this mixture should be added four leaf-plasma tablets each time, to supply the vital tonic elements of grasses and herbs without the protein stimulant.

It is essential that the cow is kept propped up in the normal sitting position with bales of straw. On no account allow her to stretch out on her side. Then, if she appears slowly to be improving don't rush her to get up. She may, and quite understandably too, need a few hours' rest.

GRASS TETANY

Grass tetany is a more recent and more acute form of milk fever, and though it has been given a new name it has all the same symptoms and causes as milk fever, i.e. over-stimulation of milk secretion by the excessive protein of a rich clover ley, especially on top of the use of high protein cattle cake. But because it is far quicker in its action and results in death often before there has been an opportunity to treat the cow, it has been regarded as a separate disease. It may, however, be prevented in exactly the same way as I have advised for milk fever, and the treatment is the same should you be fortunate enough to catch the cow while she is still alive.

RED-WATER OR MURRAIN

Red-water is the result of tick infestation, especially on marshy land. The best prevention is to plough and reseed following a dressing of three tons to the acre of ground limestone. Where this is not practicable, tick attacks on cows may be kept to the minimum by grazing sheep on the same land. The tick prefers sheep which are themselves immune from the poison resulting from the tick bites.

Treatment

Follow exactly the same treatment as for Husk or Hoose, but with double the first dose of garlic and the addition of a dose of 2 lb. of common salt at the outset given in a treebarks powder gruel (two dessertspoonfuls of treebark blend, two dessertspoonfuls of molasses and warm water). After two hours give 2 pints of linseed oil with 2 oz. of turpentine. Continue 8 garlic tablets daily and don't press the animal to take food too soon.

RHEUMATISM

All food is withheld from the animal, and a fast continued for a week, or until the lameness has disappeared—whichever is the shorter. During the fast nothing whatever is given, except water, and the animal is confined in a house without straw bedding. Sawdust, peat moss or old sacks are used for bedding. Rectal enemas are given daily during the fast, using a bucketful of warm water each time. Garlic is given morning and night at the rate of 4 tablets or 2 whole plants.

The playing of cold water on to the affected part, for ten minutes morning and night, during the treatment will help to speed the cure by stimulating the blood circulation at the point of toxic accumulation, thereby assisting the process of purification.

At the end of the fast the animal is introduced gradually to compost-grown green food only, for a week, unless the lameness appears by that time to be cured, in which case a little hay is also introduced. Thereafter, gradually bring the cow back on to her normal diet, having regard to the fact that, the feeding of manufactured concentrates is particularly to be avoided. The best production ration is made up of three parts (by weight) of ground oats to one part linseed. All cereals, as with green food, organically grown; it is advisable always when feeding sick animals, to choose foods grown on soil which has received good dressings of properly made compost.

Should the condition not be completely cured by one treatment, or in the event of it recurring at a later date, repeat this treatment periodically until the animal is completely healthy, ensuring in the intervals between treatments that the animal has an adequate supply of organically grown bulky food. Feeding which includes a wide variety of herbs, especially parsley and celery which have special properties in the prevention and treatment of rheumatism. Dried powdered parsley and celery may also be given during the fasting treatment by placing one dessertspoonful of each (preferably at different times) on the back of the animal's tongue—or in water as a drench. The regular use of garlic in some form is essential if there is any tendency to rheumatism or any catarrhal condition.

RINGWORM, ECZEMA, MANGE, AND

OTHER SKIN DISEASES

I have grouped skin troubles, whether parasitic or merely the result of systemic elimination, because the treatment is almost identical. All skin troubles arise from deficiency feeding initially and may be tackled by a combination of fasting, improved nutrition, and external herbal treatment.

With any skin trouble fast the animal first of all for two days, unless it is very young when one day fast and one day on light milk or green food diet will suffice, and give a gentle laxative—either the liquid from 12 senna pods soaked in a pint of water, or 8 rhubarb tablets each night for three nights.

Then put the animal on to a diet of green food only—whatever quantity is normal for the age of the animal. With ringworm dress the parts with veterinary iodine initially and then follow with daily dressing of a herbal healing cream which I have evolved from the most effective cleansing and healing herbs, garlic, marshmallow, comfrey and chickweed. It is not easy to make up your own cream but I have arranged for my formula, together with the blended herbs which are suggested in other treatments, to be made generally available from reliable sources.

For skin troubles other than ringworm, fasting and a change to entirely green food diet as advised above, but no iodine should be used. The affected parts should be bathed in warm water, then daily dressed with the herbal healing cream, until the trouble has nearly subsided when it should be allowed to dry up and be left without further attention. Fresh air and sunshine should be allowed to the maximum available.

It is most important that the bulk of the diet should consist of fresh whole, and as far as possible green, food in order to maintain a healthy skin.

TEAT SORES OR COWPOX

Cows often develop sore teats during milking, particularly if their udders are being washed regularly with disinfectant. Cow-pox is also a troublesome complaint which tends to spread if not stopped.

Prevention

Give up the use of disinfectant, for it will not prevent mastitis (see my explanation of the real causes of mastitis under that heading in this book) and then proceed to apply the following healing treatment.

Treatment

Wash the wound in warm water and salt, and dry thoroughly. Dress the wound or sore with the herbal healing cream advised for skin troubles, then wrap the sore with waterproof adhesive tape (which may be obtained at any chemist's shop). Don't disturb the bandage until a clean piece of tape appears to be needed when the sore may again be dabbed clean with a dry cloth dressed with the healing cream and wrapped with adhesive tape again. Always see that the tape completely covers the sore during milking for the less the place is disturbed or rubbed once it has been dressed, and the longer it can be kept dry (except for the healing cream) the quicker it will clear up.

STERILITY

The real causes of sterility start at birth when both cow and calf are deprived of the natural stimulus essential to the health of the reproductive organs, which suckling provides.

Prevention

Rear all calves naturally on foster mothers or their own dams (one quarter or less for calf—the rest for you) and give abundance of natural mineral-rich food throughout the productive life. Avoid over-exploitation.

Treatment

To commence the treatment, the affected animal is confined wih-t out food of any kind for a period of at least seven days—for the first and second days also deprive it of water. If it appears to be in good condition at the end of seven days, the fast is extended for a further week, allowing a limited amount of water, i.e. about one bucketful morning and night. Rectal enemas and vaginal douches are given once daily during the fast, using at least four gallons of water each time, for each enema, rectal and vaginal. It is preferable to continue the enema each time until the water discharged is clear. Into the last half-gallon of water each time dissolve four crushed garlic tablets and if possible retain in the intestine and uterus respectively, as long as the cow will naturally hold the water.

Give a dose of garlic, the whole of two chopped garlic plants, twice daily, or 6 tablets of prepared garlic morning and night during the fast. This is given in a drench of the liquid from a bucketful of raspberry leaves or 2 to 3 oz. of dried, cut raspberry leaves, soaked or boiled in hot water. The garlic helps to eliminate the toxins which cause sterility and the raspberry leaf tea has a powerful tonic effect on the uterus and organs of reproduction.

When the fast is ended the animal is reintroduced to compost-grown green food only; such as oats and vetches, kale, or any other composted green crop available, or failing this, to controlled grazing of pasture which have received a dressing of compost during the last two years. A small field, with not too much growth, is suitable for this, and if the growth is not too lush the cattle may be turned on to it continuously.

The animal is continued on compost-grown green food only, for a period of five weeks, then reintroducing organically grown cereals. Linseed—mixed in the proportions of one part of linseed to two parts of coarsely ground organically grown wheat, the richest source of vitamin E, the anti-sterility vitamin, is helpful as well as the green food, up to a maximum of 3 lb. per animal, morning and night. After a few days of this diet the animal is returned gradually to a production ration of 4 lb. per gallon of milk produced. The production ration should consist of one part ground linseed to three parts ground oats, with the addition when available of a little coarsely ground wheat or bran. One dessertspoonful of seaweed powder daily provides the best natural mineral supplement.

In severe cases this treatment will need to be repeated two or three times and the cow then turned out to run with a bull on a herbal ley and if possible a seaweed mineral ration should be provided in some form.

Sterility in the bull should be treated in exactly the same way, with the exception of course of the vaginal douche. The additional use of the herb, mint, especially wild mint if it can be found, or obtained from herbalists, in almost any quantity, will help to speed the cure.

VAGINITIS

Vaginitis is inflammation of the vagina, and is simply another manifestation of the condition which causes sterility or temporary infertility. Treatment should be the same as for sterility. Any kind of disinfectant douche or pessary, other than the non-irritant and natural cleanser garlic, should be rigorously avoided. Many temporarily infertile cows have been rendered permanently sterile by the use of strong disinfectant which merely irritates the delicate mucous membrane of the genital organs.

The common practice of inserting an antiseptic pessary after calving a cow, is itself often the cause of sterility. If the cow is allowed the stimulus of the suckling calf for at least four days or a week after calving the natural flow of hormones in the uterus and vagina will do all the cleansing that is necessary.

METRITIS

Metritis is a condition of inflammation in the uterus which may take either an acute or a chronic form.

The acute form of metritis is usually the result of a difficult calving or retention of a portion of the placenta or afterbirth. Another cause is the violent removal of the afterbirth causing slight injury to the wall of the uterus. Where this is internal injury effective treatment is difficult, especially if it has not been observed in time.

Freshly calved cows should be watched closely for ten days or a fortnight after calving, for any sign of swelling of the vulva, or unhealthy discharge. A healthy vulva is soft and pliant, and a clear pink in colour. Any hardening of the vulva or change in colour to a fiery red should be investigated at once. Discharges, which immediately after calving are quite to be expected, should be as clear as the white of an uncooked egg. White or yellow colouring in the discharge, or undue blood, call for a closer examination of the cause.

Acute Metritis Treatment

Though fasting always helps the healing of a wound, the length of the fast will depend on the condition of the animal. Acute metritis caught soon enough will not necessitate more than a day's, or two days' fasting, whereas when the condition has become chronic a longer fast is necessary to enable the system to dispose of the accumulated pus.

Green food only should be given when the fast is ended, or in winter some good hay may also be fed, but a light diet only is necessary. The system is always better able to carry through successful healing when the digestive process is either stopped completely or kept at a minimum.

Chronic metritis may be the result of an injury to the uterus during calving, which treatment has failed to cure, or acute metritis which has been left untreated, or, more commonly the cumulative effect of a long period of denatured feeding which has produced wastes in the region of the uterus which have, when the opportunity occurs, to be discharged. The opportunity for this discharge comes after calving when the uterus is empty. This results in yet another form of temporary sterility.

Treatment should be exactly as for sterility, see page 134.

INJURIES, CUTS AND WOUNDS

The most common injuries experienced by a cow are cut teats, broken horns, or torn skin.

In all cases of cuts, whether on the teat or other part of the body, the first need is to get it clean. There is nothing better for this than a weak solution of salt and warm water, followed by a rinse with cold water. I do not favour disinfectants of any kind. The wound will not turn septic if it is clean and the only way to get it clean is to use water, water and water. Every disinfectant of a chemical nature has the object of destroying bacteria, which are part of the healing process. It also has the effect of delaying the healing of an open wound by irritating the exposed nerve ending and depressing the blood plasma and hormone secretions which 'knit' the wound together. The only 'disinfectant' I know which does not have this delaying effect to the process of healing is garlic and even this should not be used, except initially.

If bleeding continues apply a cold water pack, renewing the cold water as often as possible. This is prepared by soaking a clean cloth in cold water, and folding it to form a pad rather larger than the wound, apply it by pressing it on to the wound by hand, repeating until bleeding stops. Then if it is possible to tie the pack on, leave it there for a few hours, recharging it with cold water as often as convenient until the wound appears to be closing. Then leave it to dry.

A cut teat may be treated in the same way as any other cut or wound, but if the cow is in milk it will be necessary to wrap it with waterproof adhesive bandage or tape. The wrapping should be kept as dry as possible and renewed as often as necessary to keep it clean. If the cut is so big as to prevent milking by hand or machine, a teat bougie (available from veterinary instrument suppliers) should be inserted to draw the milk. It is wise to keep a bougie in your veterinary chest in readiness.

If the horn is damaged, but not completely broken away it may be saved by a dressing of Stockholm tar, after washing in a solution of garlic and water, then bandaged in such a way as to hold it in position. If the outer shell of the horn comes away without breaking the core, protect the core with a bandage for a few days, then dress it with Stockholm tar and leave it to harden as it will.

Disease

Symptoms

Cause

Prevention

Treatment Sequence

Abortion

(page 112)Premature signs of imminent calving

Deficient diet or overfeeding. Catarrhal accumulations, discharging in uterus

Natural methods of management. Fast animal first signs, garlic and birth herbs, senna or rhubarb illl laxative

Give suckling calf. Then treat as sterility.

Acetonaemia

(page 114)Sweet, sickly smell of breath--off food, listless

High protein feedling and forcing milk yield

Low protein feeding, ample natural food. Minimum food just before and after calving

Immediate fasting; treebarks and molassas gruel. Leaf-plasma tablets, enemas daily during fast; then bran mashes, hay

Actinomycosis or Wooden Tongue

(page 116)Swelling and hardening of base of tongue or throat

Iodine deficiency

Regular use of seaweed powder in the diet--herbal leys

Fast; 1 pint molassas, 6 garlic tablets a.m. and p.m., 2 tablespoons seaweed powder twice daily

Bloat or Hoven

(page 118)Distention of first stomach

Fermentation set up by undigested foods in conjunction with clovers and grasses

Fast cows 12-24 hours before putting on lush grass. Give charcoal to adsorb gasses. Sow and use only herbal leys (see page 91)

In severe cases pierce stomach; 1 pint linseed oil; charcoal. Twisted rope of hay down throat; rubber tube in anus. Fast before further food.

Calf Scour

(page 120)Diarrhoea

Excessive or dirty food; too much protein

Control milk to 5-6 lb. daily--direct from cow

Fast 24 hours; cold water and garlic; controlled suckling

Cow-pox|

(page 133)See Teat sores

Eczema

(page 132)See skin diseases

Grass Tetany

(page 130)As milk fever but more sudden

Acute form of milk fever

Low protein feeding--light diet 2 weeks before and after calving

As milk fever

Husk or Hoose

(page 121)Husky cough in late summer and autumn; usually young stock

Lung worms from wet grass

Graze young stock on young leys--bring in when wet from late summer onwards

Fast for two days; heavy garlic dosage followed by generous dry feeding

Johne's Disease

(page 122)Insatiable appetite followed by severe scouiring with bubbles in dung--then loss of appetite and wasting

Intestinal fermentation of undigested artificial foods. Unnatural rearing as a calf

Natural foods rich in minerals; herbal leys; periodic fasting where any artificial food is used. Natural suckling of calves

Fast, keep intestines free of food as long as possible; garlic, enemas daily--then powdered fenugreek and treebarks gruel

Joint--ill

(page 125)Thickening of a joint--abscess on navel

Toxic condition of calve's dam--iodine deficiency

Mineral rich natural diet for pregnant dam. Seaweed manuring and feeding.

Fast on honey and warm water 1 or 2 days; 2 garlic tablets a.m. and p.m.; 24 rhubarb tablets or senna tea nightly; teaspoon seaweed powder, a.m. and p.m.

Mastitis

(page 128)Abnormal milk; inflammation of udder

Catarrhal condition due to overfeeding or deficient diet

Natural feeding, ample green food organically grown. No forcing

Fast, garlic, cold water packs on udder and ind quarters; enemas if fast prolonged

Milk Fever

(page 128)Padding hind legs after calving--collapse and coma

Excessive stimulation of ilk secretion, generally too high protein diet. Mineral deficiency

Mineral feeding from organic source--light diet 2 weeks before calving; fast 2 days before and 1 day after calving

Inflate udder--2 tablespoons seaweed powder in molassas three houirly; 2 leaf-plasma tablets 3 hourly. Keep cow sitting up

Mange

(page 132) See skin diseases

Red-Water or

Murrain

(page 131)Discoloured urine--off food

Tick bites

Re-seed pastures with ground limestone dressing--sheep to graze with cattle

As husk, plus 2 lb. common salt anda treebarks gruel; 2 pt. linseed oil and 2 oz. turpentine

Rheumatism

(page 131)Lameness. Sometimes swelling of joints

Unnatural feeding, causing accumulation of acids in joints

Natural diet of mainly fresh food. Regular use of garlic

Fast for 1 week or longer--4 garlic tablets a.m. and p.m. Rectal enemas daily -- then organically grown green food.

Ringworm

(page 132)Circular raised ring of dry, scabby flesh. Loss of hair

Parasite, in conjunction with malnutrition

Healthy diet; good nutrition; clean conditions

Iodine dressing, followed by herbal healing cream. Green food laxative

Skin diseases

(page 132)Scurfy, mange, loss of hair or dry skin

Deficient diet, dirty conditions or parasites. Excessive feeding also a cause.

Good nutrition; clean conditions of housing

Wash and apply herbal healing cream. Green food laxitive

Sterility

(page 134)Failure to breed

Unnatural diet, excessive milk production, catarrhal accumulations. Nature's demand for a rest

Mineral rich organically grown fresh food. Avoid excessive feeding or too frequent calving. Allow calf to suckle dam for at least one week

Fast for 1-2 weeks. Rectal and vaginal enemas; 6 garlic tablets a.m. and p.m.--birth herbs--green foodonly for 5 weeks. Run with bull.

Vaginitis

(page 135)Vaginal discharge

Metritis

(page 136)Vaginal discharge

Teat sores

(page 133)Scabs and sores on teats

Damage during milking--cuts. Disinfectants in washing water

Care in milking; use no disinfectants

Herbal healing cream--wrap sore with waterproof adhesive t ape--keep dry after dressing

Worms

(page 122)See Husk or Hoose

GESTATION PERIODS OF VARIOUS ANIMALS

ASS: 12-1/2 months, 380 days.

MARE : 11 months, 340 days.

COW: 9-1/2 months, 40—41 weeks, or 281 to 285 days.

EWE and GOAT: 5 months, 20—21 weeks, or 140 to 147 days.

SOW: Less than 4 months, but over 16 weeks, 110 to 120 days.

BITCH : 9 weeks, 63 to 65 days.

CAT: 7—8 weeks, 50 to 56 days.

HEN sitting on eggs of the HEN: 21 days (19 to 24 days).

HEN sitting on eggs of the DUCK : 30 days (28 to 32 days).

DUCK sitting on eggs of DUCK : 30 days (28 to 32 days).

GOOSE sitting on eggs of GOOSE : 30 days (28 to 33 days).

TURKEY sitting on eggs of TURKEY : 26 days (24 to 30 days).

OESTRUM (HEAT) PERIODS