HERDSMANSHIP

by

NEWMAN TURNER

A guide for the herd owner, herdsman and cowman, on the

establishment and management of a pedigree herd of dairy

cattle of any breed, including the selection, breeding, feeding,

preparation for show and sale, how to judge, and on-the-farm

prevention and treatment of cattle diseases

FABER AND FABER LIMITED

24 Russell Square

London

First published in mcmlii

by Faber and Faber Limited

24 Russell Square London W.C.I

Printed in Great Britain by

Latimer Trend & Co Ltd Plymouth

All rights reserved

TO

THE JERSEY COW

WHICH COMBINES BEAUTY

WITH EFFICIENCY

CONTENTS

Preface

Section One

ESTABLISHING THE HERD AND THE

BASIS OF PRACTICAL BREEDING

1. My start in herdsmanship

2. Selecting and founding the herd

3. Practical breeding and simple genetics

4. Herd efficiency: Sources of increased profitability

5. A call for some cattle sale reforms: and a formula for future sales

Section Two

THE SHOWING AND JUDGING OF DAIRY CATTLE

6. How to judge a dairy cow

7. Preparing for show and showing of cattle

Section Three

MANAGEMENT FOR MILK PRODUCTION

8. Preparing the heifer and cow for lactation

9. Feeding and cropping for the dairy herd

10. Calf rearing

11. Hints for new herdsmen

Section Four

CATTLE DISEASES—PREVENTION TREATMENT

12. 'There's only one disease of animals . . .'

Abortion

Acetonaemia

Actinomycosis or Wooden Tongue

Blown, Bloat or Hoven

Calf Scour

Husk or Hoose

Worms

Johne's Disease

Joint ill

Mastitis

Milk Fever

Grass Tetany

Red Water

Rheumatism

Ringworm, Eczema, Mange, Skin diseases

Teat sores or Cowpox

Sterility

Vaginitis

Metritis

Injuries, Cuts and Wounds

Quick diagnosis and treatment chart

13. Herbal medicine on the farm and a challenge

14. Foot-and-mouth disease—can be prevented without slaughter

APPENDICES

1. Letters from successful users of my veterinary methods

2. The Why and How of the Breeds, and What to look for in each breed

'Jerseys' by Newman Turner

'Guernseys' by G. F. Dee Shapland

'Dairy Shorthorns' by Robert Hobbs

'Kerrys' by Joan Cochrane

'British Friesians' by B. J. Honeysett

'Dexters' by Lady Loder

'Red Polls' by P. T. Joyce and N. L. Cull

'Ayrshires' by S. Mayall

'South Devons' by George Eustace

3. The Composition of the milk

4. How to estimate contents of stacks, silos, clamps and dutch barns

5. Animal Health Association—advice in the use of herbs

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

While this book seeks to be comprehensive in the subject of dairy cow selection and management, it is nevertheless confined to information and guidance which as a whole is not available in any other book that I know. But I have assumed certain elementary knowledge, such for instance as the fact that a cow is milked by squeezing the teats or applying suction by means of an alternating mechanically made vacuum, and the need to give a cow a couple of months' rest between each lactation. The basic elements of dairy farming are available from a thousand sources. The desire which has inspired this book is to impart from my own experiences the knowledge and the enthusiasm which makes cowmen and cow-keepers into herdsmen and pedigree cattle breeders. Above all I want to show how it is possible so to simplify and modify the work of dairy farming as to make it a truly scientific and mutually happy association between cattle and men.

The immense and increasing toll of disease in our dairy herds need never be, and the young and rising generation of herdsmen and herd-owners who are at last beginning to adopt the commonsense methods introduced in my book, Fertility Farming and supplemented in this book, know that in their herds at any rate, it will not be.

As the son of a working tenant farmer in Yorkshire, I milked my first cow at the age of five, I regularly milked a dozen cows morning and night when I was twelve and I have been milking cows ever since. From being my father's cowman, through periods of assisting other herdowners I became my own herdsman when I took on Goosegreen Farm twelve years ago. I have been my own herdsman ever since. But I haven't always had to milk all my own cows. For first my wife and later my good Italian friend, Toni Capozzoli, milked the cows along with me morning and night, until Toni eventually took charge of the milking himself. Together we have developed a herd which has won numerous prizes and championships, both for production and inspection at all the main shows in the south-west, and as I complete this

book I am informed that in the Somerset County Herds Competitions (which take account of milk yields, butter-fat, type, bulls, young stock and general management), we had the second best Jersey herd; second only to the herd which was supreme against all breeds in the National Competition. Though I continue to be my own herdsman to this day, I could not have written this book without the devoted cowmanship of my wife in the early years and Toni for the past eight years, or the tireless attention to the manuscript of my secretary, Rae Thompson. My deepest gratitude is theirs for making my part in the joint effort possible.

Goosegreen Farm, F. NEWMAN TURNER Sutton Mallet, Bridgwater, Somerset, March 1952

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the Editor of The Farmers' Weekly for permission to use some material which I first wrote for his journal and to the following secretaries of cattle breed societies for the judging points of their breeds used in the Appendix on the 'Why and How of the Breeds'; Mr. Edward Ashby of the English Jersey Cattle Society; Mr. M. F. J. Batting of the Dexter Cattle Society; Mr. W. H. Bursby of the British Friesian Cattle Society; Mr. S. H. Dingley of the Ayrshire Cattle Society; Mr. A. Furneaux, Secretary of the Coates Herd Book (Shorthorns); Mr. R. O. Hubl of the Kerry Cattle Society; Mr. R. F. Johnson formerly of the South Devon Cattle Society (who is now Secretary of the National Pig Breeders' Association); Col. T. M. Kerr of the English Guernsey Cattle Society; Mr. A. C. Burton of the Red Poll Cattle Society. The breeders themselves who have described their methods and their breeds have my warmest gratitude.

I am specially grateful to Brian Branston for permission to quote lengthy extracts from his book, Breeding for Production, Lawrence D. Hills, who read my manuscript and made valuable suggestions, and Douglas Alien for many of the photographs.

My thanks are also due to the Principals of Wye College, the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester, and Mr. F. J. Rigby for the comparative costings on page 43.

I would also like to offer my thanks for photographs of plates 1 and 2 to West Midland Photo Services Ltd., Shrewsbury; plate 3, Wiltshire Gazette; plate 5, Independent Newspapers Ltd., Dublin; plate 28, G. S. McCann, Uttoxeter; plate 33, English Jersey Cattle Society; plates 34, 38 and 47, Farmer & Stockbreeder; plate 35, Mr. G. F. Dee Shapland; plate 37, R. Hobbs; plates 39,42 and 48, Sport & General Press Agency, London; plates 43 and 44, Lady Loder; plates 45 and 46, A. E. K. Cull; plate 50, Nicholas Home Ltd., Totnes. All other photographs are by Douglas Alien of Bridgwater.

Since the publication of this book, the author has transferred his farming operations, and Jersey herd, to a farm of 500 acres, on the edge of the Wiltshire Downs.

There, it is hoped to develop the work, and continue the experiments on a larger scale. As a major part of a comprehensive organic farming and animal health centre, an animal hospital will be established to develop, with all classes of livestock, the herbal methods of prevention and treatment of disease described in Mr. Newman Turner's books.

All communications for the author should in future be addressed to Feme House, Shaftesbury, Dorset.

Section One

ESTABLISHING THE HERD

AND

THE BASIS OF PRACTICAL

BREEDING

Chapter 1

MY START IN HERDSMANSHIP

There are cows and cows, and the animals with which I started my lessons in herdsmanship on my father's farm in Yorkshire were just cows. Any question of a breed never occurred to us. But we valued our animals and studied their needs even more than the few hobby farmers who at that time owned pedigree herds. Even as recently as that time, thirty-odd years ago, we were completely oblivious of the many diseases which beset the animal breeder of today ; veterinary surgeons devoted most of their time to horses; the maintenance of health in the herd was mainly a matter of growing good food and feeding it to the cows in adequate quantity. The successful farmer was the man with an instinct about animals; a knowledge of viruses and bacteria was not necessary. Farming was an art and not an industry beggared with 'scientists' and petty officials. Farming could only properly be performed by men who had it in their bones; there was little hope for the man who had put it all in his head. There was no ready-made answer available in a book, and very few ready-made remedies served up by the manufacturing chemists, though even then they were already founding their fortunes on the farmer's misfortunes.

Though our cows were no particular breed at all, for want of a name they were generally considered to be Shorthorns. That must be no reflection on the Shorthorn breed of to-day. It is merely the fact that the Shorthorn breed embraces such a wide variety of colours that for general purposes an unidentifiable cow was called a Shorthorn, just as to-day a black-and-white cow, whatever its origin, is considered by the commercial farmer to be a Friesian, though pedigree breeders deplore this loose use of breed description. Strictly speaking, I suppose the words cross-bred should precede the use of a breed name where a pedigree is not available, or even when the animal is not registered in the official herd book. But the difference between a registered and an unregistered animal meant little to us. Breeds for us were distinguishable by colour rather than names in a book in London.

What characterized our cows was the uncertainty with which they transmitted their propensities to their offspring, if at all. This provided us with a certain thrill of anticipation each time a cow was to give birth. But the bank manager rarely found that thrill a satisfactory substitute for the economical yields which planned breeding would have produced. Consequently as often as a good cow gave us a heifer as good as herself or better, she gave us a dud which was quite incapable of a profitable life in the herd. This complicated our farming by making it necessary for us to dabble in beef production, mixing it as need arose with milk production, and because of the difficulty of properly assessing the potentialities of each heifer until she had done a lactation, it meant we were engaged in the least profitable kind of beef production, that is cow beef or at best, heifer beef, whenever our guesses about the milk production capability of the animals we bred failed to come off.

Similarly when I started farming on my own account at Goose-green, I took on a good commercial herd of Shorthorns which had a slight sprinkling of Friesians and their crosses. Though in our first year or two we were able, by heavy feeding, to get the herd average up to about 700 gallons, which was extremely good as a start with non-pedigree cattle, their daughters didn't even approach that yield, excepting the occasional fluke, though we used three different pedigree Shorthorn bulls. Yet the daughters of the only pedigree cow we had, a Friesian, by different Shorthorn bulls, all did slightly better than she (though she herself was a 1,200-gallon cow). It became clear to me then that I must have cattle which, like my Friesian, had behind them some ancestry of transmission certainty. And this could only be got by pedigree breeding. Pedigree breeding has often been called a rich man's hobby, but this experience demonstrated that in my case at any rate it was likely to be a poor man's passport to profits. And indeed it proved to be. I decided to change over to exclusively pedigree cattle, and it was as though I had been blindfold until that time, for breeding for milk production became a simple process of planning, whereas before it had been impossible guesswork.

There were other factors which helped my decision to change over to pedigree cattle, the chief of which was disease in the herd which made some drastic changes necessary and provided an opportunity to bring in a pedigree nucleus. But I will say more about that in a later chapter, as in another chapter, too, I will explain my choice of breed. But the fact of disease, especially abortion and tuberculosis, decided me to change over gradually, replacing the Shorthorns as they calved down, with pedigree Jerseys.

There are two systems of founding a dairy herd, both of which are reasonably safe for the inexperienced buyer. One is to go to an established herd, which has shown consistent breeding over a number of years and buy a nucleus of heifers with good production figures immediately behind them, and a bull of the same family. The other is to buy old cows that have done good records, in-calf if possible so that you have at least a calf to come if the cow herself is at the end of her career. The old cows should, if possible, be of the same strain so that you start one step along the path of your breeding policy, but don't be too rigid about the strain if the cow you want is good. It is useless to buy a cow because she is of the strain you want if she happens to be a particularly poor specimen of that strain, though it is not impossible to buy a good fluke in that way. I once did. But once in a lifetime is as much as you can expect.

My 'fluke' was bought at a Jersey Show and Sale at Reading. She had won nothing in the ring, her highest lactation yield had been 400 gallons, she had a badly shaped udder, but she was a pleasant-looking animal and of extremely good breeding. She first came into the sale ring and was bought for 100 guineas by a very famous breeder. Why, it is difficult to imagine, for she would not have made any contribution to his already fabulous herd. Perhaps he was buying for a beginner, friend, or neighbour. But he changed his mind and the cow came back into the ring at the end of the sale with the explanation that she had been bought by mistake and was being offered again by her purchaser. This, of course, aroused suspicion. But being compelled by some inner impulse, a hunch, if you like, though I think hunches generally have a little evidence to support them, when the bids got to 40 guineas and stuck, I decided that at such a price she was worth buying as a foster mother for some calves I had. I got her for 60 guineas. She never did anything more than 400 gallons—her udder just wasn't made for more—but she bred me three good daughters, one of which gave 1,000 gallons with her first calf, and 1,500 with her second at 5-6 per cent butterfat, the second I sold before I knew the capabilities of her sister, and the third looks like doing as well as the first.

But that is just one of those things that never happens again. It is as well in laying the foundations of a herd to forget that such possibilities exist, and don't be tempted by what appears to be cheap unless there are factors affecting the price which you know about and can remedy, but about which competing buyers are ignorant.

Chapter 2

SELECTING AND FOUNDING THE HERD

In spite of the gamble involved in buying at sales I felt my capital was not enough to enable me to do much buying privately from breeders. I thought I knew enough about cattle to avoid the worst troubles. Yet there was hardly an animal of the foundation cattle of my Jersey herd which did not have some trouble, and of about fifty females I bought in the first five years, only three of them stayed five years and what is more they stayed only as a result of my own success with the natural treatment of disease. One of them was sterile, another a habitual milk fever case, and the third had mastitis in two quarters when I got her home from a sale. All the others, bought both privately and at sales, have left this life because they suffered from some defect of health.

I do strongly advise newcomers to pedigree breeding to place themselves in the hands of a reputable breeder and take what heifers he can offer at a reasonable price, or let him find someone else's worth buying and pay him for doing it. It will be money well spent if you can persuade an experienced man to do it. I fear, however, most breeders would consider it too much of a responsibility.

When I wanted to buy a bunch of heifers in Jersey I had no knowledge of conditions there and employed a breeder to conduct me from farm to farm and seek out suitable animals for sale at the price I was prepared to pay. At the end of a day touring the island and buying ten heifers I paid him £35 commission. At the time I was most reluctant to do so. But the animals did survive which is more than could be said for those I bought myself in England.

In England I didn't think myself in need of expert advice, and in consequence I paid very much more the other way by buying animals entirely on my own responsibility and taking the very costly consequences.

I followed both systems referred to in establishing my herd. I bought privately seven bulling heifers, and their half-brother. They were run with their half-brother with the idea of starting a breeding policy a step ahead of myself, so to speak. It didn't come off, for each one of these heifers produced either a dead calf, or a bull, and all but one died before they produced me a single live heifer calf. Of my original nucleus of heifers I have no descendant for most of them had had husk when I bought them, though it was not evident at the time. They nearly all got into a serious condition with parasitic pneumonia and became useless before calving their second calves. One died of acetonaemia (my first case and the only one I've failed with). One only survived. So much for my efforts to establish a line bred herd. But I still believe the best method of starting is the purchase of heifers from a reliable breeder with, if necessary, the assistance of another experienced breeder.

The other way—buying old cows—brought me almost as much trouble but it did produce some calves and it was really from this miscellaneous collection of old cows that I built my present herd. This is a slower way of establishing a herd, for unless the cows are all of similar strains, the concentrating of characteristics cannot be controlled except through the bull. This means that the first crop of heifers carry only a half of the particular breeding that is wanted, whereas in the case of heifers of the same strain as the bull the resulting heifers carry a double concentration of the breeding. And if both the bull and the heifers are themselves line bred from consistently healthy long-lived and good-producing animals then profitable and consistent breeding is almost certain to continue. But few of us can expect our herd building to start so well. Mine, by the failure of the vital nucleus of heifers which I got to mate with the bull, certainly didn't, so I got off to a one-legged start; it did nevertheless enable me to introduce a slightly different strain to improve the one I had originally chosen, and by this blend of breeding develop my own strain of strong-bodied efficient converters of home-grown food, which I could not have found ready-made for me in any of the recognized strains, and certainly not in the fashionable strains.

The question of whether or not to pay high prices is one which must trouble those with the money available. For the man with limited capital the problem is whether to buy a few at the top prices, or more at lower prices. For both types of buyers, it is wise to get the best that money can buy and few rather than many. A few good cows, done well, will pay better than a lot of second-rate animals done moderately well. The animals which make record prices at auction sales may be left well alone, for the price is probably being paid for some fashion fad or some freak performance. The payers of record rices are generally wealthy industrial magnates and not sound judges of a good cow, though they often employ men who are sound judges. An alternative policy, if financially possible, is to buy young animals (stirks, perhaps) and only a very few milkers. That means waiting two years or more before the herd begins to become a milk-producing unit: and of course it requires capital. But decide upon the cows you really want, with the help of an experienced breeder if necessary, and be prepared to pay well. The few comparatively high-priced animals will multiply more quickly than you would imagine and patience in accepting a rather lower milk cheque for the sake of really sound animals will be well repaid in the quality and value of the resultant home-bred heifers.

If you must have a good-sized milk cheque coming in, then hang on to some of your best yielding commercial cows (if you are changing over from a commercial to a pedigree herd), or if you are starting from scratch, buy a few heavy yielding old cows which have two or three lactations to come. Whether or not these old cows are of the chosen breed, or commercial cross-bred animals, will depend on the price at which they can be found, and whether or not you have the patience to tolerate a mixed herd for a number of years.

Having a Shorthorn and Friesian cross-bred herd and being very limited for capital when I decided to change over to pedigree Jerseys I had not much choice in the matter. I bought my bunch of seven heifers and their half-brother for the nucleus of my future herd and then, in order to keep the income going I brought in old Jersey cows as I sold out the cross-breds. But I made the mistake in the beginning of buying freshly calved old cows in order to get milk quickly and many of them had obviously been sold as difficult or declining breeders. For in some cases they never bred again. There can be no means of protecting the buyer against breeders who sell animals which have finished breeding, but it is hard on a young farmer, just starting with very limited capital, to have to pay an established and successful breeder 100 guineas, as I did on one occasion in the early years, when 100 guineas was not a modest price to anyone and was a small fortune to me, and to have no redress. It is part of the game at the moment. But the time must come when sales under the auspices of the breed societies are confined to cattle guaranteed in udder, breeding and milk yield. Anything which cannot be so guaranteed must go into the commercial market and be bought by the man who has the money to squander or the courage to take a chance. But I have more to say on the need of cattle sales reforms later (see page 47. Chapter 5.)

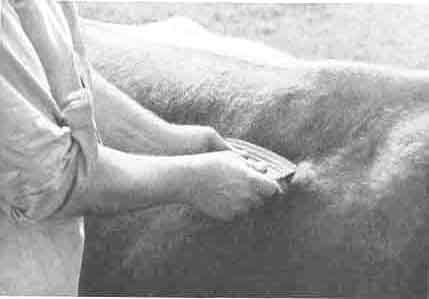

If, instead of freshly calved animals, in-calvers are bought, at least one has the chance of getting a heifer calf should the cow herself prove to be a bad breeder. But the risk with in-calvers is that they are being sold for udder trouble, which will fire up when the udder freshens for calving. It is therefore doubly necessary in buying dry in-calf cows to examine the udder with extreme care. Experience of my mastitis treatment (page 126) will give confidence to buy animals in spite of threatened mastitis for if the cow is treated immediately she calves there is no reason why she shouldn't be cured. But for buyers who as yet have no experience of my treatments, more caution is necessary. Defects to guard against are hardening or thickening of the teat channel or pea-like lumps or obstructions in the teat channel. When the liquid is drawn from the teats it should be a sticky, gummy 'honey' which, though clear with a heifer in calf for the first time, will be slightly cloudy with a cow that has had a calf. Avoid the watery or highly coloured discharge. Be confident with the clearer honey-like discharge which indicates a dry udder in perfect health which will not go down with any kind of trouble at calving time.

Other important guides to the health and productive ability of a cow may be mentioned here as a help to prospective buyers, for little enough protection is given to the buyer and while breed societies are governed by vendors I see no great prospect of improvement. These points do not strictly come under the eye of the judge in the show ring, so I mention them now, instead of in my chapter on judging.

The vulva should be soft, pliable and a healthy pink colour when the folds are drawn apart. A tough leathery or hardened vulva with pale coloration is one of the signs of a difficult breeder, for it is the mirror of an unhealthy uterus within. Spots of catarrh or discoloured discharge from the vulva or on the walls of the vagina when opened for examination are an indication of leucorrhea or other uterine discharge which while it continues will prevent breeding.

Any discharge from a cow close to or just after calving should be clear and free from white flecks. Any discoloration or catarrhal appearance is a sure sign of a diseased uterus. This is not to say that it cannot be cured; it quite easily can be by my treatment for sterility (page 134), but allowance should be made for this in estimating the value of the cow.

Fat around the tail setting and pin bones is a sign of sluggish reproductive organs. A bony tail setting and pin bones with complete absence of surplus flesh or fat in those regions are the mark of a good breeder and hard-working cow.

Tail setting. A definite dip in front of the tail setting or farther forward or a very marked sagging of the loins may mean a mechanical interference with the proper functioning of the uterus and should be avoided.

The swollen or 'big' knee, though very occasionally due to a knock, is almost invariably caused by an accumulation of toxins in the system. The gathering of this accumulation around the knee joint is nature's protection for the reproductive organs and lungs of the cow. But it is an obvious sign that the cow is in a toxic condition and would benefit by an internal cleansing treatment such as I have set out for sterility (page 134). It is almost certain that, though at the outset a big knee is harmless, if the feeding and general management which gave rise to it are persistently continued, the ability of the system to localize the accumulation in places where it can do little or no harm will be lost, for there is a limit to the amount of rubbish the system can deal with. After the knees—the uterus or lungs must be used as channels of discharge; then real trouble follows.

Eyes should be bright and intelligent. If you can't get a clear and colourful reflection of yourself in the cow's eye she can't be in good health. A dull eye is the window of a sour stomach and a sad heart; pass it by!

Mouth. Teeth should be straight, evenly placed in the gum, and of course, all there. Jaws should meet evenly all round and be neither under nor overshot. Either of these faults will interfere with grazing, though the cow could live well on hay, silage and other stall feeding, and such an animal, if born into the herd, should not be destroyed. Indeed some calves may be born with undershot jaws which correct themselves as they grow older.

Skin must be thin, loose and pliable, especially over the ribs. A handful of skin pulled away from the ribs should come away easily, feel silky in the fingers, and go back like soft elastic when released.

Chapter 3

PRACTICAL BREEDING AND SIMPLE GENETICS

Having selected the cows, successful breeding demands some knowledge of genetics; some farmers have an uncanny ability almost to know by looking at a cow and a bull whether they will milk well if mated. But such ability is only for the few whose animal instinct amounts to genius. Mr. George Odium, the famous breeder of the Manningford Friesians, in his writings and lectures says much about transmission, recessive factors, genes and other involved genetical theory, but in spite of his immense and detailed knowledge I credit much of his breeding success to a mixture of genius and good luck.

Those of us who can expect neither of these are left with ample opportunity to acquire good judgement and wide experience. Both grow with use and in that respect we may score over the mere lucky genius.

But there is no need to wade through the many books on the subject of animal genetics in order to acquire the knowledge which makes a good livestock breeder, though it is well worth any breeder's or herdsman's while to get as much book knowledge as may be obtained from the excellent little book, Breeding for Production, by Brian Branston (Faber). This will cut out a few of the unknown factors in the practical breeding side—but the only real way of learning breeding is to breed. Put Bull A on cows B, C, and D, and see if the results are AB, AC, AD. Study the progeny beside their parents and see for yourself which characteristics have been inherited from which parents, and which appear to have come from nowhere. With an old breed like the Jersey it is a fairly safe gamble that A on B will produce AB, but with some breeds, especially dual-purpose breeds which carry both flesh and milk factors, not even an Odium can forecast the result. Consistent breeding of dual-purpose cattle can without question be achieved, and some of our leading Red Poll and South Devon herds in particular are outstanding examples of consistent breeding, but the process is longer and the beginner may expect consistent results more quickly and more easily from the breeds which have concentrated on milk or butter yields, and have produced animals with only one, or at most production purposes.

Far more can be learned about breeding by looking at cows and bulls, their progeny and their records, than by looking at books. Many a townsman has scoffed at the farmer wasting his time 'leaning on the gate', but if his animals are in the field, that is how he learns and improves upon his skill as a livestock breeder; that is how he improves upon his crops. Farmers nowadays have all too little time to lean on the gate and think, which is a pity, for I am quite sure that moments of contemplation and moments observing the growing crop or the grazing animal are the farmer's most profitable moments, materially as well as spiritually.

I could tell you the sire of any of my home-bred females, merely by looking them hard in the face, and I have eight bulls in use. Admittedly this is not easy in the first days of a calf's life, but as the calf grows to maturity the characteristics of both parents become plainly evident to the observant. This kind of observance is the only way to know exactly whether the breeding policy is working out right or wrong.

Because I think Mr. Branston has provided in farmer's or herdsman's language the essential knowledge of genetics, I will quote some valuable extracts which I endorse. I hope these extracts give an outline of an excellent and absorbingly interesting book which will make every farmer, breeder or herdsman who reads this book, read also, for the full story of sensible breeding, Brian Branston's book. In any case they provide the 'heart' of the subject which will enable readers of my book to grasp the basic knowledge of animal genetics necessary for the practical man:

'Hereditary

'An animal which may breed one way or the other for a certain factor I shall call a mixed-breeder for that factor. (The geneticist calls such animals heterozygotes.)

'The practical breeder of animals for utility must always be on the look-out for animals which are mixed-breeders for the factors which help to make his living so that normally he can bar those animals from his breeding plans; just as he must search for and retain those animals which are self-breeders (homozygotes) for the factors he needs. . . . What is the breeder to do when the outward appearance of animals is similar but their breeding performance is different?

'An example to illustrate outward similarity and different genetical make-up can be taken from Mendel's sweet-pea experiments. Mendel found that some peas were self-breeders for red flowers and some for white flowers: when he crossed a red with a white he got all red offspring. But if he mated two of these first-generation reds together he got offspring in the proportion of three reds to one white.

'Obviously, in this coupling the first cross red offspring only appear to be like their red parent, because no matter how many self-breeding red parents you mate together you will always get red offspring: if you had only red marbles in a bag no matter how often you shook up the bag you would always pick out a red one. But in mating together red offspring of sweet peas where the one parent was self-breeding red and the other self-breeding white you get a proportion of three reds to one white. When a trait in one of the parents dominated another, as the red dominates the white in the red and white pea parents, Mendel called that trait dominant. The white he called recessive because although it had disappeared entirely in the first cross offspring, it nevertheless came out in the crosses between those offspring : it had only receded into the background.

'If we were to continue breeding from the second-generation flowers we should find that one red would be a self-breeder for red; two reds would be mixed-breeders for red and white in the proportion 3:1, and the white would be a self-breeder for white . . . one red breeds true, two reds breed untrue, and one white breeds true. In other words, the appearance of two of the reds is not what it seems. This comes home to the dairy farmer, say, when he realizes that some of his best yielders for both milk and butterfat may possess those qualities only as the first cross sweet peas possessed the colour red: they may be mixed-breeders for both factors. This is indeed tragic when one remembers that the average number of calves born to dairy cows in this country at present is only a little over two. Both of these may quite easily be the two mixed breeders out of the four. If, in addition, the farmer's bull should turn out to be a mixed-breeder for milk and butterfat then he could do great damage in the herd. It is unfortunate that it is impossible by looking at a cow or a bull to tell whether it is a mixed-breeder or a self-breeder for milk yield and high butterfat. We cannot tell this even by looking at its parents or grandparents ; nor by studying its pedigree; nor, if it is a female, by studying its milk yields (that is only comparable to looking at the red first cross of the red and white sweet peas and seeing that it is red); nor, yet again, by studying the records of the milk yields of its dam.

'The only sure way of distinguishing a self-breeder from a mixed-breeder is by sampling their offspring: the inescapable conclusion is that you can only tell how an animal breeds by finding out how it has already bred. 'By their fruits ye shall know them.'

'Since a farmer needs as far as possible to keep animals which are self-breeding for the most perfect set of inherited qualities, and since a start has to be made somewhere, he must get together complete data about the breeding performance of his animals used for reproduction. There must be no hiding of defects. A farmer who tries to work without records is playing blindman's buff among his cattle. A pedigree breeder who hides defects in the stock he intends to sell is Agriculture's Fifth Columnist. . . .'

'Inbreeding

'Inbreeding is the one certain way to bring into being self-breeding groups of animals, to diminish variability, to give uniformity.

'Inbreeding will always result automatically in self-breeding animals ; but the important thing for the practical breeder to realize is that those animals can be self-breeding for defects as well as for good qualities. The farmer must decide and then select those animals which are to be inbred, his purpose always being to bring together the greatest number of good qualities and the least number of bad qualities which will be fixed in his self-breeding stock. Breeders should never start inbreeding with inferior stock, in fact they should never start inbreeding with a group of animals in which the best are not quite as good as their owners would wish them to be.

'Inbreeding coupled with selection is the quickest way to produce self-breeding animals—animals which will transmit as they express.

'Neither is selection the same thing as culling. Culling is the traditional method of raising the standard of a dairy herd or a laying flock of hens—and it is wrong as a standard method for a number of reasons. Culling (as in the case of recessive "reds") does nothing to raise the quality of the flock or herd; if the breeders remain untouched then another crop of culls must automatically come along. Economically, culling alone as a standard practice year after year is foolish. In a dairy herd, for instance, low yielders are culled after they have made their low yields (more often after two or three low yields than just one—because they have been given "another chance"). This means they are culled after the owner has lost money. The sort of herd a commercial dairy farmer will have fifteen years from to-day depends not on the cows he culls but on the sort of bulls he uses in the meantime. It is bulls not culls that are important. In present conditions the commercial dairy farmer with a small herd of up to fifteen cows would be better off not culling but using his worst yielders to breed beef stores.

'The owner of a pedigree herd of milk cattle on the other hand needs to cull and cull hard to eliminate the low-yielding individual and even more so the low-yielding family. But he must cull with a knowledge of the genetical make-up of his animals—he must cull from a knowledge of the individual's power of transmission as well as its expression. When he does this he turns culling into selection. Culling is a negative practice and leaves the situation much as it was; selection is a positive thing and makes for improvement. . . .

'Part of the stigma which appears to be attached to inbreeding is not due to man's own conventions of morality, it is a result of economic loss from aberrant offspring which have cropped out where inbreeding has been tried.

'These aberrant offspring are not caused by inbreeding, they are caused by aberrant factors being present in double dose in the material used for inbreeding. The only way to get rid of such material is not to stop inbreeding, but to continue it more intensively until all the scum has found its way to the surface and been skimmed off. Or else, of course, to discard the aberrant stock entirely . . . .'

'Out-Crossing and Line Breeding

'Inbreeding reduces variability and makes for uniformity. Sometimes it may build up a uniformity like a prison wall with the genes inside as prisoners: as inbreeding is continued the genes can group together among themselves but have no contact with other genes in the outside world. The faculty for self-breeding produced by continued inbreeding is the prison wall which confines the genes.

'We may find it necessary to bring back within the walls genes which have escaped before the coping stones were put on; or to introduce genes that have never been inside. Or else we want to remove an obnoxious prisoner gene. The way in which we break down the prison wall so laboriously built is by out-crossing. The unfortunate thing is that we cannot control the exact type and number of intruders through the breach we make in our prison wall, nor can we be certain that some of the model prisoners we wish to retain will not escape while the wall is down.

'In straightforward language and forgetting the flowers—out-crossing is an evil—sometimes a necessary evil. The object of animal breeding for utility is to make the group self-breeding for the inherited make-up of the best individuals; out-crossing destroys self-breeding and reintroduces mixed-breeding individuals. We may get the factor we want, but we shall undoubtedly get a number of factors we do not want, and so the slow process of turning out the unwanted ones begins again.'

'Minimizing the Risks Involved in Out-Crossing

'If you are bound to out-cross, first make certain that the out-cross animal really is a self-breeder for the gene or factor you want to bring in. Next, confine the effects of the cross to a small number of the group you wish to change. The hybrid offspring must then be bred back to the pure-bred group, and from the offspring of such matings only those few which show the most improvement in the factor required should be kept.

'These few animals should again be bred back to the pure-bred group, and this procedure continued for four or five generations—more if possible.

'With the exception of animals needed for the work, those produced by the repeated back-crosses should be discarded for breeding purposes—even though their quality be above average.

'In polygamous animals no males derived from an out-cross should be used for at least four to five generations: the new genes being introduced through the female lines where the impurities they bring handcuffed to them can do less hurt. The common sense of this is obvious. A bull will spread himself quickly through the herd, but a cow can be made to confine her impurities to three or four daughters.'

'Where to go for an Out-Cross

'Where should the anxious breeder go for an out-cross? Preferably he should stay within the breed if he can locate a strain which is outstanding in the qualities needed to be introduced or improved.

'Provided the breeder knows how heredity works and what the results of his actions are likely to be, then out-crosses from other breeds may be used with success. And a breeder who has had an eye open for the need at some future time of out-crossing may have prepared his way by line-breeding.'

'Line Breeding

'You always find somebody who asks " What's the difference between inbreeding and line-breeding?" and there is always somebody else at hand to give a senseless though "fly" answer.

'The truth is inbreeding and line-breeding are essentially the same process. A breeder practises line-breeding who, instead of inbreeding his whole flock or herd, inbreeds them in separate self-contained groups. He produces parallel inbred lines.

'Then if the necessity blows up he has the chance of reintroducing genes from one parallel line to the other without recourse to a violent out-cross and with far less danger of bringing in impurities.'

'Out-Crosses and Show Points

'For utility animals the faculty for self-breeding is the main aim after quality.

'For show animals the individual and not the group brings home the cash: so an out-cross may introduce just that exaggeration of fancy points which will catch a judge's eye.

' But such an individual will leave a long smear of impurity behind it if bred from. Such animals are the prize-winning slugs of the utility farming world. ...'

'Test Mating and Progeny Testing

PROGENY TESTING

'Progeny testing is a method of finding out the general efficiency of a dairy bull (for example) for producing the kind of daughters a breeder requires.

'It simply entails the registration of the performance of his female descendants. If it is not possible to take figures for all a bull's daughters then a random sample should be taken, say the first-born ten or twenty. The progeny must in no way be selected or any value the record might have will have been destroyed at the start.

'A bull's certificate to continue as pilot of the herd, to continue breeding, should be the excellence of his breeding report. The statement of his breeding value should show the number of female calves horn, the number raised, the number discarded, the number of days milked of every heifer and the results in yield and butterfat.

'A proven bull is not necessarily a good bull; but a proven bull which is prepotent (that is to say "self-breeding") in the factors which make his owner's livelihood and the country's prosperity and health, is worth his weight in gold. . . .'

My first Jersey bull had three outstanding characteristics which he transmitted to every one of his daughters and a fourth hidden characteristic which he carried from his dam. The first, cocked horns and a rather plain face were rather annoying and valueless, except as an indication that the old boy was transmitting something of himself consistently. The second, a colossal barrel with widely sprung ribs and deep belly were admirable for a herd such as mine fed on home-grown foods. The third, strong, squarely placed straight legs—both back and front. Neither belly nor udder will stay the pace without sound legs to carry them and to carry them a long way when the cow has to graze her own food. The fourth is of course considered the most important—a good udder—though I think the stomach capacity more important. A good udder is useless without the stomach capacity to fill it. Many a bad udder has produced a lot of milk through a big belly but I've had perfect udders under flat-sided barrels which have produced unbelievably poor yields.

Having found that my bull transmitted the important conformation characteristics the question was what to do about the bad head. It is usually argued by the milk-at-all-costs boys, 'Why worry about the head?' But I have found that an intelligent, though not necessarily a pretty face, denotes the ability to produce efficiently. I have never known a cow which is an efficient milk-producer to have an unintelligent face, which may sound a tall story to the man who hasn't spent as long as I have looking cows in the face, and who may consider all cows' faces patently dumb anyhow. But I suggest, if you have an eye for an animal which looks deeper than first impressions, that you make a study of the heads of your best milking cows, and particularly the cows which are known to be efficient converters of food into milk. You may think that milk production to a cow is an automatic process, which is little or not at all affected by her state of mind or her standard of intelligence, but I am convinced that the profitable utilization of food, and the efficient conversion of food into milk, requires a special kind of intelligence in the cow which places it well above the average intelligence of its species, and that this special intelligence is observable in the facial expression of the cow. For further confirmation of this theory compare the faces of beef animals with those of milk-producing animals. Getting fat doesn't require much intelligence, and the process of becoming fat has a dulling effect on the intellect. It may be a fine point, but to the successful breeder it is an important one. Further, I had to look my cows in the face every day! My next step then was to decide whether I should try to eliminate this undesirable characteristic or to concentrate upon the good factors. It was as yet too early to say whether sufficient milk had been transmitted, or whether the bull had improved on the progeny's dam's yields of milk and butterfat. As far as production transmission was concerned, I felt that given big barrels, sound legs and good udder it was safe to assume milk—and this assumption in all my breeding, buying and judging of cattle has never failed me. It is on such experience that I disagree with the milk-and-water wallahs who say that showing is a waste of time, and that it is impossible to judge a cow's productive capacity merely by looking at her.

I decided that the way to deal with the problem of eliminating the undesirable head, while at the same time retaining the good bodies, legs and udders, was to follow the old bull with his own son out of a cow with the same good body but a more attractive head.

I found that this worked perfectly. I retained and indeed fixed all the old bull's good characteristics and yet improved the quality and intelligence of the head. By this time it was clear that the old bull's first daughters were milking well enough for my requirements, had those excellent bodies, legs and udders and the butterfat was in most cases held, though in one or two cases there was a drop in butterfat. But what was clear was that they had not quite the quality of bone which is necessary in a Jersey which is to be an efficient converter of food into milk. Coarse bone always seems to need rather more flesh to cover it than fine bone, and the tendency was with these daughters of old Top Sergente to need rather more in the way of maintenance ration than I had needed for their dams—though they were all better yielders.

It is a good thing to have big-bodied, large-capacity bellies on strong legs, which are essential prerequsities of the efficient food-converting cow, but it is no use achieving that type of cow with coarse bones, for she will only want to cover them, and also use some of the valuable milk-making ingredients of her food for bone maintenance.

So I had to find an outcross which would bring quality to the bone without losing the stomach capacity—strong straight legs and shapely udders. It must, as well, be a strain that would increase the butterfat.

In my now burning enthusiasm for the Jersey cow, I had seen many herds both in the Island and in England. But one herd stood out on its own for consistency of pleasing type and butterfat. That was the Lockyers herd of John G. Bell. I went back to see that herd (after visiting others in the intervals between visits to Lockyers) so often that I came to know quite intimately many of its members, and each time I was impressed with the superiority in quality and uniformity over all other herds. The herd had been most studiously bred for over thirty years and some of the old families, two in particular, which emanated from one bull—Valentino, gave me my first real feeling of certainty regarding perfection in a Jersey. These families were founded with Lockyers Madeline and Lockyers Verbena. What they had in addition to the essential commercial and constitutional qualities which Top Sergente had given me, were a beautiful mahogany red colour, and longevity. The first, a factor which is superficially quite unimportant in the commercial dairy herd, but which influences every breeder, farmer or herdsman who loves his cows, and may even have some bearing on milk colour and fat content; the second, perhaps the most needed factor in our dairy herds to-day. So it was to the old Lockyers family that I went for bulls, and it was from the same herd, with the addition of some components from my imagination and the Top Sergente family, that I developed in my mind's eye the model of a perfect Jersey, the model which must be permanently engraved in the waking and sleeping thoughts of all keen breeders. I suppose this picture will live in my mind until one day hence in my doddering nineties I may see it grazing my pastures!

This mental picture in the heart and mind of the true breeder, is the only sound basis of genetics. And this is really what I mean when I say the genetics of animal breeding can never be learned from a book. If you haven't the ability to conjure up each time you look at a cow or a bull, the background canvas of the perfect animal against which to measure it, then you may as well decide that you had better remain a cowkeeper or a cowman only, and leave breeding and herdsmanship to those with the heart and mind for it.

There is much still to be learned about the effect of environment on breeding. Whether characteristics caused by environment can be inherited is still an open question. No book on cattle breeding gives any importance to this subject but my experience leads me to believe that acquired characteristics may be transmissible.

I was first given to consider this point when I started breeding Channel Island cattle. I soon discovered that there was a distinct island type, peculiar to animals bred on the islands. With Jerseys two characteristics were marked in animals born on the island, and the first few generations of their progeny bred away from the island. These characteristics are fine bone and the tendency to weak hocks and hind legs generally. Jerseys bred in England, with a long ancestry of English breeding have not retained such fine bone though still much finer than other breeds; neither do they have the marked tendency to 'cow hocks' which is evident in imported and early generations from imported Jerseys.

When I first went over to Jersey I found that fine bone and weak hocks were unquestionably the result of environment. The custom in the island of tying up their animals from the first few weeks of age for the rest of their lives, with little or no exercise other than being led out to tether in the summer, makes weak hocks inevitable, especially in conjunction with the so-called 'scientific starvation' which is practised to ensure fine bone.

But what struck me as remarkable, was the fact that these characteristics, particularly the weak hocks, are transmitted to their progeny bred in England and reared under perfect conditions of nutrition and exercise. I searched in vain for some mention in books on genetics of this undesirable demonstration of acquired characteristics becoming hereditary. I had previously believed that weak hocks were caused solely by faulty nutrition and lack of exercise, and that it was a factor which could not be transmitted. But there is no doubt that in this instance, at any rate, environmental conditions have changed inheritance to such an extent as to render the characteristic transmittable. In other words, we can by environment improve or harm the future inheritance of our herds. We already know that it is useless to expect breeding to overcome bad management. Because a bull whose dam has given 2,000 gallons of milk is mated to a 2,000-gallon cow it does not follow that the progeny will also give 2,000 gallons of milk at maturity. If environment is unsuitable and management is faulty, they may not give more than 200 gallons. Similarly it is probably possible by improved management and ideal environment to produce over the generations, better-yielding and more profitable cattle, and in so doing influence the inheritance of characteristics acquired by good management and the right environment.

There have been many examples of cows under identical management and apparently identical feeding showing inexplicable improvement when moved from one farm to another. I recently visited a Jersey herd which had been moved from Southern Ireland to England. Cows which had never averaged more than 600 gallons of milk suddenly, under a regime identical in every respect, even with exactly the same staff, poured out a herd average of 1,100 gallons. A similar capacity has been passed to the first daughters of these cows born and so far recorded in this country.

Though I have read none of his writings or even seen any published details of his theories, I understand that a Russian scientist, Dr. Lysenko, has founded a whole theory of genetics on the idea that qualities acquired by environment are inherited. My own knowledge of the subject is merely that of a breeder, but I do suggest that further serious investigation of the effect of environment on heredity is desirable. For instance, if the Island of Jersey authorities would admit into Jersey cattle of several generations of English breeding with strong straight legs we could see if in the course of a few generations, under the conditions which have produced weak-hocked Jerseys, they would revert to cow-hocks.

All farmers know of instances of animals which have been started well by their breeder, being sold as perfect specimens of their breed, only to go back under bad management and appear later at any rate, to be thoroughly poor specimens of the breed and under the same bad environments to breed animals which appear to have inherited the characteristics created by the bad management of the dam.

Yet without knowledge of these environmental factors it would be impossible to say whether the poor specimen was the result of heredity or the effect of management of the dam before and during pregnancy. The desirable qualities of bone and horn structure in the Scottish Blackface ram can be produced artificially by suckling the young tup on a goat. The buyer believes he has found a ram with outstanding inheritance and pays an exaggerated price only to find that these qualities are not transmitted to their progeny, having been acquired in the ram purely by virtue of the greater milking capacity and richer milk of his goat foster-mother.

But would it be possible by repeating this system of ram rearing for generations to develop the ability to transmit improved bone and horns? I really don't know, and I don't know anyone who has pursued the subject long enough to find out. There is a good deal of evidence either way and I am certainly not qualified to do more than instance the above illustrations from my very limited and unscientific observations as a practical breeder.

Chapter 4

HERD EFFICIENCY

Sources of Increased Profitability

Most breeders of pedigree cattle have reached a stage in their progress towards maximum milk yields when further increases can be achieved only at the expense of the health of the animal. I believe that Breed Societies which continue to encourage the extraction of ever higher yields are merely laying the foundations of the extinction of their breeds. Sooner or later the constitution of the best milking cows will suffer and the weakness will be transmitted in ever increasing concentrations until large sections of the breed become sterile. There is bound to be a limit to the transmission of the ability to produce freak yields, particularly as the wherewithal of high milk yields and health, that is properly grown food, is slowly diminishing.

If a limit is to be set on higher yields, what, in the face of seemingly endless increases in costs are we to do to keep income ahead of expenditure?

There are, in my opinion, three practically untapped sources of saving: (1) Improved health in the herd. (2) Increased production efficiency, i.e. to breed for a better efficiency in the cow's ability to convert food into milk. (3) To breed for longevity. These are all sources of increased income or economy which have been largely ignored in our efforts to get more and more milk to the almost complete exclusion of any other policy.

We hear various figures from £50 million to £250 million a year quoted as the cost of disease to the dairy farmers of this country. If the figure is somewhere between the two it means that each dairy farmer in this country could be handed something like £1,000 a year if cattle diseases cost the nation nothing, without taking any account whatever of the increased income which a disease-free herd could bring to the dairy farmer.

Cattle disease is not inevitable as I have shown in my own herd, simply by adopting the commonsense organic methods described in Fertility Farming. The sooner the authorities accept the challenge made towards the end of this book and investigate such methods, the sooner will disease be eliminated. I expect my cows to do an average of 10 or 12 lactations with no mastitis, no sterility and no abortion and the same is possible for any farmer prepared to adopt similar methods.

Food conversion efficiency is to some extent dependent on breed. A breed which carries flesh as well as milk always draws a proportion of its food for its own body covering—and a large frame needs a larger proportion of food to maintain it than a small one. But within all breeds it is possible to select strains which are more economical converters of food into milk. The time has come for us to measure the ability of a cow, not by the quantity of milk or butterfat she gives, regardless of all other factors, but by a unit of assessment which takes account of milk total solids production in relation to body weight and food consumed. Present-day milk recording is already obsolete. A system of recording which measures cost per gallon per cwt. of body weight gives me the only true guide to profitable milk production. Such a system provided for me the information which decided me first, when I was costing three different breeds in my herd, to discard the two uneconomical breeds and concentrate on that which produced milk at the lowest cost per gallon, and second, to give up almost entirely, feeding concentrates of any kind when I found that the yield given on grass and silage was far more profitable.

Longevity, though perhaps the most important factor of all, takes longer to achieve in our policy of breeding. But if we are to farm well we must breed for longevity as well as for health and production efficiency. Fortunately longevity is often a result of the fertility farming methods about which I have written. Every farmer, if he has a good cow, wants to keep it as long as possible. So we must select good cows but good old ones are a better breeding bet than good young ones.

I own the oldest living pedigree cow—Lockyers Verbena, now 22 years old—and a grandson of hers who is also a grandson of her 18-years-old sister, both great total lifetime yielders as well as show winners. This is the breeding upon which I am concentrating. This is the blood we should all look for and concentrate in our herds.

Costs of production would then automatically fall and wastage from disease and death would be reduced to a minimum.

An excellent demonstration of the importance of milk production efficiency as distinct from merely high yields is provided by a comparison of the moderate yielding Isfield Jersey herd of Mr. F. J. Rigby. The tables on pages 44 and 45 show first an analysis of the milk production costs of this highly efficient Jersey herd and these costs are set alongside comparative figures for the Royal Agricultural College herds. Professor Boutflour and his deputy, Kenneth Russell, have achieved considerable fame for their methods of dairy herd management, much of which is highly creditable. Their herds have come to be regarded as the criterion of efficiency. They have put all intelligent dairy farmers on their toes and given us a measure against which to test our own herd achievements. The fact that I, and others, disagree with some of the methods employed to achieve the Royal Agricultural College results is beside the point. Whatever the methods employed, dairy farming profitability demands comparisons by final results in relation to the cost of achieving them, both in judging our methods and in choosing our breeds. Mr. Rigby has shown that a moderate yielding cow which is an efficient converter can with comparatively natural methods, emulate even the achievements of the Royal Agricultural College in profitability.

A farming friend of mine in the north is keeping about 500 cattle as well as many other animals on about 900 acres, and feeding them off the farm. I tried to persuade him to keep fewer and better cattle but he would have none of it. His theory was that if he kept valuable pedigree cattle they would only be ruined by incompetent men. Pedigree cows or reasonably high producers of any kind, he said, were only for the man who could give personal attention to his herd and thus avoid the higher loss which would result if careless treatment lost a cow.

He works on the principle that if he can get only mediocre herdsmen, then it is more profitable to attain his required milk output from large numbers instead of high-producing animals in smaller numbers. Having got his large herd he feeds them almost entirely on bulky food; gets a herd average of about 500 gallons and no disease. With herds of 250 cows in milk he has no vet's bill. He does not even produce T.T. milk so there are no charges for tests and no elaborate efforts to produce ultra-clean milk with the attendant high costs. No purchased foodstuffs, no vet's bill, no fuel bill for sterilizing utensils, no losses from disease, not even temporary infertility! I must say that though the whole of my training and instinct rebels at the idea, it does seem to work. He maintains that 250 cows averaging 500 gallons pay him better than 125 cows averaging 1,000 gallons with all the attendant troubles which are inevitable in a 1,000-gallon average herd. And the extra quantity of farmyard manure produced well repays, he claims, the cost of feeding his extra 125 cows to get the same amount of milk.

When I first looked into this friend's methods I couldn't make up my mind whether this was mass production of muck and milk which was also a sound proposition as a money producer, or whether it was just inefficient old-fashioned farming. But if it was inefficient farming, I decided, it was certainly scientific inefficiency and only careful costings will provide the right answer from the financial angle.

Unfortunately my friend points to farms where testings, recordings, costings, pedigree registering and all that paper performance associated with an attested pedigree herd, are far more costly than the value of the information they produce. So he is content to enjoy what many super-efficient farmers never see, profit in every pail of milk, without spending it all and more in finding how it got there.

There is no doubt that we have reached a stage in our milk production when the hygiene ritual is costing more than it is worth, and where much of our most costly effort in the direction of increased yield and 'improved' disease control is merely adding far more to our problems.

Vaccination against contagious abortion, for instance, about which the veterinary profession has been so confident, is now coming unstuck. Several herd owners, some well known, have already admitted that in spite of many years of vaccination with S.19 they are now experiencing a series of abortions which have no apparent explanation.

The Farmers' Weekly reported, on 26th October 1951, that its own herd which has been vaccinated with S.19 for many years, nevertheless had six abortions in succession for which no veterinary authority had been able to find an explanation. The following report appeared in The Editor's Diary: 'We have all been concerned over the outbreak of infertility and abortion, yet there is nothing like a little trouble at home to make one realize just how difficult a subject it is and how little is really known about it.

"A disturbance of the normal breeding cycle in our own herd at Grove Farm has brought us face to face with a trouble as puzzling as it is sudden. Previously, we have had no serious difficulty, and we have always had our stock vaccinated with S.19.

† Appreciation.

YEAR ENDED 1ST OCTOBER 1950 IN A MILK COSTS

INVESTIGATION BY WYE COLLEGE

Group

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Newhouse Farm Isfield --F.J.Rigby

(per gallon)Under

to

20.99d21.00d

to

22.99d23.00d

to

24.99d25.00d

to

26.99d27.00d

to

28.99d29.00d

and

over

No. of Farms

11

4

11

19

3

11

Average No. of cows per herd

31.0

28.6

33.0

24.3

29.0

27.0

74.5

Average yield per cow--gals.

779

791

717

687

806

663

645

Per-cent yield:

Winter

Summer48.60

51.4049.50

50.5049.04

50.9648.53

51.4751.85

48.1549.57

50.4340.81

59.19

Per cent cows

dry21.4

19.4

17.4

19.6

16.8

16.4

19.0

Cost per gallon:

Purch. foods

Home-grown

hay, etd

Grazingd.

6.89

4.03

1.76d.

4.30

5.56

1.22d.

6.64

6.58

1.39d.

6.15

6.62

2.12d.

8.04

5.54

2.16d.

5.98

9.28

2.49d.

3.89

4.22

2.15

Total Foods

less F.Y.M.12.68

0.2511.08

0.2214.61

0.2414.89

0.3215.74

0.3217.75

0.2810.26

0.22

Net cost of foods

Labour

Depreciation on

cows

Sundries12.43

5.32

0.35†

2.9210.86

7.56

0.21†

3.6514.37

6.01

0.15†

3.5514.57

6.36

0.82

4.3415.42

6.53

0.92

4.7117.47

9.36

0.09

5.2710.04

5.68†

0.42

3.22

Net cost per gal.

22.32

21.86

23.78

26.09

27.58

32.19

18.52

Net cost per cow

£

66.0£

72.1£

71.0£

74.7£

92.7£

88.9£

49.8

Note: All figures are weighted averages. No allowance has been made for: (a) delivery costs of any kind; (b) interest on capital; (c) managerial salary.

The Isfield Jersey herd sold 645 gallons per cow, sold at 4s. 6d. per gallon (farm-bottled, wholesale) = £145 2s. 6d. Net cost per cow = £49 16s. Showing a margin per cow of £95 6s. 6d., excluding items (a), (b) and (c).

PROFESSOR BOUTFLOUR'S HERDS: STEADINGS AND

FOSSEHILL, CIRENCESTER 1949

COMPARED WITH ISFIELD PEDIGREE JERSEYS HERD

Management

Steadings

IntensiveFosse Hill

ExtensiveIsfield

Extensive

Size of farm

64 acres

160 acres

287 acres

Size of herd

19 cows

38 cows

74-1/2 cows

Breed

Friesian

Ayrshire

Jersey

System

Shed and Hand Milking

Yards and Parlour

Shed, Yards and Parlour

Gross sale, milk

1,090 gallons

£147 per cow660 gallons

£96 per cow645 gallons

£147 per cow

Gross cost, milk

£74 10 0

£58

£49 16 0

Food, home-grown

Graze

Purchased

Total £ s. d.

22 18 0

6 10 0

14 2 0

43 0 0 £ s. d.

19 4 0

6 9 0

7 14 0

33 0 0£ s. d.

11 7 0

5 15 6

10 9 0

27 11 6

Labour total

Misc. and Depreciation£24

£7 10 0£12 8 0

£12 12 0£15 5 0

£8 7 0

Profit margin per cow

£72 10 0

£38 0 0

£95 6 6

Returns per £100 food cost

£340 0 0

£310 0 0

£540 0 0

Returns per £100 labour

£650 0 0

£777 0 0

£1,080 0 0

Returns per £100 cow capital

£210 0 0

£160 0 0

£145 0 0

Steadings and Fosse Hill herds are T.T. attested, in process of grading up.

Isfield herd is full pedigree island foundation stock, T.T. attested, closed herd.

The Isfield production is sold to Uckfield Dairies Limited (same owner as the herd) at farm-bottled standard price.

The Isfield herd and Steadings have identical cash sales of £147 each, Steadings with 1,090 gallons, Isfield with 645 gallons only per cow.

'The blow came when six autumn cows in succession either aborted within a period of up to one month, or produced dead calves at the normal time. In all these cases the calves appeared fully formed, and there were no obvious symptoms of abnormality either before or after calving.

'After a negative blood test, we ruled out contagious abortion. Other infectious causes, such as trichamoniasas and vibrio foetus, were already eliminated for obvious reasons. This left three other possibilities—heredity (eliminated in our case on the analysis of the pedigree), some unknown deficiency or—less likely—poison.

'Fortunately, subsequent calvings have been normal, and there is some comfort anyway in the fact that the earlier calvings were predominantly bull calves. We are also managing to get some milk out of the affected cows, so that they are not a complete loss.

'Nevertheless, the trouble is a serious one and both the veterinary profession and we want to get to the bottom of it. It would be interesting and helpful to hear of any similar trouble occurring on other farms."

The explanation to me seems obvious. S.19 was given the credit for a respite from abortion which follows an outbreak in any herd. The act of abortion is itself a curative process, without which an animal managed by orthodox methods would otherwise become sterile. The only permanent preventive of abortion, or any other cattle disease for that matter, is a complete revolution in management which necessitates a natural nutrition, of the soil, the calf and the cow, in that order of importance: If the soil is healthy, all the animals on the farm have a better chance of health through the home-grown food which I believe to be an essential to proper health. If the calf is naturally fed then the chances of a healthy cowhood are made safe. Then, assuming we still insist on over-exploiting the cow she has a better chance of surviving our treatment. But to expect a cow to withstand modern milk production on unnatural food without the health foundations of a reasonably natural calfhood is asking too much.

Chapter 5

A CALL FOR SOME CATTLE-SALE REFORMS

and a Formula for Future Sales

Though average prices of pedigree cattle to-day are settling down to a reasonable level, record prices are still being made for all breeds of pedigree cattle; buyers have apparently never been so keen to pay for good stock, and yet it still needs a brave man to gamble his money in the pedigree saleyard.

For gamble indeed it is in many cases. Any man who has bought stock at collective sales of pedigree cattle in recent years will speak with deep feeling when the subjects of udder warranties, tuberculin tests, and shy breeding are mentioned.

In spite of modern safeguards and the admirable trend of some pioneers towards the frank catalogue, I am not alone when I say that I always experienced a weakness about the knees for some days after a purchase at a pedigree sale. Snags are still far more common than pleasant surprises when the new cow is put to a working test at home.

The so-called udder warranty is perhaps the greatest culprit. Some of my own experiences in buying illustrate the anomalies of present sale rules in this respect and will, I hope, show how the udder warranty conditions could give a fairer deal to the buyer without bringing any hardship on the reputable vendor.

I have bought cows with udders and teats warranted sound, but which have not survived the journey home in good order.

Against this there is no protection and apparently no possibility of redress.

The rules of several breed societies contain a clause requiring a guarantee that any cow in-calf or in-milk, or any heifer in-milk, is sound in udder and teats at the time of sale, but admitting no claim in respect thereof which is not made within one hour of the close of the sale.

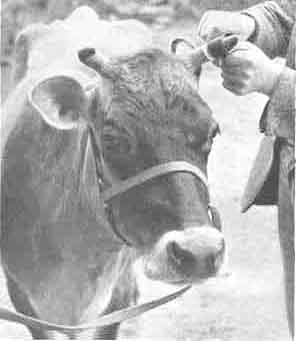

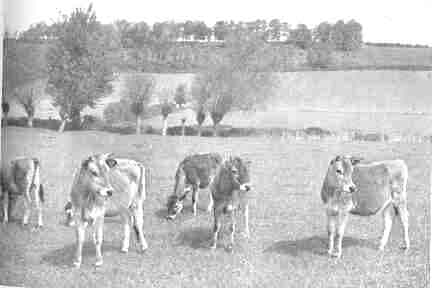

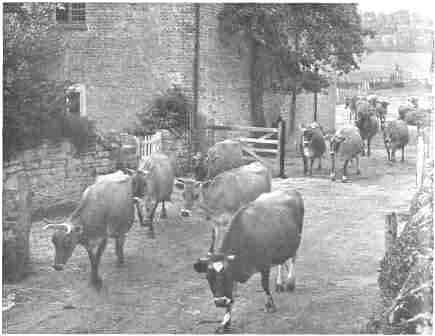

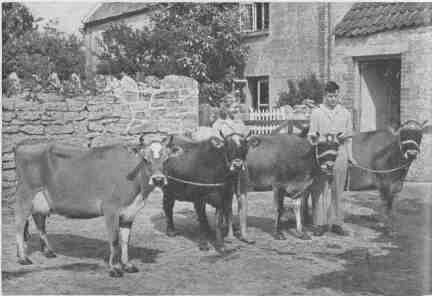

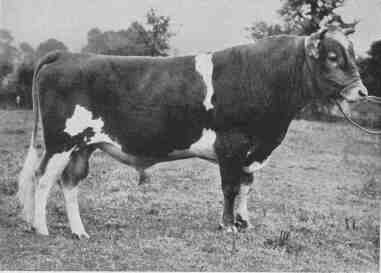

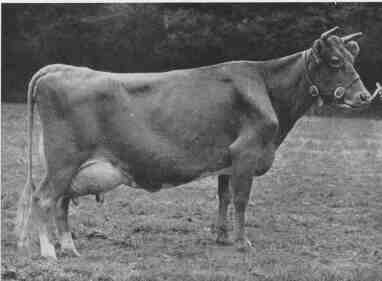

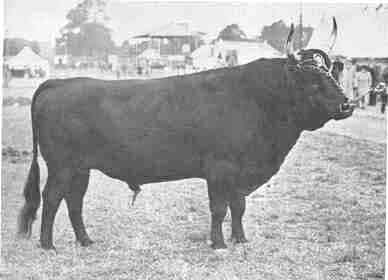

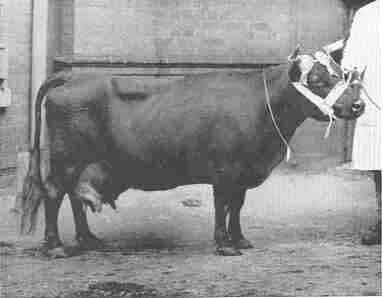

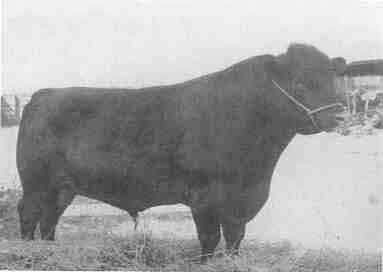

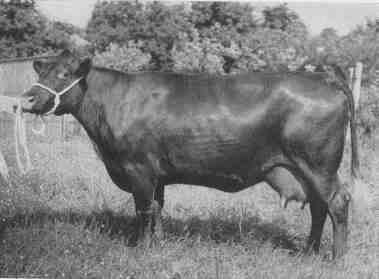

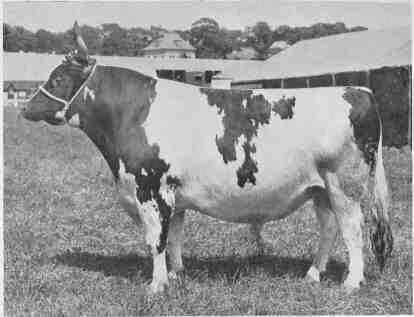

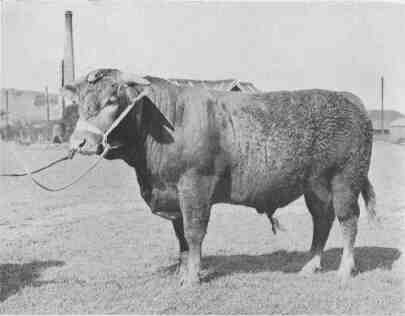

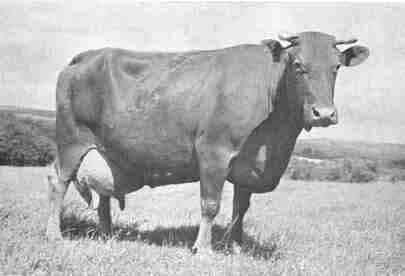

1. Coming in for milking. S. Mayall's Pimhill herd which is managed on lines advocated by the author

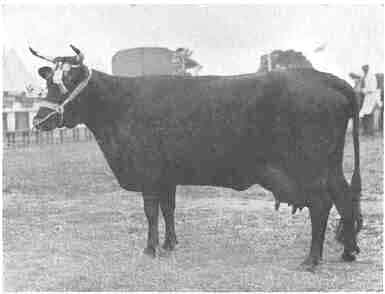

2. Long-lived families which have bred consistently are the best source of foundation stock. Five generations in the Ayrshire herd of S. Mayall. Pimhill Sarah heads a family line

To expect anyone to give a sound judgment on the condition of an udder that has been stocked for eighteen hours, in the harassing conditions of the average saleyard is, of course, fantastic. The cow must be got home and given at least two milkings before she can fairly be judged in the udder.

I have closely examined the udders of cows I was intending to buy. Where there has been only slight suspicion of thickening in the milk passage, or a little lightness in one quarter, and I have particularly liked the cow, I have taken the risk.

In any case, I was then experimenting on my treatment for mastitis and was satisfied that I could cure them if they did go wrong.

Surely enough, some have gone wrong. I have had cows with a suspicion of thickening in the udder before the sale, but which, confident in the udder warranty, I have purchased, only to find them giving filthy milk at the first milking on arrival home. Others that I suspected to be slightly light in one quarter, have gone wrong in that quarter within a few days of arrival home.

That I was able to treat them does not alter the fact that such cases do not give a square deal to the buyer. For cost of treatment is not anticipated in the purchase of expensive pedigree cattle.

Expert examination has sometimes revealed obvious cases of longstanding mastitis which had presumably been treated and rendered temporarily ineffective. The trouble remained dormant only to break out under the strain of stocking the udder, followed by a long train journey.

Where complaints have been made immediately the cattle were home, the auctioneers naturally reminded me of the 'conditions of sale'. The reputation of vendors proves to be no safeguard. When complaints are passed to them, they merely need affirm that the udders were sound when they left the farm or the saleyard, and their responsibility is ended, unless legal action is taken and misrepresentation proved.

What is the buyer to do in such a case? It is surely wrong that all the burden of such a loss should be on the unfortunate buyer, who, in such cases, cannot possibly have any part in the causation of the udder trouble.

Conditions of sale ruling at most auctions to-day encourage the breeder to use them for the disposal of his duds. If the cattle can survive the hour after the sale the vendor has succeeded in passing his dud and the buyer has no redress. If the buyer were allowed to have the cow on his farm for just one day there would be reasonable time to give the udder a working test and place the blame for any defect where it rightly belongs.

Complaints arising from such a procedure would react unfavourably only on the habitual seller of unsound udders. For udders do not suddenly become rotten with mastitis overnight. Any outbreak of mastitis within twenty-four hours of a sale is certain to have existed in the udder at the time of, or before the sale. It is therefore reasonable that the seller, not the buyer, should be the loser, or at least share the loss.

In any case most mastitis is of deeper seated origin than the mere mechanical infection by external bacteria, and cases such as I have described are almost certain to be the result of previous bad management, or breeding which has predisposed the animal to mastitis.

Many young farmers are starting new pedigree herds at the present time and breed societies would do well to turn their attention to the satisfaction of these newcomers, instead of watching mainly the interests of their council members who are normally all established vendors themselves.