Isolated and modernized Gaelics

STORIES have long been told of the superb health of the people living in the Islands of the Outer Hebrides. The smoke oozing through the thatched roofs of their "black houses" has added weirdness to the description of their home life and strange environment. These stories have included a description of their wonderfully fine teeth and their stalwart physiques and strong characters. They, accordingly, provide an excellent setting for a study to throw light on the problem of the cause of dental caries and modern physical degeneration. These Islands lie off the northwest coast of Scotland, extending to a latitude nearly as far north as the southern part of Greenland. A typical view of their thatched-roof cottages may be seen in Fig. 5.

The Isle of Lewis has a population of about twenty thousand, made up almost entirely of fisher folk and crofters or sheep raisers. This island has so little lime in its soil that it is said that there are no trees in the entire island except a few which have been planted. The surface of the island is largely covered with peat, varying in thickness from a few inches to twenty feet. This is the fuel. Peat contains the rootlets of the plant life which grew many centuries ago. There is so little bacterial growth that vegetable products undergo very slow decay. The pasturage of the island is so poor that exceedingly few cattle are to be found, largely because they do not properly mature and reproduce. In a few districts some highland cattle with long shaggy hair and wide spread horns are found. Almost all of these are imported. The principal herd of cattle on the island consists of a few dozen head on the government experimental farm.

The basic foods of these islanders are fish and oat products with a little barley. Oat grain is the one cereal which develops fairly readily, and it provides the porridge and oat cakes which in many homes are eaten in some form regularly with each meal. The fishing about the Outer Hebrides is specially favorable, and small sea foods, including lobsters, crabs, oysters and clams, are abundant. An important and highly relished article of diet has been baked cod's head stuffed with chopped cod's liver and oatmeal. The principal port of the Isle of Lewis is Stornoway with a fixed population of about four thousand and a floating population of seamen over week-ends, of an equal or greater number. The Sunday we spent there, 450 large fishing boats were said to be in the port for the week-end. Large quantities of fish are packed here for foreign markets. These hardy fisherwomen often toil from six in the morning to ten at night. The abundance of fish makes the cost of living very low.

In Fig. 5 may be seen three of these fisher-people with teeth of unusual perfection. We saw them at the fish-cleaning benches from early morning till late at night dressed, as you see them pictured, in their oilskin suits and rubber boots. We met them again in their Sunday attire taking important parts in the leading church. It would be difficult to find examples of womanhood combining a higher degree of physical perfection and more exalted ideals than these weather-hardened toilers. Theirs is a land of frequent gales, often sleet-ridden or enshrouded in penetrating cold fogs. Life is full of meaning for characters that are developed to accept as everyday routine raging seas and piercing blizzards representing the accumulated fury of the treacherous north Atlantic. One marvels at their gentleness, refinement and sweetness of character.

The people live in these so-called black houses. These are thatched-roof dwellings containing usually two or three rooms. The walls are built of stone and dirt, ordinarily about five feet in thickness. There is usually a fireplace and chimney, one or two outside doors, and very few windows in the house. The thatch of the roofs plays a very important rôle. It is replaced each October and the old thatch is believed by the natives to have great value as a special fertilizer for their soil because of its impregnation with chemicals that have been obtained from the peat smoke which may be seen seeping through all parts of the roof at all seasons of the year. Peat fires are kept burning for this explicit purpose even when the heat is not needed. This means that enormous quantities of peat are required to maintain a continuous smudge. Some of the houses have no chimney because it is desirable that the smoke leave the building through the thatched roof. Not infrequently smoke is seen rolling out of an open door or open window. Fortunately the peat is so abundant that it can be obtained easily from the almost limitless quantities nearby. The sheep that roam the heather-covered plains are of a small black-faced breed, exhibiting great hardihood. They provide wool of specially high quality, which, incidentally, is the source of the famous Harris Tweeds which are woven in these small black houses chiefly on the Isle of Harris.

We are particularly concerned with the people of early Scotch descent who possess a physique that rivals that found in almost any place in the world. They are descendants of the original Gaelic stock which is their language today, and the only one which a large percentage of them can speak. This island has only one port which means that most of the shore line still provides primitive living conditions as does the central part of the island. It was a great surprise, and indeed a very happy one, to find such high types of manhood and womanhood as exist among the occupants of these rustic thatched-roof homes, usually located in an expanse of heather-covered treeless plains. It would be hard to visualize a more complete isolation for child life than many of these homes provide, and one marvels at the refinement, intelligence, and strength of character of these rugged people. They resent, and I think justly so, the critical and uncomplimentary references made to their homes in attaching to them the name "black-houses." Several that we visited were artistically decorated with clean wallpaper and improvised hangings.

One would expect that in their one seaport town of Stornoway things would be gay over the week-end, if not boisterous, with between four and five thousand fishermen and seamen on shore-leave from Saturday until midnight Sunday. On Saturday evening the sidewalks were crowded with happy carefree people, but no boisterousness and no drinking were to be seen. Sunday the people went in throngs to their various churches. Before the sailors went aboard their crafts on Sunday evening they met in bands on the street and on the piers for religious singing and prayers for safety on their next fishing expedition. One could not buy a postage stamp, a picture card, or a newspaper, could not hire a taxi, and could not find a place of amusement open on Sunday. Everybody has reverence for the Sabbath day on the Isle of Lewis. Every activity is made subservient to their observance of the Sabbath day. In few places in the world are moral standards so high. One wonders if the bleak winds which thrash the north Atlantic from our Labrador and Greenland coasts have not tempered the souls of these people and created in them higher levels of nobility and exalted human expression. These people are the outposts of the western fringe of the European continent.

Just as one sees in Brittany, on the west coast of France, the prehistoric druidical stone forest marking a civilization which existed so far in the past as to be without historic records except in its monuments; so, too, we find here the forest of granite slabs in which these sturdy prehistoric souls worshipped their divinities before they were crowded into the sea by the westward moving hordes. When one realizes the distance that these heavy stones had to be transported, a distance of probably twenty miles over difficult terrain, we can appreciate the task. Their size can be calculated from the depth to which they must be buried in order to stand erect even to this day.

We are concerned primarily with the physical development of the people, and particularly with their freedom from dental caries or tooth decay. One has only to see them carrying their burdens of peat or to observe the ease with which the fisherwomen on the docks carry their tubs of fish back from the cleaning table to the tiers of packing barrels to be convinced that these people have not only been trained to work, but have physiques equal to the task. These studies included the making of dental examinations, the taking of photographs, the obtaining of samples of saliva for chemical analysis, the gathering of detailed clinical records, and the collecting of samples of food for chemical analysis and detailed nutritional data.

Communication is very difficult among many of these islands. It would be difficult to find more complete isolation than some of them afford. We tried to get to the islands of Taransay and Scarpa on the west coast of the Isle of Harris, but were unable to obtain transportation since the trip can be made only in special, seaworthy crafts, which will undertake the passage only at certain phases of the tide and at certain directions of the winds. On one of these islands, we were told, the growing boys and girls had exceedingly high immunity to tooth decay. Their isolation was so great that a young woman of about twenty years of age who came to the Isle of Harris from Taransay Island had never seen milk in any larger quantity than drops. There are no dairy animals on that island. Their nutrition is provided by their oat products and fish, and by a very limited amount of vegetable foods. Lobsters and flat fish are a very important part of their foods. Fruits are practically unknown. Yet the physiques of these people are remarkably fine.

It was necessary sometimes for us to engage skilled seamen and their crafts to make a special trip to some of these isolated islands. These seamen watch critically the tide, wind and sky, and determine the length of time it will be safe to travel in a certain direction under conditions existing in the speed of the running tide and the periodic change of the wind. Some of the islands are isolated by severe weather conditions for many months of the year.

These islands have been important in the whaling industry, even up to recent years. We visited a whaling station on the Isle of Harris, not active at this time, where monsters of the sea were towed into a deep bay.

In the interior of the Isle of Lewis the teeth of the growing boys and girls had a very high degree of perfection, with only 1.3 teeth out of every hundred examined that had even been attacked by dental caries.

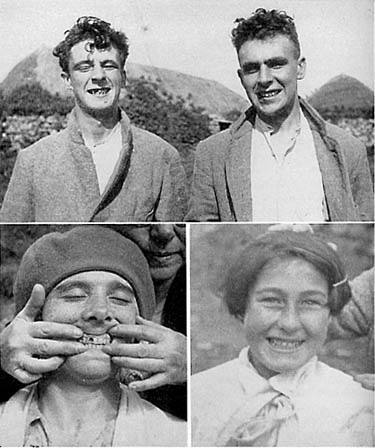

An important part of the study of these islands was the observations made on conditions at the fringe of civilization. A typical cross-section of the residents of the seaport town of Stornoway can be seen assembled on the docks to greet the arrival of the evening boat, the principal event of the community. The group consists largely of adult young people. In a count of one hundred individuals appearing to be between the ages of twenty and forty, twenty-five were already wearing artificial teeth, and as many more would have been more presentable had they too been so equipped. Dental caries was very extensive in the modernized section of Stornoway. Since an important part of these studies involved a determination of the kinds and quantities of foods eaten, it was necessary to visit the sources available for purchasing foods in each town studied. In Stornoway, one could purchase angel food cake, white bread, as snow white as that to be found in any community in the world, many other white-flour products; also, canned marmalades, canned vegetables, sweetened fruit juices, jams, confections of every type filled the store windows and counters. These foods probably made a great appeal both because of their variety and their high sugar content to the pallets of these primitive people. The difference in physical appearance of the child life of Stornoway from that of the interior of the Isle of Lewis was striking. We found a family on the opposite coast of the island where the two boys shown in the upper half of Fig. 6 resided. One had excellent teeth and the other had rampant caries. These boys were brothers eating at the same table. The older boy, with excellent teeth, was still enjoying primitive food of oatmeal and oatcake and sea foods with some limited dairy products. The younger boy, seen to the left, had extensive tooth decay. Many teeth were missing including two in the front. He insisted on having white bread, jam, highly sweetened coffee and also sweet chocolates. His father told me with deep concern how difficult it was for this boy to get up in the morning and go to work.

One of the sad stories of the Isle of Lewis has to do with the recent rapid progress of the white plague. The younger generation of the modernized part of the Isle of Lewis is not showing the same resistance to tuberculosis as their ancestors. Indeed a special hospital has been built at Stornoway for the rapidly increasing number of tubercular patients, particularly for girls between twenty and thirty years of age. The superintendent told me with deep concern of the rapidity with which this menace is growing. Apparently very little consideration was being given to the change in nutrition as a possible explanation for the failure of this generation to show the defense of previous generations against pulmonary tuberculosis. In this connection much blame had been placed upon the housing conditions, it being thought that the thatched-roof house with its smoke-laden air was an important contributing factor, notwithstanding the fact that former generations had been free from the disease. I was told that the incidence of tuberculosis was frequently the same in the modern homes as it was in the thatched-roof homes. It was of special interest to observe the mental attitude of the native with regard to the thatched-roof house. Again and again, we saw the new house built beside the old one, and the people apparently living in the new one, but still keeping the smoke smudging through the thatch of the old thatched-roof house. When I inquired regarding this I was told by one of the clearthinking residents that this thatch collected something from the smoke which when put in the soil doubled the growth of plants and yield of grain. He showed me with keen interest two patches of grain which seemed to demonstrate the soundness of his contention.

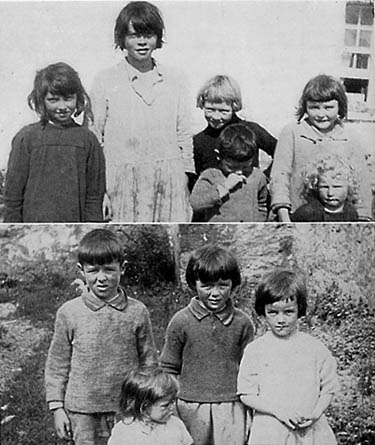

I was particularly interested in studying the growing boys and girls at a place called Scalpay in the Isle of Harris. This Island is very rocky and has only small patches of soil for available pasturage. For nutrition, the children of this community were dependent very largely on oatmeal porridge, oatcake and sea foods. An examination of the growing boys and girls disclosed the fact that only one tooth out of every hundred examined had ever been attacked by tooth decay. The general physical development of these children was excellent, as may be seen in the upper half of Fig. 7. Note their broad faces.

This is in striking contrast with the children of the hamlet of Tarbert which is the only shipping port on the Isle of Harris, and the place of export of most of the famous Harris tweeds which are manufactured on looms in the various crofters' homes. These Tarbert children had an incidence of 32.4 carious teeth out of every hundred teeth examined. The distance between these two points is not over ten miles and both have equal facilities for obtaining sea foods, being on the coast. Only the latter, however, has access to modern foods, since it supports a white bread bakery store with modern jams, marmalades, and other kinds of canned foods. In studying the tragedy of the rampant tooth decay in the mouth of a young man, I asked him regarding his plans and he stated that he was expecting to go to Stornoway about sixty miles away in the near future, where there was a dentist, and have all his teeth extracted and plates made. He said that it was no use to have any teeth filled, that he would have to lose them anyway since that was everybody's experience in Tarbert. The young women were in just as poor a condition.

Through the department of dental inspection for north Scotland, I learned of a place on the Isle of Skye, Airth of Sleat, in which only a few years ago there were thirty-six children in the school, and not one case of dental caries in the group. My examination of the children in this community disclosed two groups, one living exclusively on modern foods, and the other on primitive foods. Those living on primitive foods had only 0.7 carious teeth per hundred, while those in the group living on modern foods had 16.3, or twenty-three times as many.

This community living near the sea had recently been connected with the outside world by daily steamboat service which delivered to the people modern foods of various kinds, and within this community a modern bakery, and a supply house for purchasing the canned vegetables, jams and marmalades had been established. This district was just in the process of being modernized.

I examined teeth of several people in the seventies and eighties, and except for gingival infections with some loosening of the teeth, nearly all of the teeth were present and there was very little evidence that dental caries had ever existed. The elderly people were bemoaning the fact that the generation that was growing up had not the health of former generations. I asked what their explanation was and they pointed to two stone grinding mills which they said had ground the oats for oatcake and porridge for their families and preceding families for hundreds of years. Though they prized them highly, the plea that they would be helpful in educational work in America induced them to sell the mills to me. They told us with great concern of the recent rapid decline in health of the young people of this district.

This one-time well-populated Island, the misty Isle of Skye, still has one of the finest of the famous old castles, that belonging to the Dunvegan clan. It participated in the romantic life of Prince Charlie. The castle equipment still boasts the grandeur of a past glory. Among the relics is a horn which measured the draft to be drunk by a prospective chieftain before he could aspire to the leadership of the clan. He must drink its contents of two quarts without stopping. Again the character of that manhood is reflected in the fact that although a bounty of thirty thousand pounds was placed upon the head of Prince Charlie, none of the many who knew his place of hiding betrayed it.

On my return from the Outer Hebrides to Scotland, I was concerned to obtain information from government officials relative to the incidence of tooth decay and the degenerative diseases in various parts of north Scotland. I was advised that in the last fifty years the average height of Scotch men in some parts decreased four inches, and that this had been coincident with the general change from high immunity to dental caries to a loss of immunity in a great part of this general district. A study of the market places revealed that a large part of the nutrition was shipped into the district in the form of refined flours and canned goods and sugar. There were very few herds of dairy cattle to be seen. It was explained that even the highland cattle did not do as well as formerly on the same ranges.

As one proceeds from the north of Scotland southward to England and Wales, there is a marked increase in the percentage of individuals wearing artificial restorations or in need of them. In several communities this reached fifty per cent of adults over thirty years of age. An effort was made to find primitive people in the high country of Wales, but without success. We were advised that about the only place that we would be likely to find people living under primitive conditions would be on the Island of Bardsey off the northwest coast of Wales. This is a rock and storm-bound island with the decadent walls of an old castle and a community made up largely of recently imported colonists whom we were advised had been taken to the Island to re-populate it. There is considerable good farm land, but very limited grazing stock. Formerly the Island had produced the foods for its inhabitants with the assistance of the sea. These sources of natural foods have been largely displaced with imported white flour, marmalades, sugar, jams and canned goods. We found the physical condition of the people very poor, particularly that of the growing boys and girls. Tooth decay was so wide-spread that 27.6 out of every hundred teeth examined in the growing boys and girls had already been attacked by dental caries. It was even active in three year olds. From a conference with the director of public health of this district I learned that tuberculosis constituted a very great problem, not only for the people on this island, but for those of many districts of northern Wales. This was ascribed to the lowered defense of the people due to causes unknown. It had been noted that individuals with rampant tooth decay were more susceptible to pulmonary tuberculosis.

While on the Island of Bardsey, I inquired as to what they thought was the cause of such extensive tooth decay as we found, and was told that they were familiar with the cause and that it was due to close contact with the salt water and salt air. When I asked why many of the old people who had lived by the sea all their lives in some districts still had practically all their teeth and had never had tooth decay, no explanation was available. This they said was the reason that had been given in answer to their inquiries.

There is a very remarkable history written in the ruins of the island, and in the faces of the people who live on the Island of Bardsey. The rugged walls of ancient castles bespeak the glory and power of the people who lived proudly in past centuries. They are testified to also by the monuments in the cemeteries; but a new era has come to this island. The director of public health, of this district of Wales, including Bardsey Island, told me the story of the decline and almost complete extinction of the population due to tuberculosis. He also told how the government had re-populated the Island with fifty healthy young families, and then the sad story of how these new settlers were breaking down as rapidly as the former occupants.

The lower photograph in Fig. 7 is of a family of four children in whose faces the tragic story is deeply written. Everyone is a mouth breather and everyone has rampant tooth decay. These people are products of modernization on this island which one time produced vigorous children and stalwart men and women. It is important to compare the faces of the children of the Isle of Bardsey shown in Fig. 7 below with those shown in Fig. 7 above living in an isolated district in the Isle of Harris. As we will see later, the facial deformity does not reach its maximum severity until the eruption of the second dentition and the development of the adult face, usually at from nine to fourteen years of age. In cases of extreme injury, however, we find it appearing in the childhood face during the period of temporary or deciduous dentition. These children will, doubtless, be much more seriously deformed when their permanent dentitions and adult faces develop. It is important for us to keep this picture in mind in its relation to the high incidence of tuberculosis as we read succeeding chapters and find the part played by modernization in breaking down the defense of individuals to infective processes including tuberculosis.

In Fig. 6 (lower left) is a young girl from the Isle of Bardsey. She is about seventeen years of age. Her teeth were wrecked with dental caries, the disease involving even the front teeth. We ate a meal at the home in which she was living. It consisted of white bread, butter and jam, all imported to the island. This is in striking contrast with the picture of the girl shown in Fig. 6 (lower right) living in the Isle of Lewis, in the central area. She has splendidly formed dental arches and a high immunity to tooth decay. Her diet and that of her parents was oatmeal porridge and oatcake and fish which built stalwart people. The change in the two generations was illustrated by a little girl and her grandfather on the Isle of Skye. He was the product of the old régime, and about eighty years of age. He was carrying the harvest from the fields on his back when I stopped him to take his picture. He was typical of the stalwart product raised on the native foods. His granddaughter had pinched nostrils and narrowed face. Her dental arches were deformed and her teeth crowded. She was a mouth breather. She had the typical expression of the result of modernization after the parents had adopted the modern foods of commerce, and abandoned the oatcake, oatmeal porridge and sea foods.

Since a fundamental part of this study involves an examination of the accumulated wisdom of the primitive racial stocks, it is important that we look further into the matter of the smoked thatch. I was advised by the old residents that a serious conflict existed between them and the health officials who came from outside to their island. The latter blamed the smoke for the sudden development of tuberculosis in acute form, and they insisted that the old procedure be entirely discontinued. For this purpose the government gave very substantial assistance in the building of new and modern homes. The experienced natives contended that the oat crop would not mature in that severe climate without being fertilized with the smoked thatch. While they were willing to move into the new house, they were not willing to give up the smoking of the oat straw used for the thatch to prepare it for fertilizing the ground. I brought some of this smoked thatch with me both for chemical analysis and for testing for the influence on plant growth. This was done by adding different quantities of the smoked thatch to a series of pots in which oat seeds were planted. In Fig. 8 will be seen the result. The pot to the right shows the result of planting the oats in a sandy soil almost like that of the Islands of the Outer Hebrides. The oats only grew to the fuzzy limited condition shown. As increasing amounts of this thatch were added to the soil, there was an increase in the ruggedness of the plants so that in the last pot to the left tall stalks were developed heavily loaded with grain which ripened by the time the growth shown in the other pots had occurred. The chemical analysis of the thatch showed that it contained a quantity of fixed nitrogen and other chemicals resulting from the peat smoke circulating through the thatch. This explains the confidence of the hardy old natives who insisted on being permitted to continue the smoking of the thatch even though they did not live in the house.

A dietary program competent to build stalwart men and women and rugged boys and girls is provided the residents of these barren Islands, with their wind and storm-swept coasts, by a diet of oats used as oatcake and oatmeal porridge; together with fish products, including some fish organs and eggs. A seriously degenerated stock followed the displacement of this diet with a typical modern diet consisting of white bread, sugar, jams, syrup, chocolate, coffee, some fish without livers, canned vegetables, and eggs.

Next

Table of Contents

Back to the Small Farms Library