10. Pain and Travail in Nature

WE are now going to observe the conjugal behaviour of the king and queen in more detail, and will see three phenomena which are very wonderful. The word wonderful does not fit into science, for from one point of view every natural occurrence is as wonderful as another. But we are justified in using the term when we meet a phenomenon which is such an exception to the ordinary rules of nature that it appears to be miracle. The early behaviour of the king and queen is a phenomenon of this kind. It reminds one of the fairy-godmother who waved her wand and turned the pumpkin into a coach and the mice into prancing steeds. The hidden meaning of what I am about to describe has escaped experienced observers. The naturalist Grassi studied these things in very favourable circumstances, but he did not fathom their meaning.

Much depends on the particular aspect in which the observer is interested. If one is interested in behaviourism, and has some knowledge of it, one sees much the entomologist overlooks. His powers of observation are trained to notice form; he is interested in naming and classifying; to him the dead insect is often of more worth than the living one. This does not mean that his work is of less importance; it may be greater value than pure psychological investigation; and is far more difficult because less interesting. If, however, these things escape the experienced entomologist, it becomes necessary for us to take particular care lest we miss them too.

Up to the moment when the first garden has been made and planted and the first eggs are laid, the two insects, the king and queen, ordinary four-winged neuropterous insects, have been busy building their home, laying eggs like thousands of other insects around them. They have laid aside their wings, it is true, but they continue to behave like true winged insects. Then, however, strange things begin happening, so strange that we can hardly believe they actually occur.

While the queen is laying her eggs our searchlight disturbs her less than at any other time. It seems clear that her important work occupies her attention so deeply that even a cataclysm as the sudden flashing of an electric torch does not frighten her. She makes curious preparations. For a long while she stands on the place where the eggs are to be deposited, before she begins laying. Her body is in constant movement. The antennae sweep in circles and her jaws move ceaselessly. Occasionally she lifts the hinder part of her body in just the same way as she did when she was sending her first signal to her mate. Two or three times before the eggs actually are laid, she turns round and looks at the ground as if she expects to find something there. With the actual laying of the eggs the bodily contractions increase tremendously. When the first batch is laid, she turns round once more and examines them long and carefully. She touches them gently with her jaws and front legs, and then she lies motionless beside them for a time. What does it all mean? We are here observing one of those wonders which I promised, and which is found in no other winged insect, nor in any other insect of similar development. Unless one has witnessed a similar occurrence in an animal a little higher in the scale of life, one cannot realize the significance of this behaviour. Actually we have witnessed the first appearance of a complex which plays a mighty role in the decadent and unnatural condition of the human race today. We are seeing the first evidence in nature of birth pangs. We think this cannot be the case in a winged insect. Surely it must be impossible. How can one tell that the queen's behaviour is due to pain.

One knows what usually happens in insects. The female builds a home, fills it with food, lays her eggs as easily and carelessly as if she were eating, drinking or cleaning her antennae. The male never appears on the scene. After the honeymoon his part of the work is done. The female's work also concludes with the building of the house and the laying of the eggs. She never sees her babies. She would not recognize them if she did, for how could she, a beautiful flying creature, have given birth to these odd little grubs, or wriggling worms?

Another thing. One has never seen a real insect baby. One expects it to be a caterpillar, then a cocoon, from which eventually comes the imago, the perfect insect, which does not differ from the parent. But a little white insect baby is found in the termite which does not undergo any further metamorphosis; which is born weak and helpless, and grows stronger slowly, just like a human baby. Does one see such anywhere else in the insect world?

There are instances of this, but never in an insect at the same stage of development as the termite queen. Let us turn to the study of the behaviour of another creature, which is zoologically classified near the insects, but which psychologically should be in the mammal class. I am referring to the South African scorpion.

Among my tame scorpions there was a gigantic female which gained a good deal of fame. She was five and a half inches long. She first introduced herself to Mr Charlie Pienaar, by killing a full-fledged chicken in his presence. She tackled the chicken's leg, clung on, and gave one sting of her deadly lance, just above the joint. Within a few seconds the chicken was paralysed and was dead in ten minutes. Later on she became so tame and knew me so well that I could push a finger before her suddenly and allow her to grip me with her claws. She would bring her sting into contact with my skin, before recognizing me. Immediately she would relax and withdraw her dangerous weapon. I could handle her freely. She liked being scratched gently. Shortly after she came into my possession I noticed that an interesting event was shortly to take place. I watched her continually and gave her every care, for I wished to observe every stage of the process. I must admit that in those days I knew so little zoology that I expected to see her lay eggs. I was astounded therefore to see her give birth to sixteen living babies. Fully harnessed and spurred they made their entry by pairs, small white helpless babies -- but perfect little scorpions. There was no doubt at all that the delivery caused the mother much pain. I remember a woman asking me anxiously whether the young ones were born with pincers and stings, and then giving a prayer of thanks that human babies at least do not possess these.

What seemed very strange, too, was that the scorpion mother loved her queer little youngsters. Very carefully she helped them on to her back, where they remained sitting in two rows with their heads and pincers directed outwards and their tails interlaced behind them. I knew her well enough to tell by her behaviour that she would not allow any handling of her babies, so I did not risk doing this until they were fully grown. The mother would tear their food into small pieces and feed them carefully, while above them she waved her sting defensively. A more loving mother you will find nowhere else in nature.

It immediately seemed that one was dealing here with one of nature's deepest mysteries, and that we were nearing the boundaries of yet unexplored country. Of the appearance of pain in nature, no satisfactory explanation has yet been given. Many theories have been formulated, some of them probably bordering on the truth, but I know of no naturalist who has given a well-grounded and true analysis of the subject. Those who have, by original research, even approached the secret of birth pain, can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

One realizes that birth pain is a great mystery. One knows that pain in general is a warning signal to living creatures. If pain were to disappear from this earth, life would soon cease. Without pain organic matter cannot exist. Everywhere in nature pain acts as a defence -- except in the case of birth. Why then do we find this agony of suffering at the birth of highly developed animals? It plays such an important part and is so common that it must have some equally important purpose. What purpose had natural selection when she allowed this amazing exception to the general rule? Birth pain is clearly not protective; indeed, it is the very opposite. One can often learn the meaning of normal phenomena best by observing what happens in unnatural and abnormal manifestations of the same thing. One knows that in apes, in tame animals and in humans, the mechanism which causes birth pains may be a danger to the lives of both mother and child. Yet birth is the great end of the struggle for existence, the event which nature, as it were, considers the first and most important, which would protect with all her powers and make safe for mother and child. Why should it be coupled with violent and non-protective suffering, which increases as you mount the scale of life? What does this mean? We will follow the path of pain as it winds the way through the dark ages.

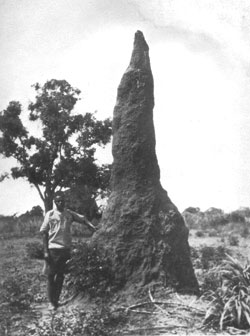

A tower termitary

|

With an ordinary immersion lens dipped in a drop of stagnant water from a cattle kraal, for one can see life with an immersion lens without stain or oil, I watched the movements of Volvox and Amoeba for hours on end. Many unnatural conditions in their environment may be brought about. A red-hot needle pressed against the glass will cause a sudden rise in temperature of water film, enough to cause the death of a unicellular organism. One can introduce strychnine, carbolic acid, or arsenic over the outer edge of the film. A strong ray of red light, sharper than a needle point played over the film will also kill the organisms. In these experiments one gains a certain insight. One sees the unicellular animals start and retract from the dangers you have caused. If you study similar instances in higher animals, you find that nature guards the way to death by pain.

On the unaffected side of your film you see the cells budding, dividing and multiplying.

Someone once said that all behaviourism in nature could be referred to hunger. This saying has been repeated thousands of times yet is false. Hunger itself is pain -- the most severe pain in its later stages that the body knows except thirst, which is even worse. Love may be regarded as a hunger, but it is not pain.

What protects animals, what enables them to continue living, what assures the propagation of the race? A certain attribute of organic matter. As soon as one finds life, one finds this attribute. It is inherent in life; like most natural phenomena it is polarized, there is a negative and a positive pole. The negative pole is pain, the positive pole is sex. This attribute may be called the saving attribute of life; and it is here where one comes closest to what appears like a common purpose beyond nature.

All animals, large and small, possess some mechanism for feeling pain, and this pain always acts as a safeguard against death. An animal struggles to get out of the water, not because he is afraid of death -- of which he knows nothing -- but because the first stages of drowning are extremely painful. Close to the pole of pain we find fear as another urge towards certain behaviour. The other pole, sex, is more complicated -- the final result of it is mother love.

In the apes, in a lesser degree, and in man, in the highest degree, there has been a great degeneration of both poles. In man there exists no longer any selective power against the attack of pathological organisms and thousands of organic diseases. The result is that the mechanism of pain, which developed only as a defence in nature, is brought into action uselessly as a result of the ills man is heir to, and from which animals in natural environments are free. Sex has become degenerate in man to the same degree. In nature, the sexual urge, like other race memories, needs an external stimulus before it is roused. As we have seen, this is scent alone in most mammals. Sometimes scent and colour go paired. In such cases we find brilliant colourings in the female as well as scent. In such animals destruction of the olfactory sense in the male means the end of sex.

In the ape and man we find the first animals, excluding tame animals, in which sex can be roused without an external stimulus. The reason for this is one that has been mentioned before. In man and the apes all perceptions, all experiences are registered as individual causal memories. The cortex of the brain is the organ of this function. The first awareness of sex must be transmitted through the cortex as an ordinary causal environmental memory where it is immediately absorbed as a separate memory. The ape and man remember this as a pleasurable experience to which they can react at will. The result is that the greatest of all natural laws, periodicity, is lost in the human race. The periodic organic condition, which should rouse the sexual sense, has become an absolutely useless, degenerate, pathological manifestation. The ultimate result, birth, which in all other animals is safe and certain, has become in the human a major surgical operation, where the lives of both mother and child are endangered. Without skilled help in labour the civilized races would vanish from the earth in three generations, said a famous German obstetrician. Two-thirds of all the organic and mental disease of man may be ascribed to the degeneracy of the sexual sense, said another expert.

A little way behind man we find apes, with similar degeneracy and similar results, only in a lesser grade. We have taken a brief and general glance at the two poles, pain and sex. There still remains the mysterious exception, birth pain. We realize at once that this has no connection with protective pain. It guards no road leading to death; no animal can escape from it. We have learnt the general rule that every instinctive action is unlocked by one and only one key. We have seen how in the termite the stimulus or key to sex is flight, and in the kudu scent; how the whole aquatic life of the otter is initiated by the sight and touch of water. In exactly the same way we find that birth pain is the key which unlocks the doors to mother love, in all animals from the termite queen to the whale. Where pain is negligible, mother love and care are feeble. Where pain is absent, there is absolutely no mother love. During a period of ten years' observation, I found no single exception to this rule. Some naturalist once suggested that the function of birth pain was to draw the attention of the mother to the young one. This is not so. There is no such thing as 'drawing attention' in the instinctive soul. The unlocking of the mother love complex through pain is beyond consciousness, beyond the knowledge of the mother and has nothing to do with drawing her attention to her offspring. Naturally it was not enough to show the connection between birth pain and mother love in order to prove that one was the result of the other. A large number of experiments dispelled all doubt. The following notes will explain the general principle.

For the experiment I used a herd of sixty half-wild buck, known in South Africa as Kaffir Buck. I have proof that during the previous fifteen years there had been no single instance of a mother refusing her young in normal circumstances.

- Six cases of birth during full anaesthesia of the mother induced by chloroform and ether; unconsciousness in no case lasted for more than twenty-five minutes after delivery. In all six cases the mother refused to accept the lamb of her own volition.

- Four cases of birth during paralysis -- consciousness and feeling were partly paralysed but not destroyed by the American arrow poison curare. In all four cases the mother appeared for over an hour in great doubt as to the acceptance of her lamb. After this period, three mothers accepted their lambs; one refused it.

----To prove that refusal on the part of these mothers was not to the general disturbance caused by the anaesthetics used, I did the following experiments:

- In six cases of birth the mother was put under chloroform anaesthesia immediately after delivery was complete but before she had seen her lamb. Unconsciousness lasted about half an hour. In all six cases the mother accepted her lamb without any doubt immediately after she became conscious. Similar experiments with curare gave the same result.

From these and other experiments I became convinced that without pain there can be no mother love in nature, and this pain must actually be experienced psychologically. It is not sufficient for the body to experience it physiologically.

Mother love is a psychological complex, therefore the key which makes it function must be a psychological one, analogous to the psychological impression of flight in the case of the termite.

We have seen what the result of birth pain was in the case of the scorpion mother. In a later chapter we will see the interesting way in which the same principle is verified in the termite queen.

This complex, as we find in all such complexes of the instinctive soul, has long ago ceased functioning in the human. Birth pain has become psychologically a useless rudimentary manifestation, which now is a source of danger, like most rudimentary organs.

One expert has written: 'When nature wishes to annihilate a race, the first attack made is in the direction of the sexual sense.' This is said in topsy-turvy fashion, and I am not sure whether it is true. But one fact is clear, the degeneration of the sexual sense is responsible for the greatest part of human suffering. Yet one part of sex, mother love, gave a twist to man's psychological development which was largely responsible for his domination of the earth.

Next: 11. Uninherited Instincts

Table of Contents

Back to the Small Farms Library