ONE hundred pigs will clear and manure one acre of land in one month. I make this statement with the confidence of experience, hoping that various people will try and prove me wrong, which will certainly result in their enthusiastic adoption of this idea of mine. You will probably be asking what size of pigs and what sort of land. I am not pretending ten sows and ninety newborn piglings will do it, but ten sows and ninety six-month stores will do considerably more. It is vitally important to get these figures well in your head so that you realize that you are not only keeping pigs – you are making land. You are going to turn land that is worthless into land that in two years will be as productive as any in the district and in four years will be the cleanest and most fertile. This idea can be developed to make farms out of the wilderness and reduced to solve the problem of the vicarage garden!

The rangy vicarage garden probably extends to a quarter of an acre; the vicar does the vegetables in his spare time and his wife the flowers. They are both busy people, farmyard manure is lacking and the weeds seep in year by year. The target should be one sow, her litters kept to pork stage. Begin with four three-months-old gilts. One hundred pigs, one acre, one month, and therefore four pigs, one-twentieth of an acre, a plot ten yards by twenty, make it a trifle smaller, and it will take one roll of wire netting. The house the vicar will make in a morning, and on the following Sunday I should be surprised if his sermon were not on building houses. His electric fences will cost him £15 and there will be straw. The standard price of straw may be taken at 2s. per bale; if it is delivered expect to pay slightly more. Always have a bale in hand for emergencies – cloudbursts for instance – and expect to use half a bale weekly. It is probable that three-months-old pigs which are less than half-grown would need more than a month to make their pen a garden, but when they had finished they would leave it in a condition to grow a green crop with plants put straight in on the undug ground. I have done this with brussels sprouts. If peas are chosen, then lime before you dig, and you will get the best peas that have ever been grown in the garden. Two further points: I advise our vicar to start with four pigs so that they make a handy unit for warmth and company, are less likely to be forgotten, little more trouble to tend and do a worthwhile job. Two young pigs, as everyone knows, is the irreducible minimum. Secondly, our vicar must expect to feel uncomfortable when he reads the passage about the Gadarene swine and may evince an unusual warmth towards the claims of the Higher Criticism.

Remember, concentrate your pigs, let them clear the land, then crop if you would enjoy your work. Concentration also gives you a tremendous saving in time. I am talking now of the time when you are well into the collar and have in-pig sows, sows and young and stores to plan for. If you have your pigs dotted about in paddocks of an acre or more, so that they will not disturb each other and save yourself time in housing and fencing erections and re-erection, you will find yourself spending needless hours toiling from field to field fetching a tool that has been left somewhere else, or feeding or carrying bedding or water. Walking exercise over rough ground I have always rated very low as a pastime or occupation. Apart from this a bunch of pigs in a normal three- or four-acre field have too much room to be effective. Within a week the ground around the house has been well dunged, within a month it has been overdunged. It is reasonable to feed pigs – at any rate sows and strong stores – a hundred yards from their house, but two or three hundred yards is too far; in addition, some of the pigs may miss the dinner bell and go hungry.

I think it is now time to visit the ironmonger and invest in tools. First a spade: see it is a really good one – no army surplus spade shovel. Secondly, a billhook which must also be heavy and good. By the by, when I say ironmonger, I mean ironmonger and not a shop stocking house requisites plus a few tools. Use your common sense, every market town has at least one good ironmonger, and if he displays tools and agricultural requisites he is probably the man. A good billhook must be heavy as you will be cutting down tough saplings, and a heavy hook does half the work for you. A pair of handy pliers that will travel comfortably in your hip pocket is useful and, finally, a staff hook for cutting down brambles. There is one other tool you can ask for, but do not expect to get. I refer to a shepherd's crow-bar. These are roughly three feet long, pointed at one end and they are heavy. Ironmongers seldom have the right length or the right weight; a country blacksmith would probably fit you up. Your iron bar has to make all the stake holes for your fencing and tap the stakes to firm them, so it is very important. Pitching an iron bar, making holes with it, dropping it each time into the same hole instead of scoring on average one bull, three inners and one magpie; pitching an iron bar is an art – practise it on the quiet.

Do not on any account invest in a sledge hammer or 'biddle' as we call them around here. It is just another heavy tool to be carried around and mislaid, and on a critical occasion either the head will fly off or the stem will break. Biddies and sledge hammers are the mark of the greenhorn – avoid them! Finally, before you leave your ironmonger buy a pot of white enamel and a paint brush and, when you reach home, paint half of each tool white, a white band a foot long on the iron bar. Of course, I know you will never leave a tool on the ground and forget where you have put it, but a friend or employee might, and a white band hits you in the eye. Besides, if someone borrows your tools, there is no doubt as to which is yours. I nearly forgot our friend the crosscut saw. I like the sort with a second handle that can be fitted up so that two can use it if necessary. Of these tools the spade and the iron bar are, or should be, kept on the job and the others in the toolshed. It will save you many hours if you always leave spade and bar at the corner of a pen or – if you work in paddocks – at the gate, if you like. There should be a corn-bin holding two or three hundredweight at each feeding point and a bucket. As far as bins are concerned, I find the circular ones with a pointed top are most satisfactory. If money is short an old oil drum with the top removed and a short sheet of corrugated-iron covering the top will do, but it is not entirely weatherproof.In fencing pigs, remember it is a trial of wits between you and the pig. You are going to induce him, not to force him, to stay put. A straying pig is not an erring pig; probably it is just a hungry pig. What is normally called pig-fencing wire is only pig-proof when strained tightly with a strand of barbed wire along the bottom and two-inch posts five feet apart. Pig-fencing wire is heavy and expensive. I don't like it because it is expensive. I won't have it because it is heavy. You will agree with me when you have carried a fifty-yard roll over a muddy ploughed field. To induce pigs to stay put in partially confined quarters (pigs will obviously stay in a four-acre field far more easily than in a quarter-acre paddock), the prime requisite is an electric fence that works. It's not my job to recommend, but I should start with one like your neighbour has and finds satisfactory. Electric fencing wire for pigs can be light, as light as they make it, you are going to use no wire strainers and if it breaks it is easy to join up again. You can, if you like, buy special metal standards for pig fencing, but I should not recommend them. With a wire one foot from the ground it is difficult enough to avoid short circuits using wooden standards, and I should imagine that metal standards have caused a good many people to give up electric fencing. We use short stakes cut out of hedges and get insulation with a strip of rubber: a length of cycle inner tube is admirable. In pouring rain, of course, the current shorts, but in pouring rain the pigs are inside and not fence-breaking; and, taking it by and large, I find my batteries last pretty well, which means that short-circuiting is not serious. The stakes should be eight to ten yards apart, and be sure that your comer stakes are exceptionally strong and exceptionally well put in. The wire should be eight to twelve inches from the ground, according to the size of the pigs that you are fencing, and be sure to keep your right height in hollows and hummocks. One point about taking this wire up again when you move camp. Do it carefully. All wire should be rolled up on wiring reels, and be sure they are big – about the size of a cycle wheel, as rolling wire on small reels means extra work and extra bending for the wire, which is weakening. We use old fifty-gallon oil drums. The proprietary reels that collapse and enable one to remove the roll of wire, I find, are a snare and delusion, as the wire is always very difficult to unroll again if it has many joins, and I confess my wire is full of joins.

Many fencer salesmen are quite sure that one or two wires, put up six inches apart, are pig-proof. One electric wire will undoubtedly keep sows in a five-acre field, but when one has a hundred pigs in four pens on an acre of ground it is obvious that more drastic methods are necessary. I find that two-inch-mesh wire netting, two feet high, one foot behind the electric fence, prevents fence-crashing at feeding time; particularly if the real height of the wire netting is two-feet-six or three feet, so that the bottom can come forward towards the worst fence-breaking pen and be secured on the ground by spits of earth thrown on with a spade, thus preventing the pigs from readily getting their noses under it. This, of course, means an extra electric wire, as it is necessary to have one on both sides of the wire netting, but it is in my experience the only way to keep pigs secure in small pens. And if one is going to carry pigs to pork-weight in the open the less incentive they have to wander the better. I have always found it best to have a separate fencer for each pen of pigs.

Let us imagine that you are about to embark upon your pig venture as I did with fifteen three-months-old gilts and a young boar. The first thing to do wherever you are, and on this occasion I am putting you on a bit of derelict woodland, is to make your ring fence secure. Believe me, it will save you much worry and hot words – not that your pigs will do any harm: they won't. I had mine out two or three times on growing sugar beet just beginning to cover drill. They never touched a leaf, but my neighbours fretted themselves sick. Off you go, then, and clear a two-foot passage inside the hedge, with your staff hook for the brambles and your billhook for the bushes, and as you go cut out stakes for your wire netting and electric fencing, for, of course, you haven't been such a fool as to haul coals to Newcastle!

v. Marginal land. A bundle of laurels for house makingI expect you will agree I am right and will make the first pen for your fifteen gilts about a quarter of an acre in extent. You will begin to appreciate my wisdom when you have got about twenty yards down your hedge and are reflecting that it stretches for at least a hundred and fifty yards. I do not blame you if you break off immediately to locate a transverse path or clearing which will save your having to hack and swear your way through brambles and nettles across your front as well as down the hedge. Returning to your hedge, you will be quite surprised to find how quickly you finish your job. The front is easy: a nice two-foot wire-netting fence well buried at the bottom, with an eight-inch electric wire in front. What about the other side? With luck there is a good deep stream on that side and pigs can't swim: if they do they cut their throats – everyone told me that at school.

vi. Marginal land. The demolition squad

vii. Marginal land. Woodland houseOh, my friend, my friend, I weep for you and laugh too, as I remember a certain summer evening when I found a couple of sows and a boar wallowing in just such a stream and having, as it appeared from the scored banks, some difficulty in getting out. It was hot weather and I was not wearing a shirt, so I kicked off my shorts with my boots and hoped no one was looking. By dint of muddy and vociferous work on my part, and low grunts that might have been chuckles on theirs (perhaps I was tickling them under the arms), I at last got them safely on dry land. I was about to clean off the mud when I spied two weaners swimming buoyantly across stream to investigate my neighbour's pasture. To see was to act, and again praying that I was unobserved, I clambered up the bank in pursuit. The little pigs enjoyed the joke particularly since my neighbour had cut his thistles. I gave up after five minutes, feeling that the Indian fire walkers had nothing on me and determined never again to leave a boundary stream unfenced.

Yes, you will have to be very careful with that stream. Leave them a stretch, perhaps ten yards, where you can fence it well the other side. Fence it well above and below with hurdles or some extra good and well-staked wire netting, so that the pigs can use this strip as their wallowing and drinking pool. It will make them happy and relieve you of hauling water. Having water for the pigs without hauling will amply repay all the 'Devil's Island' experience of the clearing, but your real reward will come some very hot day when everyone else's pigs are lying and panting and yours are dozing happily under trees, covered with clean mud.

Of course, if you have not got a stream you will have to haul water, and the plan is then to house at the far end of the pen and to feed and water as near road-head as possible. If you have a stream, use it if you possibly can. You can't use it unless the pigs can lie on dry beds whatever the weather; that is to say, the ground must not be all waterlogged. Neither must it be entirely tree-covered, but if water is there for the taking, three-quarters of your hauling problem is solved.

Once you have your ring fence secure and your pigs at home, turn to and get your next pen ready. To begin with, the first one will probably be cleared before you anticipate, and, secondly, fencing that has had time to settle is much more secure than when newly erected. You will also have to decide how many pens you will need. From the point of view of labour, and simplicity, the fewer the pens the better. It is not possible to run them as one big happy family. The boar will not hurt the babies, and expectant mothers are always given housing priority. However, there is always the danger of strong pigs robbing the weaker and it is very difficult to ensure that no pig is being bullied and kept from the trough. Undoubtedly the best plan is to keep the in-pig sows in one pen and the rest in monthly batches.

If things are going well now, the gilts are thriving, the clearing is progressing and has progressed better than expected (it is remarkable, for instance, what can be done in the summer holidays if one has some healthy open-air fans among one's friends), it would be a good move to venture to market and buy a batch (twenty to be safe, never more than thirty) of new weaned pigs to fatten out for pork or bacon. Monthly visits to market keep one from undue optimism or depression as to the value of one's own pigs. I usually find I have underestimated the value of mine.

Nowadays the lorry has wiped out the market town and all the marketing of a county is done at two or three centres. Do not be rushed by the term market tacked on to the local town – take a look at the provincial press, find where the stuff is going, and see a hundred batches of pigs sold, not just three or four.

You may be fearful of swine fever, you are wise if you are, but there is no more reason that you should buy swine fever from market than that you should catch 'flu at the cinema or the pub. Be careful, of course; on no account buy pigs in one pen of various sizes and possibly colours: two saddle-backs and six blues, for example. The glib vendor may tell you they were born like that: listen to him politely, but do not buy the pigs. They are almost certainly two litters put together, and two small litters probably means a high mortality on the sow. Only buy pigs that are 'warranted right': this means that you can claim from the vendor if anything goes wrong with them in the course of a week; and, if it does, the louder the noise you make the better. Personally, I should advise you to buy pigs that are comfortably bedded down, clean in the coat but small. They probably come from a man who understands pigs but is inclined to underfeed and does not worry about creep feeding. They will do well under your management.

I think it is a good thing not to feed pigs when they get home from market. They have been very likely overfed for the previous twenty-four hours, and they will be ready to start the new regime next morning. Always feed the newly bought pigs last. If they are dull in the coat, with perhaps a certain cough, you will be wise to worm them, although I have never been able to get very satisfactory results. Read the instructions on the worm powders carefully and obey them – you are dealing with something that may be dangerous. Look out for the first few days for any pig that lies in the straw – when the others are feeding – or stands and pants. If a pig feeds shy at two meals ring up the auctioneer and report it. You will get no satisfaction after the week is up. If the first lot of stores are thriving and you still have room and money and time, you might buy a second lot a fortnight later. It is all good experience and a quick turnover, but be sure you have the right accommodation ready for your pigs. No makeshift accommodation for your pigs because they are cheap!

So far I have dealt exclusively with the comfort of the pigs. What about you? First of all, mobility. Be lazy; walk as little as possible: a cycle is an excellent servant, but it punctures and is impeded by mud. I think the best investment for a pig pioneer is a Land Rover or a jeep. They can pull a caravan or trailer, haul what you want and go places in the evening. I am not anticipating that you will want to go places much, but to feel you can go if you want to gives peace of mind.

Never send a coat to the jumble saleAs for clothing, you will need Wellingtons – two pairs in winter – but don't wear them always, only in wet weather. They very easily tear on sticks and roots. I think the best footgear are well-dubbined hobnail boots. Personally, I wear them without socks, and now feel I am as tough as the average woman. It saves an enormous amount of sock-mending, one's feet don't get cold when they are working, and an adhesive dressing soon heals any sore spot. I use Willesden canvas leggings to keep my trousers clean, and in wet weather oilskin leggings to keep my knees dry. Somehow if one's knees are wet one is wet all over. I never part with a raincoat and the worse the weather the more I pile on. The best goes inside, the rest you select according to whether you want warmth, dryness or merely protection from mud. I was once ridiculed for describing the ideal pig pioneer as one who was weatherproof, had horse sense, and was chore-minded. I still cannot think of a better definition.

I BELIEVE sensible adequate housing is the most important factor in pig farming. The pig increases in size so quickly that a house that will hold twenty pigs in October will only shelter fifteen of them in November, and ten in December. Failure to realize this will lead to pigs overcrowding on a dirty night; chills and coughs. By sensible I mean reasonable ventilation and no bottle-necks. Houses that are in depth rather than width tend to encourage pigs to crowd at the back. A triangular-shaped house may result in small pigs being wedged in the base angles and suffocated. Facing one's house in the right direction is almost as important as the design of the house. Which quarter is your rainy quarter? If it's in the south-west, then face your houses north or east. If you have not realized this already, remember it from now on. It took me twenty years to discover. I may be dumb, but I have completely cleared myself of chills and coughs at last. Pigs can stand a cold wind especially if they have plenty of bedding, but rain one cannot keep out of a house if it is facing towards the rain. The result is that the pigs huddle to the very back of the house, and death and disease follow.

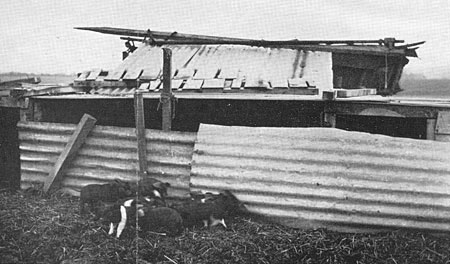

Housing must be mobileThe tendency of the pig to grow out of his housing is worth more than a moment of reflection. How long will it take you to get a new house from your merchant delivered and erected for use? A week is a fair estimate and regardless of the cost, which will be roughly three times that of a home-made house. Serious damage can be done by overcrowding pigs for a week. I lay it down, therefore, as axiomatic that houses should be home made.

The roof is simple. The prime requisite is that it must be weatherproof. The second, for our mobile methods, that it must be reasonably light and easily handled. The answer is corrugated iron in some form. Nissen-hut sections will do. Always buy the longest span within reason and a strong gauge of ordinary corrugated iron to avoid sagging. I can recommend no other roofing. Felt-covered boarding, for example, is heavy and easily breaks, and tarpaulins are quite unreliable in a wind. If you or your neighbour grow a lot of corn, straw bales are available and cheap for the sides of your houses. I disapprove of covering the bales over with wire netting to prevent the pigs undermining the walls. Pigs will only do this if they are short of bedding, so that if they try it, it is a hint to you. Besides, when the house is moved it is doubtful whether the wire netting will be any good again, so that in the end your bale house, with bales valued at two shillings each, will be rather expensive. However, if you are determined on bales I do not blame you. It is as simple as making pigsties with bricks on the nursery floor. Well, perhaps not quite that, as some of us have experienced. The bales must be kept in place by stakes three foot six inches long, driven into the ground. Then there is the matter of roof fall. If one side is made three bales high and the other two bales high, the fall is too steep and the problem of blocking the end presents difficulties. If it is blocked, two bales are entirely given over to the weather, as it is impossible to roof them. If it is not blocked, there is a howling gale coming through that right-angle triangle two feet high and eight feet long. One last point against bale houses. The roof must cover the bales if they are to last, which means four feet of your corrugated roof space is devoted to keeping your walls dry.

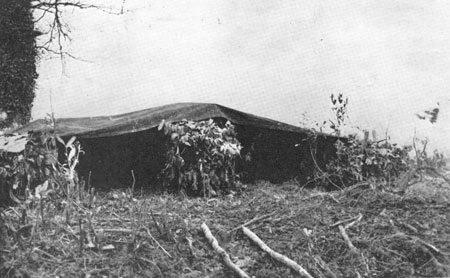

Quite the cheapest and warmest house that can be made, especially if one is hedging or if one is working woodland, is the brushwood house. The house is, of course, roofed with corrugated iron, but the sides and back are built of faggots roughly eight feet long, tied in two places securely. Personally, I use old bale twine which all farmers are glad to get rid of. The length of twine as it slips off the bale is just the right length to tie a faggot. That is to say, the faggot will be a handy size to build with. A peculiarity about these faggots is that they must be approximately the same thickness at either end, so when one is making them they should be laid alternately head to tail. It is, of course, a reasonable proposition to use wire for tying the faggots, in particular condemned telephone wire has been strongly recommended to me. It will certainly last virtually for ever, and for that reason I would prefer bale twine and so lessen the risk of cattle deaths from wire swallowing, which were very prevalent when wire was used for hay-baling.

My own experience is that laurels make the best brushwood houses. The leaves make them windproof and dry and prevent decay. Can anyone tell me why pigs will eat and enjoy the top inch of a laurel leaf but will go no further? If other wood is used so that the leaves wither and die, it will be wise to line it with sisalcraft paper. If on first introduction to their new house there is plenty of straw the pigs will leave the sisalcraft alone, although, of course, a sow about to farrow is a law unto herself. The right height for a pig house is three feet six inches, i.e. three feet and more on one side and three feet on the other, to get a good water shoot. Drive four stakes in eighteen inches apart and roughly three feet into the ground, and then ram your faggots between them, leaning the stakes together at the top to give increased rigidity. The back which puzzled us with our bale house can be closed with a triangular-shaped faggot. Remember the high side should be the weather side, so that the wind behind the rain drives the water off the roof by corning to the high end first instead of driving the rain into the roof by blowing from the low one. These remarks may have to be qualified by the fall of the ground. Obviously one wants the roof to shoot on to the lowest side to prevent the water seeping back into the house. The roof may be kept in place with other faggots or logs; weight it down and, if necessary, tie the weights in place, don't just tie the roof down. The theme song for all this house building may be found in Matt, vii, 24. ['Therefore whosoever heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man, which built his house upon a rock.'] One last point: don't try to economize by building your houses in pairs. It is difficult to prevent one house being waterlogged and pigs dislike semi-detached residences. If in the course of months the faggots settle, all one does is to remove the roof and add a faggot either side to bring it to its former height.

A motto which pioneer pig men might well take to heart is: 'Haul no junk.' Avoid sales and, as far as possible, only buy what you can neither make nor grow. The faggot house is an excellent example of this motto. I bid you find an apt illustration of a suitable pig hut for open-air work, which if 1 mistake not will be priced at between twenty and thirty pounds. Close your eyes and imagine that a lorry has brought it to the road-head and you have to get it into a piece of derelict woodland, perhaps over a steep slope across a watercourse, and between stumps and dead trunks, and ask yourself how much would be knocked off your house's value, not to mention yourself, before you had it in situ. The folly of buying houses is obvious but there are other lines. For example, square-cut, pointed stakes at about a shilling each – not to mention the haulage and carriage to the spot – often tempt the unwary. Clearing brushwood is an arduous enterprise, but if every straight branch of one to two inches in diameter and two feet six to three feet six in length can be used to save you money, instead of burned, how much stronger is your position.

In rough woodland your straighter poles will probably be birch; everyone says they rot quickly, and they do, but they will last as long as you need. Drive them in the other way up to the way they grow, for this stops the water being sucked up the sap channels and makes them last rather longer.

However, haul no junk and faggots from woodland. They are junk on cleared ground, so I do not recommend faggot houses here. Instead, I advocate home-made sectional houses. The height as before, three feet to three feet six inches, the lower the house the warmer, and there is no cleaning out to be done. A house seven feet by five will house one sow to farrow, two sows and their litters from ten days old, and the litters only up to three months old. The wood will cost you about four pounds and the corrugated-iron roof a couple more. Have an opening at the front, but no door. It is a good plan to have a few spare sides, then on a very cold night when the wind is in the north or east, these can be erected across the door at an angle to act as a windbreak. On no account nail up bags in front of the door for this purpose. They are a snare and a delusion. Try it in your own bedroom. The sections of the house may be bolted together, the whole house left rigid and carried from field to field on a buckrake. This is very satisfactory provided the tractor and buckrake are at your call for a whistle! Otherwise I like the house to be erected section by section, a stake driven in at each corner on the inside and the corners kept together and rigid to the stake with wire run through holes in the section, one about a foot from the bottom, the other six inches from the top.

The roof is, as usual, corrugated-iron sheets; the fall should be to one side, which means a difference in height of the two sides of about nine inches. In putting on the roof sheets always remember that the sheet at the front of the house should go on first. The wind blowing from the back of the house is then blowing over instead of into the laps. I used to recommend that these houses be put up in pairs so that corrugated sheets joining the two houses would make a third shelter, but in-pig sows are the only pigs I know that will sleep in the centre shelter; small pigs use it as an indoor convenience.

Skeleton shelter on wheelsHouses such as these have seen me through four winters practically without casualties except, of course, new-born pigs. I have had a sow farrow in twenty degrees of frost and found her with ten grand pigs at teat in the morning. This leads me to believe that if properly sited, using natural shelter where available, I am safe in recommending them in any part of the British Isles. So much for warmth. I wish I could tell you how to make these same houses cool and airy in the summer. In my opinion it is far harder to keep pigs cool in summer than warm in winter. On a cold winter night the pigs bunch up for warmth. In the hot summer they want to thin out, no pig touching any other hot body, and where are they to spread to? I can only advise you to keep your roofs covered with straw – the straw the pigs nose out for doormats will do – and in hot weather sprinkle your roofs with water. Summer is the time for odd houses. The best I have is an old elevator, the floor corrugated as it is covered with straw, and on the south side a length of strong pig wire with canvas laced on it. This gives a tent-like shade and in very hot weather the bottom can be raised on an old oil drum to give a through draught. I hope to make a similar shelter from an old hay loader. Old wagons provide cool shade. It all sounds very odd and very untidy. It is both, but if it means that the pigs don't pant I am content. Much can be done by using shady hedges to the full; it may mean altering the fencing along one side to include a hedge. Try and have a drum of water handy to each group of three houses or so, and in the middle of a hot day chuck a bucket of water over the pigs as they lie. Filling drinking troughs in the heat is a mistake, but sluicing the shelters is well repaid. Finally, and this is absolutely the end, the wise pig-man who will note his pigs' requirements in hot weather will quite frequently visit his pigs at night and will not wait until the bad weather. There is no question that pigs love fresh air per se. I have found strong pigs sleeping in the open in February, in nests of five or six with houses half-empty and full of straw. This chapter is full of meat, but I think there is little exaggeration. The pig will tell you – watch him!

I AM giving you a special chapter on the sow. If she does her job well most of your troubles are over. If you prove a good lieutenant to her, quick to understand her requirements and treating her with the respect she deserves, she will do her job properly. Let no man set himself as wiser than the sow, unless he be one of a family of eight born on the same day, all raised to useful maturity! There are two ways to buy a sow. You may buy a sow and litter at market: then you may be reasonably sure she is prolific and a good mother. There are snags, of course. Make sure that all the pigs are her pigs. Usually the family likeness exists and I should never risk a litter with half saddle-back and half white pigs. If there are a reasonable number of gilts in the litter this may be the best way of founding your herd, but if sows and litters are selling well it may be expensive. The other way is to buy a bunch of weaners and keep the gilts. In my opinion all gilts have the capacity to be good mothers. If they fail it is usually bad management. The practical blokes will always aver that the smallest gilt in the litter makes the best mother. The science behind the experience is that in each gilt the growth factor and the mothering factor are combined, and if the growth factor is in short measure, Nature has probably made it up in the motherhood factor. In addition, she will probably all her life be active and a good forager.

I myself prefer the second method for a beginner, as when they farrow in seven or eight months' time you will know your pigs and they will know you – as it were, personally – a very important factor. As soon as you have bought your gilts, begin thinking about a boar. While it is very nice to be the only man in the regiment in step, it may be an expensive hobby, so that I can only advise you to remember that if you choose a black breed you must expect to get £2 per head less for your stores. Buy your boar on the teat and choose a long boar from a large level family. If you cannot buy in this way, go to someone who will sell so. I would rather buy a crossbred blue pig in this way than a pig in a poke from a pedigree herd. When you have bought your boar turn him out with the gilts. He should be a month younger than them and – provided there is sufficient trough room and you see fair play for the first day or two – nothing but good will come of the early mating. The normal thing will be for most of the gilts to farrow at from ten to twelve months, the litter will be small, an average of six may be considered good, but the mother will learn her job with a small family, and by the time she is eighteen months old she will have caught up in size with the late farrowing. The advantage of having a boar a month younger than the gilts is that probably the date of conception is delayed one month.

Let us return to you with your batch of gilts and young boar. Feed them three pounds of nuts or meal, provided they have foraging, otherwise it will have to be more. Twelve-weeks-old gilts should certainly eat this amount; the pig does the bulk of his growing between eight and sixteen weeks and it is well-nigh impossible to overfeed him. Possibly a month before farrowing, if grazing is ample, you may be able to reduce By half a pound, but it should be done reluctantly, and only if they are getting lazy about grazing and their food. I always love to see a batch come galloping and barking up at the first rattle of the bucket. As farrowing time approaches, which is shown by the sow dropping in the belly and making an udder, watch the dung closely. If the grass is fresh and green there should be no cause for worry, but dung should be of a healthy human texture, if it is hard and dry something must be done at once. If you can, buy roots and cut concentrates by half, and give all the roots that the pigs will clear. If roots are hard to get, cider apples, by the by, are as good as roots. Then use Epsom salts, a small tea-cupful in the drinking water. You will be wise to experiment with Epsom salts early, so that you will know how much to give if the gilts are constipated after farrowing. As the gilts have been growing you will have been making houses and it is a good plan to erect them in the paddock where they are running, so that they can inspect.them, rub against them and be at home in them.

Do not hurry your expectant mother away at the last minute into quarters by herself. You will be lucky if you succeed without the help of three men and perhaps a dog. You will be doubly lucky if she is not back with her friends next morning. When a gilt is going to farrow she will find a secluded house and farrow. If she is a senior girl she may drive her room-mates out and farrow where she is. You will know she is going to farrow when she starts to make up her bed. My advice to you is to go home and forget about her until next morning: I know there are many who will counsel removing the pigs as they are born, tying the navel and removing the eye teeth. These things just cannot be done in a hut in a wood. If the sow is not naturally a good mother, out her; but if her bowels and muscles are right, she can be trusted to make a good job alone and the presence of a nervous human hovering in the background will only upset her and make her restless. A sow likes to be out of earshot of other pigs when she farrows, as then she knows that any squeaking demands her attention. A litter of a few days old in close proximity is sometimes disastrous – feeding time approaches with the usual squeaking and the farrowing mother next door fears it is her mismanagement that causes the noise. Her restlessness upsets her babies that are born and possibly causes one or two others to be born dead. So see that your gilts can get seclusion if they wish.

The morning after a sow has farrowed get her out of her house. If necessary, block up the door and do not let her back until she has dunged and made water. It may take fifteen or twenty minutes of your valuable time, but the alternative is one or two dead pigs the following morning. The first dung is always very stiff and hard but it should improve with a laxative diet. This morning promenade should be a daily routine for three days. The first three days are crucial and with reasonable management all pigs alive at three days old should be reared to pork or bacon. I think it is probable that if a sow has an accident and loses half her litter on one occasion, then at the next farrowing you will have to be careful that she does not lose the same number again. It may be a kind of mastitis in those quarters. Bottle-rearing pigs is a sound proposition and if your sow begins to lose pigs for no reason I should advise you to remove 25 per cent of the strongest and bottle-rear them until the sow is feeding and dunging normally, then put them back and watch them for twenty-four hours: probably the sow will rear them without further trouble. I have heard of pig-men moaning over cannibalism. In my opinion a pig will only eat her own or any other live pig if she is shockingly starved, particularly of protein. It is the normal function of a good mother to clear up a dead pigling or two with the after-birth, and there is no need to get windy or run to your neighbour about it. If two or three sows farrow on the same night it is a good practice to even up the litters next morning, but be wary of putting three-days-old pigs on a freshly farrowed sow. I used to run an electric wire around a new farrowed sow to give her seclusion, and prevent other sows pinching her food. I have abandoned this as I think that anything that makes one think a newly farrowed sow is all right for the first three days is a snare and a delusion, after that she will fend for herself.

viii. Another roofing idea suitable for the summer

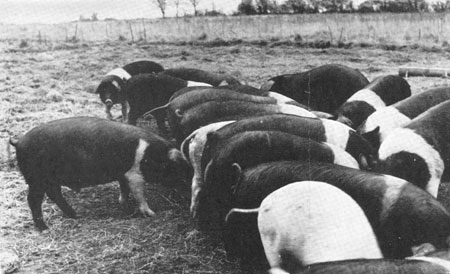

ix. Feeding Pigs – fattening as they grow

x. The sow. Winter or summer your pig should be as comfortable as this

xi. Management. A winter family, one day oldAt ten days to a fortnight, particularly in winter, it will be found that two sows and litters of approximately the same age will set up house together. This may be suitably encouraged by penning the sows and litters to one house. Feed meagrely until the sow begins to lose condition – four or five pounds is enough. The sow will be keen on her food and grazing. Something is wrong if after the first three days she spends her days with her piglings. Whilst mother is having her breakfast you can inspect the family, observe their dung and rustle them around with the hand to encourage activity. The weather, of course, must be respected, but by and large on the third day it is a good thing to turn them right out of the house and let them find their way home. At a week or ten days old a handful of nuts may be thrown in; when the sow returns and consumes them the little pigs will be interested. This leads the way to creep feeding at three weeks old. A creep may be made with two live wires and an electric fence all to itself, but I prefer one made with eight seven-feet gate hurdles, two feet six inches high, surrounded by an electric wire and with openings at the corners. It is completely sow-proof for one thing, and it also trains piglings to be confined. With a creep such as this it is simple to capture one or all, as required.

Now we come to castration. This needs careful planning as there are no four-feet walls to hold back angry mothers. The evening before the house entrance should be prepared so that the piglings may be secured by a sheet of corrugated iron across the front, kept in position by stakes. The stakes must be put in the night before so that the piglings can be secured in a twinkling. Also the night before, make a double-wired pen with a fence all of its own and a good battery about an eighth of an acre in extent and at least a hundred yards from the scene of operations. The next morning early, before the piglings are thinking about breakfast (remember they are less than a month old), the G.I. sheets are slipped in front of the houses and the sows drawn away to their pen with a thin dribble of nuts, the greater part of their breakfast being scattered in the pen. Do not on any account try to drive the sows to their pen: for your own sake the less they are upset the better. I have in the past been mauled by an angry sow and it is not pleasant. Being of a timorous disposition I like four men in the castration party. Number Four can then mind the sows. On the last occasion I was inside the house catching when 'prepare to repel raider' was called. There was a scrambling and rattling and a voice: 'We're all right, Dad, we are on the roof.' Poor old Dad had to catch pigs with his fingers crossed while an angry sow prowled around and the corrugated iron seemed really absurdly inadequate.

This is all a good story and perfectly true, and if it remains in your memory to remind you that castration is an important and difficult matter, it is well worth its place. However, with greater experience we now castrate at from four to eight days old. At this age the piglings are easily caught and make little noise. Feed your sow twenty yards from the house, run a tractor and trailer with a covered box on it up to the house, slip the boar pigs into the box and go two hundred yards away out of earshot. If there are two or more litters to be done the piglings should be colour marked to identify them. The piglings bleed less and swell less and, of course, struggle less. Castration is a very simple business and a good safety-razor blade is the best tool I know. Pay someone who knows the job to do the first few for you, but make up your mind that you will start at number six, for example, and once begun, do not let up.

Bedding: provided she has ample time to make her bed, it is impossible to give a sow too much bedding. What she does not require she will pitch out of her house. Leave her arrangements unmolested for two days, then in cold weather give her a little more, perhaps a third of a bale, every other day. The little pigs bury themselves in it and it makes a kind of blanket when the sow is away. I have known a sow farrow and rear her pigs with eighteen degrees of frost, in a half-inch wooden shed, corrugated-iron roof, but plenty of bedding. You may notice that whenever you put bedding into a house the sow immediately pushes some out. Don't be discouraged. She is putting out a doormat and garden path so that the piglings will not be belly-deep in mud when they venture out.

One last point – perhaps two. You may say that it is not worth my wasting my time, they are so obvious. Don't have month-old pigs and newly-born pigs in the same pen or so situated that the old pigs can get to the new mother. I have known the older pigs learn to suck the sow before she had farrowed and afterwards she let them suck with her own, to my loss. This sort of thing will happen when everything has turned out so simple that nothing is worth worrying about. Second point: when a sow starts to make up her bed never try to move her. Bring her bedding, erect a roof over her head as quickly as possible, if necessary. Do not so much as growl at her. If she is farrowing in a compound house with five or six dry sows in it, put up an extra 'lean-to' and bed it down well. The dry sows will be in it in the morning whilst mother is lying triumphantly with her family in the warmest part of the old house. Never wean before eight weeks, and in winter, when the weather is bad, it is a good plan to introduce the boar to the sows. He will not hurt the piglings, will produce extra warmth and by twelve weeks all the sows will have been served.

This chapter leaves you with a comfortable, benevolent feeling, does it not? I felt comfortable and benevolent when I wrote it. To finish up, I want you to imagine wet hell let loose. A ton of bedding has just been delivered: you have not had time to cover it, and it is saturated. Your houses, built three parts of the way down a steep hill, are being sluiced with water and veritable rivers. What do we do? Well, the bales are probably not soaked through. In any case wet straw is better than mud. Try and always have some spare houses at the very top, built where the bracken grows, and if you have in dry weather cut that bracken and tripodded it, you will thank God for that bracken which sheds the water better than straw. Then those pigs in the bottom houses – watch them, don't wait until it is dark. Take up the electric wire on the top side so they can climb to safety if they will, and encourage them to pass the fence boundary by a trough with some food in it. Fence-fearful pigs are much more worry than fence-breakers. Taken by and large, if pigs are accustomed to look after themselves they will come through an emergency pretty well, but if they are shut up they will die like sheep. An emergency is an emergency but mark you there should be only one the first year, possibly one the second, and none thereafter.

Next

Back to the Small Farms Library

Community development | Rural development

City farms | Organic gardening | Composting | Small farms | Biofuel | Solar box cookers

Trees, soil and water | Seeds of the world | Appropriate technology | Project vehicles

Home | What people are saying about us | About Handmade Projects

Projects | Internet | Schools projects | Sitemap | Site Search | Donations | Contact us