-- On the wrong side of South Africa's racial divide

by Keith Addison

South Africa, 1974

|

Stories by Keith Addison |

|

Zebra Crossing -- On the wrong side of South Africa's racial divide.  Kwela Jake Kwela JakeSold into slavery Mamelodi Finding Tom Hark Return of the Big Voice Brother Jake |

| Tai Long Wan -- Tales from a vanishing village Introduction |

|

Tea money |

|

Forbidden fruit |

|

No sugar |

|

Treasure in a bowl of porridge |

|

Hong Kong and Southeast Asia -- Journalist follows his nose |

| Nutrient Starved Soils Lead To Nutrient Starved People |

|

Cecil Rajendra A Third World Poet and His Works |

|

Leave the farmers alone Book review of "Indigenous Agricultural Revolution -- Ecology and Food Production in West Africa", by Paul Richards |

|

A timeless art Some of the finest objects ever made |

|

Health hazards dog progress in electronics sector The dark side of electronics -- what happens to the health of workers on the production line |

|

Mo man tai ('No problem') -- "Write whatever you like" -- a weekly column in Hong Kong Life magazine Oct. 1994-Jan. 1996 |

|

Swag bag Death of a Toyota |

|

Curriculum Vitae |

|

|

Johannesburg, 1974

Jake's face flickered in the flames of the log fire, his tenor saxophone flashed red-gold as he worked the keys.

___His profile made a black hole against the candlelight washing off the wall behind him. His neck craned out to the sax, his throat a straight line from his tie knot to the tip of his chin, curling up to his lips over the mouthpiece. A speck of firelight danced in his eye.

Midori and Jake in Soweto, 1997 -- friends for life. |

___Jake's playing was liquid -- ripples and waves with crests curling over high notes and splashing down again, ebbing and flowing.

___He muffed a note, spluttered and stopped, indignant. "That was a brand new reed!"

___He laid down the sax, stood up and moved to the sax case on the floor nearby. Stooping, he opened it, took out a small bottle of lubricating oil for the keys, a neck strap, three library books on astronomy, an Instamatic camera, part of a telescope stand, a witchdoctor's love potion (pink powder wrapped in newspaper), a design for an antigravity machine sketched in pencil on a postcard, sheet music, odd photographs, some papers and forms, and a cigarette packet containing five broken mouthpiece reeds -- but no new reeds.

___"Jeewiz!" Irritated, he threw packet and reeds into the fire and watched them burn.

___"Here, Jake." I passed him the bottle of illicit wine we'd bought from the old black witch who ran a shebeen in her shack across the veld. He took the bottle and raised it to his lips for a long draught. He turned to the firelight and started reading the week-old newspaper page the bottle had been wrapped in.

___He found two stories that interested him. The first concerned the death of a Zionist Christian Church bishop, Joseph Lekganyane, prophet messiah to millions of devout blacks, and Jake's brother-in-law, in a complicated sort of way. The second was about a white Eastern Transvaal farmer named Eliastam who it was reported had built a school for the children of his black labourers. Jake showed it to me, I read it and looked at the photograph, and then he told me a tale about the philanthropic Mr. Eliastam. He said:

It was a winter morning at home in Dark City -- Alexandra Township. We had only one room there: bedroom, kitchen, lounge -- everything in one room. We were asleep -- it was very early in the morning. Then the police came -- pass raid! Black cops, black like us -- they didn't even knock politely, they just came and kicked the door in. And they didn't ask questions, ai, man, they beat us with their sticks instead.

___I tried to run away -- I was screaming, Jeewiz -- but they took us away, me and my brother Elias. I told them I was a recording artist: the record company gave us papers for the police, saying: To Whom It May Concern -- phone us immediately if there is any difficulty concerning myself, the bearer. The police didn't care about the paper, they just tore it up.

___My mother, she tried by all her means to help us. That morning she went to the Wynberg Court, where we were. She wanted to pay for us, I and Elias. But they said no. There was no fine.

___The offence? The offence was failing to produce a pass. I couldn't get a pass. I was young at the time, they wouldn't give me one. I went to the pass office three times with my mother, but I was too young for a pass, they said, so they wouldn't give me one. Then they arrest me for not having one.

___And Elias -- well, he's my elder brother, but I must say that he was just an ignorant somebody-or-other. He didn't have time for the pass office -- he didn't like to think about standing in the long queue there. He'd rather go and wear nice clothes, walking round the streets for all the girls to see him, walking along playing a pennywhistle for the dolls. He had plenty of girls, that boy -- even now, that guy's got girls all over... But he didn't have a pass.

___At the court afterwards they sold us. Like at an auction -- money for labour. They sold us to Mr. Eliastam. He bought a lot of us there that day -- thirty, maybe. They put us all in a big lorry, an open truck, guarded by people with spears.

___I remember somebody tried to escape. He jumped off the lorry into the road and he fell -- he tried to dodge, but the lorry was speeding. He timed wrong and he fell. I saw him shaking and writhing on the ground, and I thought he was dying, sure, he was dying. Nobody knows what happened to him. They just left him there. If they stop the truck everybody's going to get off and run away from them, so they just left him there to die in the road.

___Now the guards begin to be very aggressive. Those guys with their spears, looking at us with warning eyes, very mean eyes... We'll spear you -- they were thinking about it, thinking about doing it to us.

___In the end we came to this farm, well guarded with gates and a big fence, and deep inside the farm a huge garage, like an aeroplane shed, with big doors.

___They pushed us inside the garage: three of them this side, three that side, they push the doors closed, locking the outside.

___Man, it's a July night, the middle of winter -- it's cold. But they start to strip us, take off our clothing, trousers too, and they give us sacks -- one sack to wear, one sack to sleep on. No blankets, you just take this sack and you sleep right on the cement floor, and there are big gaping holes in the roof. It's cold, the wind gets in, everything gets in. So we sort of sleep, in the sacks on the cement.

___And at four o'clock in the morning -- sticks! Wake up! Wake up and work! Wake up! Wake up and work! Four o'clock! We're like beasts in our sacks -- others haven't even got shoes. They gave me shoes, but bi-i-ig ones, army boots -- much too big. And a can, not even a flask.

___They take us in a tractor, far -- two hours in the tractor. Six o'clock, cold, no food, we work, loading mealie corn, and it's so hard, it's so cold. Icicles on the mealie corn, and what about your fingers? No gloves.

___And I'm a slow man. It's in everything I do. I can't hurry -- if I try to make things faster then I just mess it up. So they chase me -- dragging a 190-pound bag, dragging it and carrying it to the tractor. After filling it up. You have to be fast about it, otherwise you get it -- you get a very big stick right in the middle of your back.

___Every day work -- Saturday, Sunday too. Such a place: work, bad food, no clothes, terrible cold, no sleep. After three weeks I couldn't take it anymore. We form a scheme, I and my brother. We are going to run away.

___I start to climb -- this big door has bars, sort of girders. I go up -- I'm a cat. I went right to the top. I start to walk, to move by the roof poles, one by one, until I reach the window. Slowly, quietly, I break the glass, and I come down again. And then I made a mistake -- I fell asleep.

___We were very tired. Waiting for the right time, I fell asleep, and Elias too. And then these guys climbed up there and jumped out -- they didn't know what was underneath, they just jumped. There were some chickens there, they landed on top of them -- qwak qwaak qwaak! And the dogs started, wow wow! The guards chased after them, but they were too late to catch them, they ran away -- seven or eight of them.

___The guards came back, opened up the big doors. They were like madmen -- the farmer was there, he was worse than them. They beat us with whips, but everybody kept quiet, nobody said anything.

___They beat us more, and then this Venda guy, he told them everything, he said he saw me climb. And then the farmer, this Eliastam, he tried to kill me -- he hit me, kicked me, tried to drop me down, but he couldn't. He tried and he tried, but I still stood up.

___He called one of the guards, they put handcuffs on my hands, behind my back. He beat me again -- I lost my balance with the handcuffs, I fell to the ground. Then he was on top of me, on the ground, his hands on my throat, choking me -- he's shouting all the time, I must tell him the truth, he wants the truth, where are they, the labourers who ran away, what about his crops, where are they? Ai, man, he hit me that guy, he choked me, kicked me on the ground there, right into another dimension for the whole night.

___I lay there all night, and everybody thought I was dead. Because there was no heartbeat in me -- but my brains were still working: only the heartbeat was so soft it wasn't there.

___I was not unconscious because I sort of saw myself, sort of dreaming myself, I think. It was just like a dream: I was seeing myself in it. I don't know for how many hours, but I was still there the following morning, lying there dead, handcuffed on the cement... until something brought me back, just when the sun was rising.

___I could feel myself again, I heard that farmer saying: Ja, nou is hy reg -- Yes, now he's alright. I saw people coming to me, many people. My brother, I saw he was angry. He told me afterwards they wanted to bury me there on the farm, and he was fighting them, he told them: I will take my brother home, it is my brother -- otherwise kill me too -- you will never bury him in a field...

___They asked me my name -- but I couldn't answer them, I didn't know my name. I didn't know myself... Then I remembered: My name is Jake. Then they took my hands, took the handcuffs off me -- still the handcuffs, on the cement! And they left me alone that day.

___That farmer, the same day that he killed me, he got a letter from my mother's lawyer, Mr. Joel Carlson. They were so afraid of him at Wynberg Courts, that man, and so was the farmer. They started to treat me nicely. They didn't want me to work anymore. They let Elias and me out of that aeroplane garage then. We left the prisoners, we went to live in the compound with the paid workers -- a taste of freedom, good food, warm, our clothes back, getting water when we wanted to wash... The rest of the prisoners stayed in the garage, including that Venda. But we lived good for a whole month. Then I went home.

___But that man Eliastam, when he beat me, he did something to my throat, my voice -- he made my voice like this when he strangled me. It was already deep, but not like this -- so deep, growlly, hor-hor. I thought he broke it, but no, my voice is famous -- all over they know me: Jake, the man from the stars with the big voice. They know my songs... and now, all the bands have groaners who try to copy my voice, but they can't -- it wasn't them who died that day, it was me, and there were no groaners before then.'

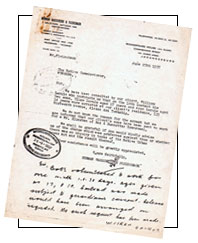

Jake had kept the letter lawyer Carlson (later famous for his courageous enquiries into the deaths of political prisoners killed in police detention) had written to the "Native Commissioner" at Wynberg.

Herman Wasserzug and Fleischak

Herman Wasserzug and Fleischak

Shakespeare House

Commissioner Street

JOHANNESBURG

June 25th 1957

The Native Commissioner,

WYNBERG.

Sir,

___We have been consulted by our client, William Lerula who instructs us that on the 14th instant his sons, Elias Lerula aged 17 years and Jacob Lerula aged 14 years were arrested at our client's residence, 123 Sixteenth Avenue, Alexandria Township.

___We do not know the reason for the arrest but we are informed that our client's sons have been sent to work for a Mr. Eliastam of Box 6 Dunnottar Transvaal.

___We shall be grateful if you would kindly advise us of the charge which was preferred against them or whether there was in inquiry in terms of the Native Urban Areas Act and the result thereof.

Yours faithfully,

Herman Wasserzug and Fleischak.

Joel Carlson

[Signed]

The letter was rubber stamped by the Native Commissioner, Alexandra Township, P.O. Box Bergvlei, 25-6-1957, and at the bottom was scrawled the magistrate's reply:

Sir,

___Both volunteered to work for one month i.e. 30 days. Ages given as 17 and 19. Contract was made subject to guardian's consent. Release would have been arranged on request. No such request has been made.

Wilken 40-1247"

... "E Bra Keith..."

___"I thought you'd fallen asleep, Jake."

___"No, I am awake now," he yawned. "That story reminds me -- can you fix my pass?"

___"What's wrong with it?"

___"No, nothing's wrong with it -- it just needs you to sign it, asseblief baas (please boss)."

___"Baas? What do you mean, baas?"

___He laughed: "It is true, you are my baas."

___My music promotion business paid Jake a retainer of R200 a month -- not too much but all I could squeeze out of the accountant, and Jake didn't have to do anything for it. Which made me his white boss. Your white boss has to sign your pass every month otherwise you lose your "right" to be in an urban area and are "endorsed out" to the tribal lands -- even if you were born in the city and had no idea which tribe you came from. This is one of the great evils of racist South Africa.

___"Give it here then. Have you got a pen?"

___"Yes." He took a pen from his jacket and a wallet from his back pocket. He opened the wallet, removed the pass book, opened it and handed it to me with the pen. I looked at it.

___"Whose signature is this for last month?"

___"That's Louis Peterson, at the record company."

___"But Louis can't sign your pass, he's a black."

___"No, he's a Cape Coloured."

___"Oh, so he is." Mixed-race Cape Coloureds (and Asians) are "second-class citizens", blacks are only "third-class citizens". I suppose it all made some sort of insane sense to somebody or other, but it never made any sense to me.